Degenerative Scoliosis: Causes, Symptoms, Diagnosis, Treatment

Summary: Degenerative changes of the spine are common in older people and may be associated with either osteoarthritis or osteoporosis. In some people, however, these changes can also result in a sideways curvature of the spine known as degenerative scoliosis. This article explains how and why the condition occurs, its common symptoms, and how orthopedic specialists diagnose it through advanced imaging techniques.

It also covers nonsurgical and surgical treatment options, including minimally invasive and robotic-assisted spine surgery.

What is degenerative scoliosis?

Degenerative scoliosis is a sideways curve in the spine that measures 10 degrees or greater and that develops in a grown adult as a result of spinal degeneration (osteoarthritis of the spine, also known as spondylosis).

What causes degenerative scoliosis?

The precise causes of degenerative scoliosis or associated spinal osteoarthritis are not known, but the condition is clearly aggravated by daily wear and tear, microtraumas and repetitive activities that jar the spine, such as using a jackhammer. Less frequently, it is caused by a fall or other trauma.

To understand how this process occurs, it is helpful to think of the spine as a series of bony blocks, the vertebrae, which are connected by facet joints that permit movement in the spine. discs sit between the vertebrae and provide cushioning and protection. The spinal cord runs through the spinal canal, a passage created by the vertebrae.

Degenerative (arthritic) changes in the spine can occur in either the facet joints or the discs. When For back pain due to symptoms coming from the arthritis develops in the facet joints, it is very similar to the process that occurs in the other joints of the body, where the joint cartilage wears down, causing bone-on-bone rubbing together of the ends of the vertebrae. When arthritis affects the discs (degenerative disc disease), the inner part of the disc – a jelly-like substance called the nucleus pulposis – can dry out as it ages. Alternately, the outer part of the disc – the thickly ligamentous annulus fibrosis – can develop rips and cracks as it wears. The cumulative degenerative changes in all three of these processes can result in spinal stenosis, in which the passage that surrounds the spinal cord and a group of nerves called the cauda equina become constricted and the nerves circumferentially compressed. (See also cauda equina syndrome.)

What are the symptoms of degenerative scoliosis?

Patients with degenerative scoliosis usually seek medical attention when they experience pain or other symptoms in the back, hip, buttocks, or legs. Pain in the back is typically related to spine arthrosis or muscle spasms, and can radiate into the buttocks, the thighs, and the hips. These are referred to as axial symptoms. Radicular symptoms result from compression or pinching of a nerve, and may include shooting pains, sometimes described by patients as "lightning bolts," sciatica, or numbness in the legs. These pains may take different pathways down the leg and foot, depending on the specific nerves compressed in the affected area of the spine.

Another manifestation of a compressed nerve is muscle weakness in the leg or foot; an example may be a condition called foot drop, in which the patient has difficulty lifting the front part of the foot. Patients with degenerative scoliosis who have developed stenosis may also experience fatigue when walking or a heaviness in the legs that subsides when the he or she leans forward or sits down.

How is degenerative scoliosis diagnosed?

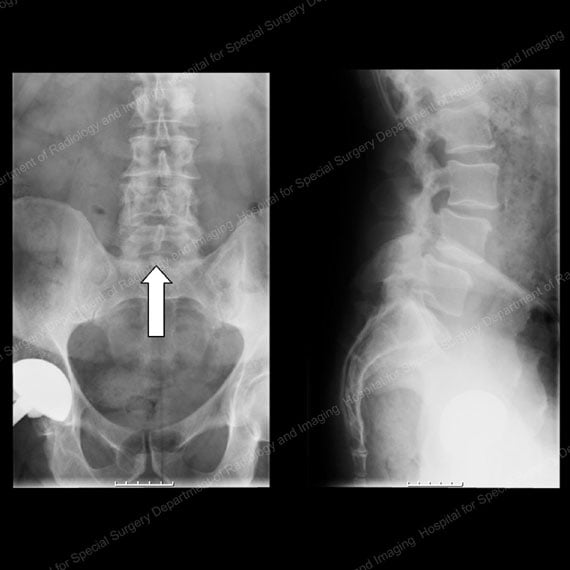

An orthopedic surgeon will get the patient's history, conduct a physical exam and order full spine X-ray images, low-dose radiation EOS images or, in some cases, a CT scan to confirm a diagnosis for degenerative scoliosis.

These images will be taken of the full spine from both the front and from the side. EOS imaging allows these to be taken simultaneously, without requiring the patient to reposition. CT scans can provide additional detail, including evidence of arthrosis (osteoarthritis) of the facet joints or the presence of small spinal fractures that may not be visible on X-ray images.

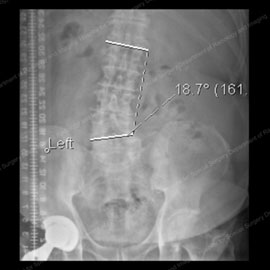

Figures 1 & 2: X-rays showing degenerative scoliosis in its first stages (left) and in a more progressive case (right).

