Lumbar Spinal Stenosis

Low back pain is a common complaint. An estimated 70% to 85% of the adult population is reported to experience the problem at some point during their lifetime. While the source of back pain – including pain radiating down from the back into the buttocks and lower extremities – can be difficult to diagnose, there are a number of signs and symptoms that may indicate the presence of lumbar spinal stenosis.

What is lumbar spinal stenosis?

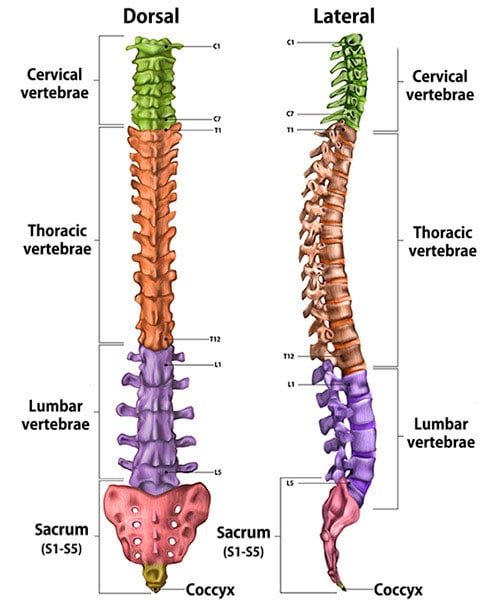

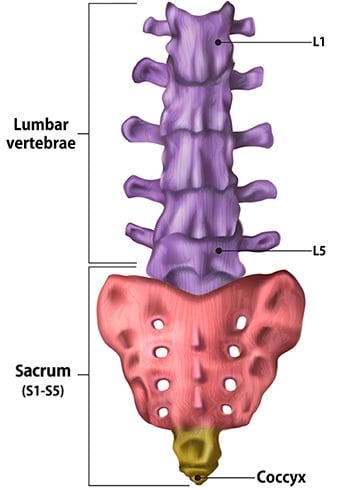

Spinal stenosis means a narrowing of the spinal canal – a space within the spine which protects the spinal cord and nerve roots. Lumbar refers to segment of your spine that contains the five spinal vertebrae (L1 to L5) of the lower back.

Illustration of cross-section of spine, dorsal (back to front) and lateral (side) views, showing its vertebral sections.

(Find a doctor at HSS who treats spinal stenosis.)

What are the symptoms of lumbar spinal stenosis?

In addition to low back pain, common symptoms generally include a sense of fatigue, discomfort, or changes in sensation (for example, numbness or tingling) felt in the buttocks, thighs, and legs on both sides of the body. This fatigue is made worse by walking or standing and is often relieved by sitting to rest. People often also complain of a decreased ability to walk long distances.

Viewed from the side, the spine appears as alternating layers of vertebrae (bones that form a ring-like structure) and discs (soft spongy structures that provide cushioning between the vertebrae and contribute to mobility). Together, the bony vertebrae and soft discs form both a stable column that enables us to stand upright, as well as a protective passageway through which the spinal cord and individual nerve roots pass from the brain to the base of the spine.

MRI (sagittal view) of a normal spine.

MRI (sagittal view) showing stenosis.

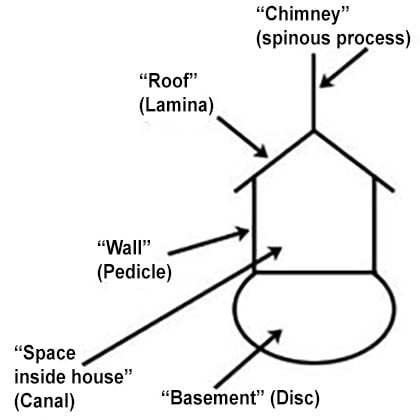

Viewed in cross-section, the complex anatomy of the bony spine and the spinal canal is clearer. This complex structure can be thought of as a house sitting on a foundation. In the diagram below, the bony spine is represented by the chimney, roof, and walls of the house connected at the foundation to the bony vertebral body. The spinal cord and nerve roots are protected within the walls of the house.

Diagram of "house" analogy.

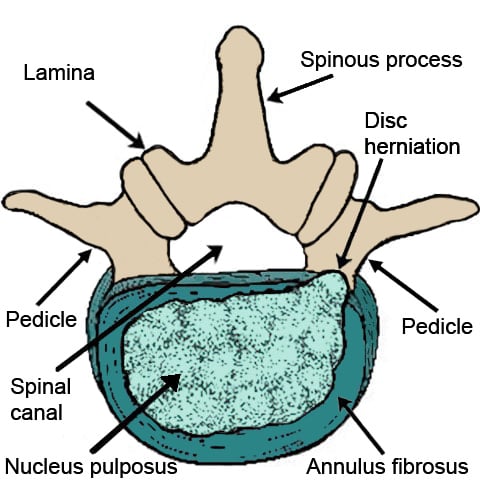

Illustration of lumbar spine vertebra showing a disc herniation.

