Scoliosis in Children and Teenagers: An Overview

Scoliosis: A parent's concern

Avoiding scoliosis and maintaining good posture are universal concerns among patients and parents today. Many patients and their families may be surprised to know that small curves are a normal part of spine anatomy.

Like many aspects of growth in young children, healthy development of the spine can vary slightly from child to child with small curves constituting a normal part of spine anatomy. But if curves are observed by a parent, teacher, school nurse, or physician, the child should receive a an evaluation by a specialist for early onset scoliosis.

Children and adolescents who are noted to have any curvature in their spines require medical attention. These children may be diagnosed with scoliosis – a sideways curvature of the spine that may affect in any one or a combination of its three major sections:

- cervical spine (neck)

- thoracic spine (chest and upper back region)

- lumbar spine (lower back)

Scoliosis, together with kyphosis (a forward-oriented, rather than sideways curvature), composes a majority spinal deformity cases seen and treated by pediatric orthopedists.

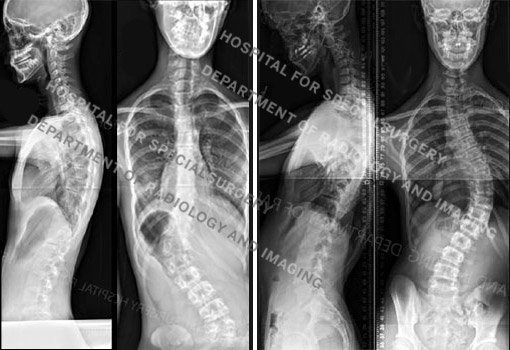

Figure 1. Posteroanterior (back-to-front) X-ray showing curvature of the spine in a patient with scoliosis

Forms of scoliosis in children and teenagers

Pediatric scoliosis is diagnosed as one of several types:

- Idiopathic scoliosis is a curvature of unknown origin.

- Congenital scoliosis is present at birth. A congenital scoliosis curve is where bones are asymmetrical at birth and the spinal vertebrae may be partially formed (hemivertebra) or wedge-shaped.

- Neuromuscular scoliosis is caused by an underlying systemic condition such as cerebral palsy, muscular dystrophy, spina bifida, spinal cord tumors, or paralysis.

- Syndromic scoliosis is a term for a unique group of spine conditions. Diseases such as Marfan’s Syndrome, Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome, osteogenesis imperfecta, neurofibromatosis, Prader-Willi Syndrome, arthrogryposis, and Riley-Day Syndrome are some of the common syndromic causes of this type of scoliosis.

Idiopathic scoliosis – the most common form of the condition – may first be recognized during a routine pediatrician’s visit or in a school screening. “School screenings are an important safeguard for many children, especially for children who may not have a regular healthcare provider,” notes John Blanco, MD, Associate Attending Orthopedic Surgeon at HSS. While children with idiopathic scoliosis usually do not experience pain, parents and caregivers may see cosmetic signs of the condition, such as a shoulder or hip that appears higher than the other or asymmetry of the rib cage. Cases can develop during infancy, childhood or adolescence, and patients who have idiopathic scoliosis are subcategorized by the age of the child when the condition is diagnosed:

- infantile idiopathic scoliosis − from birth to three years

- juvenile idiopathic scoliosis − from three to nine years

- adolescent idiopathic scoliosis − from 10 to 18 years

Adolescent idiopathic scoliosis is seen more frequently in girls than in boys. Although it is thought to be genetic, its true cause is unknown and thought to be a combination of many factors. It is characterized by a curvature of the spine measuring greater than 10 degrees (10°), has no other symptoms, and rarely causes pain.

Diagnosing scoliosis

The primary goal for a patient with any form of scoliosis is to get an early diagnosis. Treatment is guided by the specific scoliosis type, the amount of growth the child has left, the degree of the spinal curve, and anticipated progression of the condition. “Children with infantile and juvenile scoliosis have the greatest risk of curve progression, as well as the greatest risk of developing secondary pulmonary complications from scoliosis,” explains Roger F. Widmann, MD, Chief of Pediatric Orthopedic Surgery at HSS.