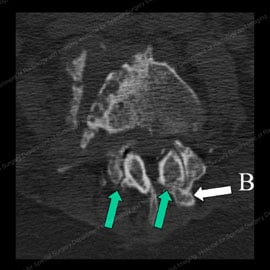

Figure 3 (left): CT scan showing normal facet joints with a green arrow pointing to the smooth and regular joint surfaces. Figure 4 (right): CT scan showing abnormal, osteoarthritic facet joints with thinned and irregular joint surfaces (shown by the green arrows) and bone spurs (noted with the letter B).

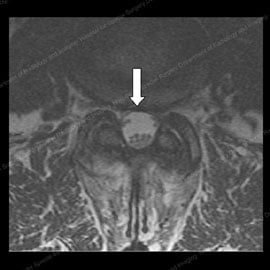

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may also be used to obtain information about the nerves, discs, and soft tissue in the spine. This is particularly helpful in determining the cause of radicular symptoms in the legs.

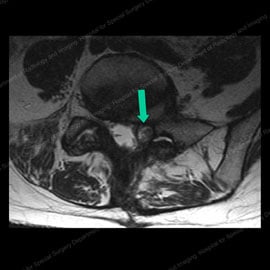

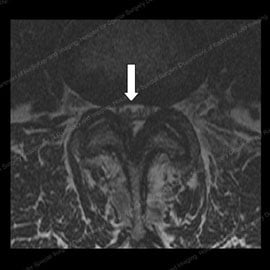

Figure 5 (left): MRI of a patient with a facet cyst (shown by the green arrow) causing compression of nerves. Figure 6 (right): MRI of same patient after facet injection and cyst rupture (shown by the green arrow), completely relieving the compression and eliminating the patient's pain.

When assessing a patient in whom degenerative scoliosis is suspected, the orthopedic spine surgeon looks at the angles in the spine as well as the balance of alignment between the head, spine, and hips. If a curve is present, it’s important to assess whether it is likely to progress and to find other factors that may be contributing to the patient’s deformity, such as spondylolisthesis, a condition in which one vertebra slides forward, backward, or sideways relative to the vertebra below. Spondylolisthesis suggests instability of the spine and can produce stenosis (abnormal narrowing of the spinal canal), pain, and sometimes nerve injury.

Figure 7 (left): X-ray showing a lateral view (from the side) of a normal spine. Figure 8 (right): X-ray showing anterior spondylolisthesis, also known as anterolisthesis. Note the white outlined arrow pointing to the affected vertebra.

What is the treatment for degenerative scoliosis?

Treatment may either be surgical or nonsurgical, on a case-by-case basis. Many patients can avoid surgery and achieve pain relief from non-operative means.

Is there nonsurgical treatment for degenerative scoliosis?

Nonsurgical treatments for degenerative scoliosis include:

- avoidance of activities that worsen symptoms

- physical therapy, Pilates or yoga to strengthen muscles

- moist heat or cold

- acupuncture

- spine manipulations

- oral medication

- injected medications

Oral medications

Patients who do not respond to activity avoidance or physical therapy measures may find relief with oral medications. For back pain, the orthopedic surgeon may recommend either a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) such as ibuprofen or naproxen, or a drug from the COX-2 inhibitor class of medications, such as celecoxib.

For radicular symptoms, drugs that reduce inflammation in the nerves and surrounding soft tissues may be prescribed, or drugs that reduce overactive nerves (neuroleptics) can be used to limit symptoms. Although the neuroleptic agents (such as gabapentin or pregabalin) can be very effective, they also depress the function of normal nerves and can leave patients with a rubbery sensation in the legs; in addition, some patients taking these drugs report feeling sleepy much of the time, a side effect that may fade over time. Antidepressants may also improve radicular symptoms, although the mechanism involved is not well understood.

Oxycodone is a common and typical narcotic to use on rare occasions to manage extreme pain symptoms. They can offer effective pain relief on a short-term basis; for example, in the week or so leading up to surgery or for a few weeks following surgery. However, these drugs are not a good choice long-term as the patient accommodates to the dose and requires increasingly greater doses of the drug to achieve pain relief. Moreover, they eventually become ineffective.

Injections

If oral drugs do not offer sufficient relief for axial and/or radicular symptoms in the back and legs, the patient may be referred to a physician specially trained in physiatry or pain management for injection-based treatment.

For back pain due to symptoms coming from the facet joints, the specialist may decide to perform a facet joint injection. Facet injections deliver two medications directly into the joint: a numbing agent and a corticosteroid which is intended to reduce inflammation.

Injections can be helpful in two ways. If the patient feels numb or "funny" in the injected area but pain is still present, we know we have not found the problematic facet joint. However, if the pain does go away, we know we’ve found the correct facet joint responsible for causing the pain symptoms. At this point, the cortisone reduces inflammation and diminishes – or in some cases completely relieves – pain for a matter of weeks to months. Because more than one facet joint may be affected in degenerative scoliosis, the patient may require multiple injections.

