Neuromuscular Scoliosis: Complex Spinal Curves Caused by Muscular and Neurological Conditions

There are four main types of scoliosis found in children and adolescents: idiopathic scoliosis, congenital scoliosis, neuromuscular scoliosis and syndromic scoliosis. Idiopathic scoliosis, the most common form, has no underlying identifiable cause. Congenital scoliosis is scoliosis due to underlying defects in the vertebrae, causing a curvature in the spine. Syndromic scoliosis is a type of scoliosis that is associated with another condition, such as Marfan Syndrome, Down Syndrome, or Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome. Neuromuscular scoliosis is a direct consequence of an underlying muscular or neurological condition, such as cerebral palsy, muscular dystrophy or spina bifida.

What is neuromuscular scoliosis?

Scoliosis is defined as a curvature in the spine that is greater than 10 degrees. Neuromuscular scoliosis is a form of scoliosis (a sideways curvature of the spine) that results from a lack of muscular control or spasticity of the muscles caused by a neurological or degenerative muscular condition, such as cerebral palsy or muscular dystrophy.

Neuromuscular scoliosis represents only a small segment of the total number of scoliosis cases diagnosed each year. However, the underlying disorders associated with this form of scoliosis often result in some of the more complex and extensive curves seen by pediatric orthopedic surgeons and present a unique set of treatment challenges.

What causes neuromuscular scoliosis?

Neuromuscular scoliosis is caused by muscle weakness, paralysis or neurological issues related to an underlying condition, including:

- cerebral palsy

- muscular dystrophy

- paralysis

- spina bifida

- polio

- benign or malignant musculoskeletal tumors, such as soft-tissue sarcoma

What are the symptoms of neuromuscular scoliosis?

As with idiopathic scoliosis, neuromuscular scoliosis is diagnosed when there is the presence of a curve in the spine that measures greater than 10 degrees. In contrast to patients with idiopathic scoliosis, in which the curve pattern is restricted to smaller segments of the spine [see Figure 1], children with neuromuscular scoliosis develop long, sweeping S- and/or C-shaped curves that involve the entire spine, including the sacrum (the vertebrae that form part of the pelvis) [see Figure 2]. The curves seen in children with neuromuscular scoliosis are also much more likely to progress than those seen in idiopathic scoliosis.

Children with neuromuscular scoliosis continue to be at risk for progression of their deformities into adulthood. Children who have idiopathic scoliosis with curves that are less than 45 degrees generally do not have continued curvature progression once they reach their adult height.

Figure 1: Posteroanterior (back-to-front) view X-ray of a patient with idiopathic scoliosis

Figure 2: Posteroanterior (back-to-front) view X-ray of a patient with neuromuscular scoliosis

How is neuromuscular scoliosis diagnosed?

As with other forms of scoliosis, X-rays of the spine are key tools in the diagnosis of neuromuscular scoliosis. Often, these patients are unable to stand, so they have these radiographic images taken in a seated position.

How is neuromuscular scoliosis treated?

Wearing a special brace, and other nonsurgical treatments may help some patients with balance or seating difficulties, but only spinal fusion surgery will stop the progression of the curvature in the spine. (Find a doctor at HSS who treats scoliosis.)

Non-operative management

For some patients, braces may be recommended to help achieve sitting balance, thereby freeing the arms for other activities. Custom seating systems can also help accomplish this goal. However, unlike in idiopathic scoliosis where bracing can help prevent progression of curves, bracing is only used for comfort or functional aid in neuromuscular scoliosis. It is important to understand that bracing treatment will not slow the progression of the curve as it can in some other forms of scoliosis.

Surgical treatment

Surgical treatment of neuromuscular scoliosis is performed to stop the progression and correct the curve. As a patient’s pelvis is brought back to a more level position, it provides a stable platform for sitting.

The pediatric orthopedic surgeon will place screws, rods, and bone graft along the vertebral column to straighten, fuse, and maintain the spinal curve correction. Computer navigation assistance facilitates enhanced accuracy when placing the screws. For these patients, we almost always use allografts (freeze-dried, irradiated donor bone) with excellent results. Patients with neuromuscular scoliosis often have poor bone density, therefore, a variety of techniques are used to fix the rod in place, including hooks, pedicle screws, and wires.

Timing of the surgery varies and may be dictated by the underlying disorder. In the presence of muscular dystrophy, for example, we consider surgical intervention once the child is wheelchair-bound, since curve progression seems to be related to loss of ambulatory ability.

A curve less than 40 degrees may also require surgery in patients with muscular dystrophy since the curve is expected to progress in a predictable manner. In the presence of cerebral palsy, surgery may not be recommended until there is documented progression of the curve to 45 or 50 degrees and/or the child develops difficulty sitting or maintaining his/her balance.

Children who are surgical candidates must be screened carefully. At HSS, our multidisciplinary team of health care professionals ensures that children have optimal breathing function. Safeguards are in place to prevent pneumonia and any potential difficulties with swallowing − risks that may be associated with the underlying disorder. All patients with neuromuscular scoliosis undergo a preoperative evaluation from our pediatric team. Our pediatricians determine whether patients need to see other specialties for optimization/clearance prior to surgery, such as neurology, pulmonology, or cardiology.

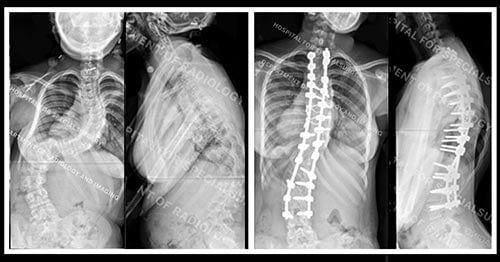

Figures 3 and 4: Posteroanterior (back-to-front) and lateral (side) view X-rays of a patient with neuromuscular scoliosis

Figures 5 and 6: Posteroanterior (back-to-front) view and lateral (side) views of the same patient after surgery

What are the risks of surgery for neuromuscular scoliosis?

Patients with neuromuscular scoliosis have an increased risk of blood loss during surgery. Multiple precautions are taken to address this, including the use of a cell saver (a machine that filters the blood so that it may be given back to the patient), if needed. Patients with neuromuscular scoliosis are also at an elevated risk for infection. Additionally, they may require continued breathing support after surgery for a day or two.

What is the recovery like?

Following surgery (usually one to two days), many children with neuromuscular scoliosis remain in the pediatric intensive care for acute respiratory management. In most cases, one surgery is performed for correction of the curve, although some patients with very large curves may require a second procedure for additional releases and fusions.

Learn more about the Pediatric Orthopedic Service at HSS, or find a doctor at HSS to treat your scoliosis, based on your age, specific condition, location and insurance.)