Pediatric orthopedists use physical examination and X-rays to diagnose early onset scoliosis. An initial X-ray is taken to determine the magnitude, location, and direction of the curve. Based on that X-ray, a determination is made regarding the type of scoliosis present, as well as its possible cause, and a treatment strategy is instituted.

At HSS, in children younger than 10 years of age, an MRI of the entire spine is often recommended to ensure that there are no other problems affecting the spinal cord. Children with congenital scoliosis should be assessed for the presence of any cardiac or kidney problems associated with their condition.

Children with suspected idiopathic scoliosis should see a pediatric orthopedist who can confirm the diagnosis with a physical examination and X-rays. A diagnosis of scoliosis is given when a sideways spinal curve as detected on an X-ray is greater than 10°. At HSS, in children younger than 10 years of age, an MRI of the entire spine is recommended.

Figure 2a and 2b. Posteroanterior (back-to-front) X-rays of idiopathic scoliosis. At left are images of a 14-year-old girl with a left thoracolumbar curve measuring 47° and a right lumbar curve measuring 20°. At right, are images of a 15-year-old boy with a long thoracic curve measuring 60°.

“In some cases, even though the vertebral bones may be healthy, the spinal cord may not be,” says Dr. Blanco. MRI images can help the orthopedist detect the presence of other problems such as syrinx (a cyst in the spinal cord) or tethered cord (when the spinal cord is abnormally attached to the bony portions of the spine).

Congenital scoliosis

Children with congenital scoliosis should also be assessed for the presence of any cardiac or kidney problems associated with their condition.

Neuromuscular scoliosis

This condition is rarely diagnosed at birth, since it is an acquired form of scoliosis, in which the development and progression of the scoliosis often is dependent upon the severity of the underlying medical condition, such as cerebral palsy. (Learn more about neuromuscular scoliosis.)

Syndromic scoliosis

Children with syndromic scoliosis often have curves in the spine early in life. As children with this condition grow, the curvature can progress and worsen. It’s important for a pediatric orthopedic surgeon to monitor the condition closely, because in some cases the curvature may eventually need to be treated.

Patients with this condition should also be evaluated by a geneticist and neurologist to determine which underlying condition could be the cause of the spine curvature. Sometimes these patients may have respiratory and cardiac conditions, related to the syndrome or secondary to severe spinal curvatures. Due to this risk, it is also important for these patients to be evaluated by a pediatric pulmonologist and cardiologist.

Treating scoliosis in the growing child

Treatment decisions must consider the age of the patient, the type of scoliosis, the size of the deformity, and the anticipated progression of the curve. “The period from birth to five years is crucial, because it is during this time that the lungs grow dramatically,” explains Dr. Blanco. If the chest cavity is constricted owing to scoliosis or other spinal deformities, lung growth can be significantly restricted and serious pulmonary complications may develop.

Based on all the information available, the pediatric orthopedist may recommend one or more nonsurgical or surgical treatments. (Find the best scoliosis doctor at HSS for you or your child based on age, condition, location and insurance.)

Nonsurgical treatments for scoliosis

Observation

For patients with smaller curves, those greater than 10° and up to 20°, the pediatric orthopedist may recommend careful monitoring of the condition with physical examinations and follow-up X-rays or EOS low-dose radiation images taken at three- to four-month intervals. If the curve progresses, additional treatment measures are introduced.

Bracing

For curves in the range of 20° to 40°, bracing can be an effective means of controlling some forms of early onset scoliosis, such as idiopathic scoliosis and some syndromic forms of the condition. (However, bracing is not appropriate for neuromuscular or congenital scoliosis.) Moreover, it must be emphasized that bracing does not correct the curve. Bracing is intended to prevent progression.