What causes lumbar spinal stenosis?

Trauma to the spine can cause stenosis, but more commonly, narrowing within the lumbar spine is the result of normal wear-and-tear on the spine in the form of herniated disc, degenerative disc disease, and osteoarthritis of the spine (also known as spondylosis).

A herniated disc is where the rubbery cushions between vertebrae bulge out of place or rupture which can squeeze a spinal nerve. In the "house structure" analogy mentioned above, this is like a portion of the basement or foundation of the "house" moving upward, constricting the space above.

Arthritis of the spine causes swelling in the spinal joints and development of bony spurs (known as osteophytes) at the edges of the spine where the “roof" meets the “walls” (known as facet joints).

In addition to the bony structures described above, there are soft tissues present in the spine, including ligaments and fat. Inflammation and swelling of these tissues can also contribute to the problem.

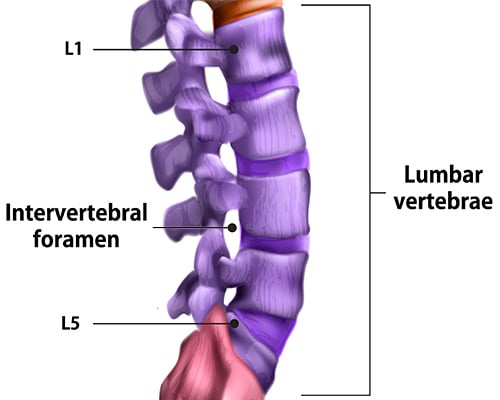

In addition to a narrowing in the central canal of the spine, people may have narrowing in the intervertebral foramen, an opening (much like a window in the "house" that has been described) through which nerve roots extend on either side of the spine. Finally, narrowing may occur in the lateral recess of the spine, a unique area within the canal directly beneath the facet joints. People with spinal stenosis may have any one or more affected areas which can cause different types of symptoms.

Illustration of an intervertebral foramen.

Spinal stenosis can also be a result of congenital process (congenital spinal stenosis – present at birth). In individuals with congenital stenosis, the vertebral pedicles or "walls" of the "house" are abnormally short beginning at birth and continuing through development. Because the “house” in these people is much smaller than that of the average person, even small changes to the spine can result in narrowing. Pain and other symptoms of this condition can occur earlier than others, sometimes in young adulthood. The primary symptom of stenosis at any site is pain and fatigue resulting from pressure on the spinal cord or nerves.

People with stenosis of the central canal report pain that is sometimes vague and may come and go, but usually is noticeable in the lower back, lower extremities, or the buttocks. Pain and fatigue are generally worsened by walking or by extending the spine and relieved while sitting, leaning forward, or resting. While the actual site of narrowing is in the spine itself, it is the pressure on the nerves that generates the referred pain in the buttocks or legs. Symptoms of narrowing of the lateral recesses or intervertebral foramina (the "windows" where individual nerves exit the spine) more closely mimics sciatica or disc herniations – pain or changes in sensation that follow a single nerve pathway.

Cauda equina syndrome

Stenosis is a degenerative and chronic disease: It will continue to progress with age and with further trauma to the spine. In rare, advanced cases, people may also develop cauda equina syndrome. Cauda equina is Latin for "horse tail," and the condition is so named because the nerve roots, which extend out at the base of the spinal cord in a group of strands, resembling a horse's tail. This condition is characterized primarily by pain, but more importantly the following symptoms:

- urinary and/or bowel incontinence

- saddle anesthesia (numbness or tingling in the genital region extending to the anus and inner thighs)

- motor weakness.

How is lumbar spinal stenosis diagnosed?

To diagnose spinal stenosis, an orthopedic surgeon takes a detailed patient medical history, conducts a physical examination, and evaluates spinal imaging, including X-rays and advanced images obtained through either magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or computed tomography (CT scan).

X-rays of the spine show bony anatomy and alignment of the spine, while MRI shows the anatomy of the spinal canal. An MRI can be obtained without radiation or an invasive procedure. However, because it utilizes strong magnetic fields, some people cannot safely have an MRI (for example, patients with pacemakers or certain other implants). For patients who cannot undergo an MRI, a CT myelogram is a good alternative, but this requires an injection of contrast material (dye) into the spinal canal to improve visualization.

To confirm the diagnosis, the orthopedic surgeon will rule out the presence of vascular claudication, a condition that involves poor arterial circulation but which shares some of the symptoms of lumbar spinal stenosis.

