ACL Tear (Torn ACL)

Summary: This article provides a comprehensive overview of anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) tears, a common knee injury among athletes and active people. It describes the typical symptoms and discusses associated injuries such as damage to the meniscus or MCL. It outlines nonsurgical and surgical treatment options along with special considerations for children, women, and athletes, as well as long-term outcomes and risks, including knee arthritis, for people with severe tears who opt not to have surgery.

On this page:

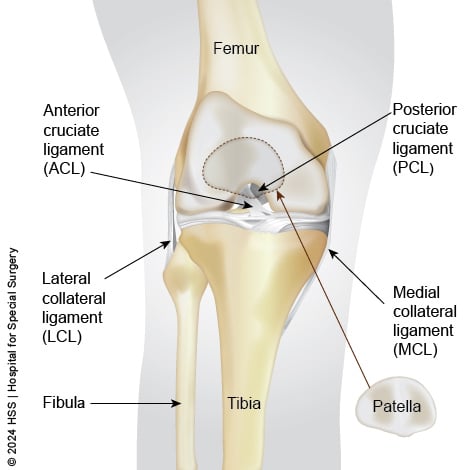

What is the ACL?

The anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) is one of four major ligaments in the knee joint. It helps maintain the knee's rotational stability and prevents the tibia (shin bone) from slipping in front of the femur (thigh bone). The ACL is located in the center of the knee and works with the posterior cruciate ligament (PCL) to stabilize the front-to-back movement of the knee.

The ACL prevents excessive forward movement of the tibia and the PCL prevents excessive backward movement of the tibia.

The medial collateral ligament (MCL) and lateral collateral ligament (LCL) are located along the outside (LCL) and inside (MCL) of your knee. The MCL and LCL work in preventing the tibia from moving to the inside (MCL) or outside (LCL).

The ACL is particularly vulnerable to injury during pivoting or side-to-side athletic activity or as the result of impact. A torn ACL is a common injury in athletes of all levels. It is especially common in sports with a lot of leg planting, cutting and pivoting, such as soccer, basketball, skiing, and football. ACL surgery is often required to treat a tear.

What is an ACL tear?

An ACL tear is when the anterior cruciate ligament becomes partially or completely ruptured. Most ACL tears are complete tears and can be torn from the femur (thighbone), tibia (shin bone), or in the center of the ligament. The most common location for a tear is the center of the ligament.

Ask the Expert: Dr. Riley J. Williams III on ACL tears

ACL Tears Explained: Causes, Treatment & Recovery

What is the difference between an ACL sprain and an ACL tear?

An ACL tear is a complete tear, or rupture, of the ligament. An ACL sprain is a stretch to the ligament, but the fibers of the ligament remain intact. Can an ACL tear heal on its own?

Once torn, an ACL cannot regrow or heal on its own. Surgery is the only way to treat an ACL tear. Not everyone who has torn their ACL, however, necessarily needs surgery. On some occasions, the ACL can form a scar that bridges the gap between the ligament’s torn ends leading to some restoration of knee stability, allowing patients to return to activities symptom-free. This treatment option is generally reserved for older patients.

What is a partial ACL tear versus a complete ACL tear?

In a partially torn ACL, only some of the fibers that compose the ligament are damaged or ruptured, while some remain intact. In a complete ACL rupture, the all the ligament fibers are torn through.

Side-view MRI showing a healthy, intact ACL.

Side-view MRI showing a completely torn ACL.

Who tears their ACL?

People of all ages, physical conditions, and abilities can tear an ACL. Active, young, females experience a higher incidence of ACL injuries than males of the same age because of a multitude of factors, including landing mechanics, anatomy of the knee joint, inherent looseness of tissues. Females are also at higher risk of ACL injury in the contralateral (opposite, uninjured) knee, in the future. Current research is focusing on developing strategies to prevent ACL injuries in all athletes and prevent future re-injury or new injuries as well.

ACL injuries are also common in children, especially as youth sports become increasingly competitive. Until recently, ACL treatment for children and adolescents was exclusively nonsurgical. This was because traditional ACL surgery techniques could cause growing children to develop a leg length discrepancy or growth deformity. However, newer surgical techniques have made surgical treatment an option for many kids and teens.

How do you tear your ACL?