Casting: The Risser cast

A renewed interest in casting for early onset scoliosis has occurred. Casting can produce good results in children with infantile idiopathic scoliosis and those with syndromic scoliosis. Popularized recently by British physician Dr. Min Mehta, the technique employs a series of body casts to correct the curve called the Risser cast. Extending from just under the arm pit − some also have “straps” that go over the shoulders − to the curve of the waist area, Risser casts remain on the patient for two to three months at a time, based on the age of the child. The cast is then changed to increase the amount of correction.

“The theory behind the technique is that by keeping the child in the cast around the clock, you actually help the spine start growing in a more normal way,” says Dr. Blanco. This process continues for several months to years, sometimes with a two- or three-day interval between castings to allow the patient to bathe and to address any skin problems that may develop.

Because the cast always remains on except for these brief breaks, the technique offers an advantage over braces which are removed for bathing and changing clothes. Braces can be effective in arresting progression of a curve but cannot correct it. With casting, in certain patients, complete correction of the deformity is possible.” he adds. Presently, casting for the treatment of scoliosis is only available at a few centers in the United States.

The prognosis for patients with early onset scoliosis has improved significantly over the last 10 years, according to Dr. Blanco. When considering where to seek treatment, it’s important to look for an institution where a high volume of procedures is performed, there is a good medical support team in place, and the anesthesiology staff have experience working with patients with early onset scoliosis.

Surgical correction of scoliosis

Children with more advanced scoliosis (those with a curve of 45° or more) and that are progressing despite non-operative treatment are in danger of developing cardiac and/or respiratory problems may be candidates for surgical intervention. Although 2% to 3% of the adolescent population is diagnosed with adolescent idiopathic scoliosis, less than 10% of these patients require any surgical intervention.

The types of scoliosis surgery performed is usually one of two types:

- the placement of growing rods

- spinal fusion surgery

“In younger patients with significant growth remaining, magnetic growing rods may be preferable,” says Dr. Blanco. In this procedure, two adjustable rods are anchored to the spine to hold it in proper alignment. As the child grows, the rods can be adjusted in length simply by placing a magnetic device near the spine during an office visit. “Growing rods are also effective in that the child’s lungs and chest cavity can continue to grow along with the spine. Additionally, spinal fusion can be delayed until the child is significantly older,” says Dr. Widmann.

Growing rod technique

Growing rods (MAGec rods) are expandable devices that are attached to the top and base of the spine using screws or hooks. Every six months the orthopedic surgeon lengthens the rod by about one centimeter, which is the amount of growth expected in the spines of young children.

While the initial surgery to attach the growing rods lasts two or more hours, subsequent adjustments are brief procedures involving only a small incision and, in otherwise healthy children, may not require an overnight stay in the hospital. When the device has reached its full extension, the child may require another surgery to introduce a new longer set of growing rods.

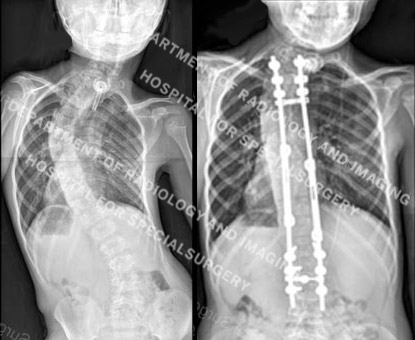

Figure 3. Posteroanterior (back-to-front) X-ray images showing a spinal curve in excess of 40° and then the same patient undergoing treatment with growing rods.

Spinal fusion surgery

Fusion, the traditional scoliosis surgery, usually is reserved for older children. In this surgery, two or more vertebrae are fused together with bone grafts and internal devices, such as metal rods, to stabilize the spine or correct a deformity. Sophisticated fusion techniques and new instrumentation to surgically correct progressive curves, enhances the recovery of patients. Such techniques include new endoscopic procedures that allow specialists to access the spine through the chest cavity, and perform the fusion with three or four small incisions.