The orthopedic surgeon will also do a thorough evaluation to determine whether other orthopedic conditions are present, such as osteoarthritis, which may be causing stenosis-like symptoms, and/or which may also require treatment along with the stenosis.

What are the treatments for lumbar spinal stenosis?

Treatment starts with nonsurgical options that may include physical therapy, NSAIDs or electrical spinal cord stimulation. If conservative measures don't work, pain relief may require a form of spinal spinal decompression surgery.

Nonsurgical treatments

Nonsurgical treatments typically include:

- physical therapy to strengthen muscular stabilizers of the spine and correct the forward-leaning posture many people with stenosis adopt to alleviate pressure on their spinal nerves

- NSAIDs (nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, such as ibuprofen) to treat inflammation of spinal joints and provide pain relief

- the application of ice, heat, ultrasound waves or electrical stimulation to the affected area

While the space within the spine cannot be expanded by these means, reducing inflammation can relieve some pressure on the nerves and offer pain relief. Unlike in conditions such as scoliosis, braces are not typically used to treat stenosis unless instability is present.

Spinal injections

If these measures do not provide adequate relief, another nonsurgical treatment option is a course of spinal injections. There are a variety of injections available, including different anatomical points and medications. Injections are generally performed by a physiatrist (a nonsurgical doctor of spine and musculoskeletal conditions), a pain management specialist, or an interventional radiologist – all of whom are available at HSS. Most commonly patients may be given a steroid (a potent anti-inflammatory agent) injection directly into the inflamed area to attempt to calm the region and relieve pressure. Images obtained by MRI or CT myelogram guide the placement of these injections.

Response to this treatment is variable. Sometimes pain relief is significant and long-lasting. Other individuals have brief or minimal pain relief and may or may not respond to a repeat injection. To minimize the side effects that can accompany treatment with steroids, the number of spinal injections is generally limited to three per year.

Individuals who experience temporary pain relief from these measures may still be candidates for surgical intervention. A positive response to injection treatment confirms that stenosis contributing to the patient's problem. Surgery, however, is only considered after other treatment options have been exhausted.

What is the surgery for lumbar spinal stenosis?

Similar to nonsurgical treatment, the goal of surgical intervention is to relieve pressure on spinal cord or the nerve roots. Relieving pressure on the nerves will alleviate pain and fatigue associated with stenosis and help restore patients’ mobility and quality of life. This is commonly achieved by performing a lumbar laminectomy. This is a type of spinal decompression surgery in which the lamina – the bony "roof" of the “house” analogy – is removed.

The orthopedic surgeon may also remove any bone spurs and soft tissues (for example, bulging discs or inflamed ligaments) that are compressing the spinal cord or its nerve roots. In doing so, the space through which the spinal cord passes is decompressed (opened) and the pressure on the nerves is eliminated. Newer surgical techniques (minimally invasive spinal surgery) allow for laminectomies and more-targeted decompressions to be performed using smaller incisions and less dissection. The choice of which particular surgical techniques to employ is decided on a case-by-case basis and individualized to the patient.

The physical extent of spinal stenosis is variable. It may affect anywhere from only one or two levels of the spine to more extensive disease throughout the lumbosacral spine (from the lumbar vertebrae down to the sacrum). Depending on the extent of the disease and presence of spinal instability, among other factors, some people may also require a fusion procedure in addition to their laminectomy.

Illustration of lumbar spine, sacrum and coccyx (tailbone).

Patients who undergo decompressive surgery can sometimes leave the hospital the same day of their surgery, or they may spend one to two nights in the hospital, depending on the extent of the planned surgery or discussions they have had with their surgeon. Physical therapy is initiated as soon as possible with an early focus on mobility, followed by a program of strengthening and stabilizing the muscles around the spine. The patient must avoid any back bending, twisting, and lifting for one to three months following surgery, depending on their surgical plan.

Overall, the success rate for surgical treatment of stenosis at HSS is about 85%, with varying degrees of improvement achieved among cases. Even if we can't get the patient back to all the physical activities he or she once enjoyed, we can often get them back to performing activities of daily living, without discomfort.

In addition to offering pain relief, treatment of stenosis confers a psychological benefit, as both mobility and good quality of life are returned to the patient.

Treatment for stenosis of the lumbar spine at HSS

Hospital for Special Surgery (HSS) has been committed to the development of research and clinical expertise in this area of medicine for several decades. Today, HSS Spine performs more than 4,000 spine surgeries per year – more than any other hospital in the United States – offers patients the benefit of a highly specialized team of orthopedic spine surgeons, physiatrists, nurses, anesthesiologists and physical therapists who all focus primarily on the treatment of spinal disorders.

(Find an HSS specialist who treats spinal stenosis.)