A partial or complete ACL tear (rupture) often occurs during a sudden twisting movement, in which a person stops quickly and changes direction, especially while pivoting or landing after a jump. A sudden, high-energy impact to the knee can also cause the ACL to tear.

ACL tears can be accompanied by injuries to other tissues in the knee, including the meniscus, cartilage, and the other knee ligaments (MCL, PCL, LCL). The most common injury associated with an ACL tear is a meniscus tear). Either the medial (inside) or lateral (outside) meniscus can be torn with an ACL tear. Sprains or tears of the MCL can also be associated with an ACL tear and are common in patients who injure their ACL while skiing. (Learn more about combination ACL and MCL tears.) Doing specific exercises, especially as part of a guided injury prevention program, can reduce the chances of tearing your ACL.

ACL tears that occur in conjunction with multiple other ligament injuries are usually a result of a high-energy injury, such as a car accident.

What are the symptoms of an ACL tear?

Common symptoms of a torn ACL include a popping sound at the time of injury, knee pain, swelling and knee instability, especially during weight-bearing activity.

What happens when you tear your ACL?

When a person tears their ACL, they often report hearing a popping sound at the moment that the tear occurs. The knee will quickly swell and, in many cases, feel unstable. However, in some less severe tears, these symptoms may be mild. This is especially the case in people whose lifestyles do not involve intense physical activity.

A person with a partial ACL tear may have knee pain, swelling, and joint instability but the degree of all three may depend on the extent of the tear and the individual patient. If the ACL is completely torn, there will be instability in the knee that will cause feelings of sudden shifting or buckling. People will be unable to:

- jump and land on the knee

- accelerate and then change directions

- rapidly pivot on the knee

When should I see a doctor if I think I have torn my ACL?

If you sustain a knee injury and think you have injured your ACL, you should follow these steps:

- Stay off the leg and elevate it.

- Decrease the inflammation in the knee by:

- Applying ice.

- Taking nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) such as ibuprofen.

- Consult an orthopedist or sports medicine physician as soon as possible.

The doctor will examine your knee and take X-rays, and perhaps recommend an MRI to look for injuries to your ligaments, meniscus, or cartilage based on your exam and discussion with the doctor.

How is a torn ACL diagnosed?

A doctor can usually diagnose a torn ACL from a physical exam, although magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is helpful. The physical exam is a critical portion of your evaluation and will be performed during your doctor’s visit. Based on your exam, your doctor may recommend an MRI of your knee. An MRI can help determine if other injuries, such as to the cartilage or meniscus, have occurred.

Diagnosing partial versus complete ACL tears

To determine whether a tear is partial or complete, a doctor will perform several manual tests and order an MRI. Tests include:

- Lachman test: The physician will try to pull the shin bone away from the thigh bone. If the ACL is torn but still intact, the bones won’t move or will do so only slightly.

- Pivot shift test: The patient lies on their back while the doctor lifts their leg and places rotational pressure on the knee. If the bones don’t shift, the test is negative.

Can ACL tears be treated without surgery?

Surgery is not necessary for all patients. The main conservative treatments are rest and anti-inflammatory medication to reduce pain and inflammation, with physical therapy to help strengthen the muscles of your leg. In patients who have only a partial tear, nonsurgical treatment may be an option. Some patients who have a complete ACL tear do not require surgery and are able to return to activities, such as cycling or running with or without a brace. Your doctor will discuss all treatment options with you.

Possible disadvantages of nonsurgical treatments

The long-term outcome for patients who are treated nonsurgically varies. Those who return to unrestricted activity are likely to experience some knee instability with side to side or pivoting movements. In the absence of an intact ACL – even when no other injury is present – the menisci (pads of cartilage that cushion the bones that meet at the knee joint) have a higher risk of injury during twisting or pivoting activities. Most patients who participate in activities such as running or cycling, may be able to return without surgical intervention for the ACL injury.

When is surgery necessary?

The choice to have surgery is usually based on the patient's lifestyle. In athletes and other people of any age who wish to continue doing physically demanding activity, an ACL reconstruction surgery is often needed.

If the injury is not too severe, some patients who do not need to perform intense athletics or physical labor may be able to go without surgery and still lead active, healthy lifestyles. Many people with torn ACLs who receive conservative, nonsurgical treatments are able to swim, jog and use most equipment found at the gym or health club.