Computer navigation is utilized to optimize safe placement of the rods, screws and bone graft to facilitate alignment and fusion of the spine. To decrease the risk of neurologic injury, HSS pediatric orthopedists use sophisticated nerve monitoring throughout the surgery. “This monitoring provides us with instant feedback, allowing the surgical team to adjust the deformity correction as needed or, if need be, change the implants,” explains Dr. Blanco.

“Surgery generally results in both excellent correction of the curve and improvement in spinal alignment,” says Dr. Widmann. Left untreated, a curve that continues to progress can eventually have a negative impact on both heart and lung function. Moreover, according to Dr. Blanco, at later stages, surgeries are both lengthier and tend to have a less satisfactory cosmetic result.

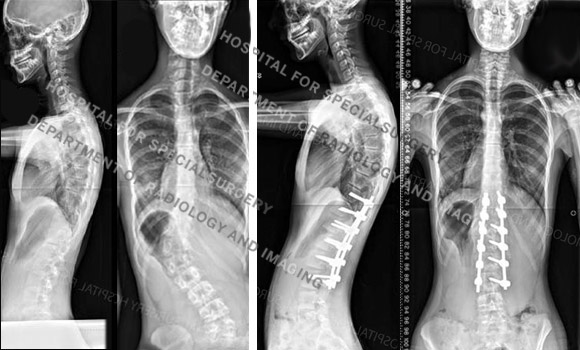

Figure 4. Posteroanterior (back-to-front) Before and after X-rays of the girl in Figure 2a, showing her original spinal curve and correction after fusion surgery.

Mature patients with curves less than 45° are not candidates for spinal fusion surgery since many of these curves will progress slowly or not at all during adult life. Curves measuring greater than 50° are generally managed surgically, since these curves may progress up to one degree per year after maturity is reached. This can present problems for the patient later in adult life.

Recovery from scoliosis surgery

Scoliosis surgery generally involves a four day hospital stay, and most children are back to school within three to four weeks. Young athletes are usually back to competitive athletics in four to six months following surgery.

Adolescent idiopathic scoliosis and young athletes

Adolescent idiopathic scoliosis is usually a painless condition, and it is common for affected patients to be athletic and participate in physical activities alongside their unaffected peers. If surgery is required, one common concern is the child’s ability to return to sports activity afterward.

After evaluating a group of 42 patients who underwent curve correction and spinal fusion at HSS over an average of 5.5 years after surgery, most (60%) had returned to sports at an equal or higher degree of physical activity. Postoperative athletic participation included a wide variety of sports. These ranged in vigor from recreational clubs to collegiate varsity teams. The only variable studied that correlated with a patient’s return to activity to the same or greater intensity after surgery was the lowest level of spinal fusion. This was determined by the size and extent of the spinal curvature.

While patients are typically allowed to return to sports 6 to 12 months after surgery, this study indicated that the lowest level of fusion might predict the patient’s actual likelihood of returning to play at or above the preoperative level. Further ongoing research at HSS will elucidate why this is the case, but the data collected here may help guide patient and family expectations regarding return to athletic activity.

Looking to the future

According to Shevaun Mackie Doyle, MD, Associate Attending Orthopedic Surgeon at HSS, the future of scoliosis treatment is promising. “Numerous interesting research initiatives are underway to improve our spine instrumentation for children and teenagers with scoliosis,” she says. “In addition, non-ionizing diagnostic studies may be available in a few years that will help us predict which children will progress to have severe deformities and which ones will not.”

Updated: 3/1/2024

Authors

Attending Orthopedic Surgeon, Hospital for Special Surgery

Associate Professor of Clinical Orthopedic Surgery, Weill Cornell Medical College

Attending Orthopedic Surgeon, Hospital for Special Surgery

Associate Professor of Orthopedic Surgery, Weill Cornell Medical College

Attending Orthopedic Surgeon, Hospital for Special Surgery

Instructor in Orthopedic Surgery, Weill Cornell Medical College

Attending Orthopedic Surgeon, Hospital for Special Surgery

Professor of Clinical Orthopedic Surgery, Weill Cornell Medical College