Without surgery, however, there is an increased risk of developing knee osteoarthritis. An HSS study of 40 surgical and nonsurgical patients over more than 10 years found that the long-term effects of an ACL tear without surgery includes damage to the surrounding cartilage, which worsens over time. MRIs taken between 7 and 11 years demonstrated that patients who did not have ACL reconstruction were six times more likely to have cartilage degeneration in the shinbone and five times more likely to have degeneration in the kneecap than those who did. Discuss all the risks and benefits of surgical and nonsurgical treatment with your doctor.

Key takeaways

- The anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) is crucial for stabilizing the knee during pivoting and side-to-side movements, making it especially vulnerable to injury in sports like soccer, basketball, skiing, and football.

- ACL tears are typically complete ligament ruptures and are often accompanied by a popping sound, swelling, pain and knee instability. Partial tears are less common but can still cause symptoms.

- Female athletes are at higher risk for ACL injuries due to anatomical and biomechanical factors and may also be more prone to future tears in the opposite knee.

- Diagnosis involves a physical exam and usually an MRI to determine whether the tear is partial or complete and to check for associated injuries like meniscus or MCL tears.

- ACL tears do not heal on their own. Surgery is often recommended for active people but some others, such as older adults or those with low physical demands, can be treated nonsurgically.

- Children and teenagers with ACL tears can now be considered for surgery using techniques that protect their open growth plates.

- Long-term studies show that untreated ACL tears can lead to cartilage degeneration and increased risk of knee osteoarthritis, even in the absence of other injuries.

Below, explore articles and other content on ACL injuries.

ACL Tear (Torn ACL) Success Stories

Medically reviewed by Shevaun Mackie Doyle, MD ; Peter D. Fabricant, MD, MPH ; Daniel W. Green, MD, MS, FAAP, FACS ; Michelle E. Kew, MD

References

- Albright JC, Carpenter JE, Graf BK, et al. Knee and leg: soft tissue trauma. In: Beaty JH, editor. Orthopaedic knowledge update 6. Rosemont (IL): American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons; 1999. p. 533.

- Musahl V, Karlsson J. Anterior cruciate ligament tear. N Engl J Med. 2019 Jun 13;380(24):2341–8.

- Cancienne JM, Browning R, Werner BC. Patient-related risk factors for contralateral anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) tear after ACL reconstruction: an analysis of 3707 primary ACL reconstructions. HSS J. 2020 Dec;16(Suppl 2):226–9. doi: 10.1007/s11420-019-09687-x. Epub 2019 May 30. PMID: 33380951; PMCID: PMC7749876.

- Devana SK, Solorzano C, Nwachukwu B Jones KJ. Disparities in ACL reconstruction: the influence of gender and race on incidence, treatment, and outcomes. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med. 2022 Feb;15(1):1–9. doi: 10.1007/s12178-021-09736-1. Epub 2021 Dec 31. PMID: 34970713; PMCID: PMC8804118.

- Forsythe B, Lu Y, Agarwalla A, Ezuma CO, Patel BH, Nwachukwu BU, Beletsky A, Chahla J, Kym CR, Yanke AB, Cole BJ, Bush-Joseph CA, Bach BR, Verma NN. Delaying ACL reconstruction beyond 6 months from injury impacts likelihood for clinically significant outcome improvement. Knee. 2021 Oct 30;33:290–7. doi: 10.1016/j.knee.2021.10.010. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 34739960.

- Gordon MD, Steiner ME. Anterior cruciate ligament injuries. In: Orthopaedic Knowledge Update Sports Medicine III, Garrick JG (Ed), American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons, Rosemont 2004. p.169.

- Halvorsen KC, Marx RG, Wolfe I, Taber C, Jivanelli B, Pearle AD, Ling DI. Higher Adherence to Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injury Prevention Programs Is Associated With Lower Injury Rates: A Meta-Analysis and Meta-Regression. HSS J. 2023 May;19(2):154-162. doi: 10.1177/15563316221140860. Epub 2022 Dec 13. PMID: 37065096; PMCID: PMC10090850.

- Potter HG, Jain SK, Ma Y, Black BR, Fung S, Lyman S. Cartilage injury after acute, isolated anterior cruciate ligament tear: immediate and longitudinal effect with clinical/MRI follow-up. Am J Sports Med. 2012 Feb;40(2):276-85. doi: 10.1177/0363546511423380. Epub 2011 Sep 27. PubMed PMID: 21952715.