If pain returns after the facet injections, the specialist may consider a facet rhizotomy (also known as radiofrequency ablation), in which a special thermal probe is inserted near a small nerve just outside of the painful facet joint. The probe can then be heated up where it contacts the nerve and serves to destroy the nerve. This process of rhizotomy effectively switches off pain signals to the brain. This procedure can provide several months to years of relief.

In patients who are experiencing leg symptoms only, an epidural steroid injections can be considered. The concept of an epidural injection is that the needle is guided either from the midline skin or from the side, and the tip of the needle is advanced to an area near one of the spinal nerves that is either inflamed or is being irritated by inflammatory tissue. A slightly different epidural technique is called a caudal, where the needle is inserted at the base of the spine. With any of the techniques used, the purpose is to deliver corticosteroids to bathe the affected nerve roots, thereby reducing inflammation and pain (see Figure 6, above).

Injection therapy may continue to be effective for some time; however, patients in whom it is ineffective, or in whom it becomes ineffective, may eventually be candidates for surgery.

What is the surgery for degenerative scoliosis?

A patient may require a spinal fusion, spinal decompression surgery, or both. If the patient’s pain is restricted to the back and degenerative changes in the facet joints, fusion in the affected area may be recommended.

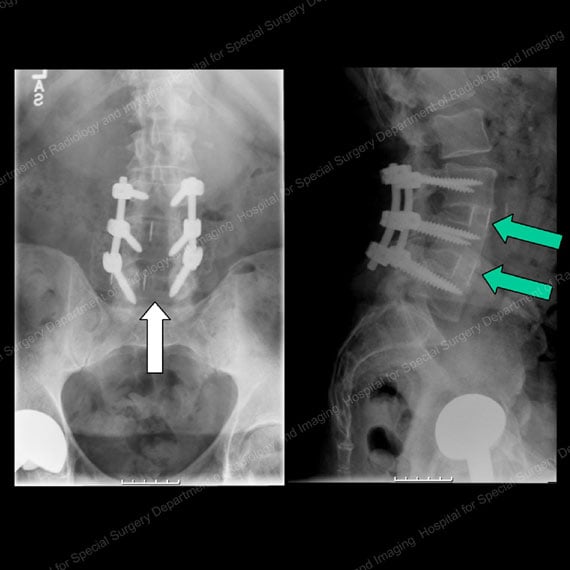

In fusion surgery, the vertebrae are essentially "welded" together, with screws or other instrumentation being used to secure and immobilize the bone. The goal is to eliminate the pain associated with movement in that area.

Figure 9 (left): X-ray of a patient with degenerative scoliosis (50+ degrees) and lateral spondylolisthesis prior to fusion surgery. Figure 10 (right): X-ray of the same patient after fusion surgery with instrumentation, which eliminated her listhesis and reduced her curve to 10 degrees.

In the presence of spinal stenosis and radicular symptoms, decompression surgery (also known as laminectomy) is performed to take pressure off the nerves, a procedure that involves the removal of bony structures, ligaments, and in some cases, other soft tissues that help to support the spine.

Figure 11 (left): MRI of a patient prior to spine decompression surgery, with a triangular nerve space (shown by the white arrow). Figure 12 (right): MRI of the same patient after spine decompression surgery, with an increased nerve space and 90% improvement in stenosis and radicular symptoms.

In determining the appropriate surgery, we have to look at the entire spine,. For example, although the patient with degenerative scoliosis may only have radicular symptoms, if we perform a decompression only and do not stabilize the scoliosis, the resulting instability generated by the removal of bone and ligaments can be problematic. Therefore, fusion may be necessary, in addition to the decompression, to maintain the stability of the spine. If we find spondylolisthesis at one or more levels of the spine, we can expect this deformity to progress, and we typically need to address this with a combined decompression and fusion as well.

Figures 13 & 14: X-rays showing patient from the front (left) and side (right) prior to decompression and fusion surgery for stenosis and anterolisthesis. Note the bone in the center of the spinal canal in the image on the left, as shown by the white arrow.

Figures 15 & 16: X-rays showing the same patient from the front (left) and side (right) one year after decompression and fusion surgery. Note the absence of bone in the center of the canal in the image on the left, as shown by the white arrow, due to the decompression. Also note the excellent fusion bone produced in the cages between the vertebral bodies in the image on the right, as shown by the green arrows. The instrumentation (rods and screws) can be seen in the center of each image.

Our goal in surgery is to alleviate the pain, restore and maintain stability, and to correct the curve as much as is safely possible. To help protect the patient during surgery, the nerves are monitored through wires attached to the skin in the arms and legs, which are then connected to a computer for interpretation, and are overseen by an HSS neurologist.

What are the results for degenerative scoliosis treatments?

For the majority of patients with degenerative scoliosis, pain relief or reduction can be achieved with aggressive use of nonsurgical measures. In patients for whom surgery becomes necessary, the results vary with the underlying problem. Patients who undergo decompression for stenosis or radicular symptoms almost always have an improvement in symptoms. Those whose pain, numbness, or weakness was intermittent prior to surgery tend to experience the greatest benefit.

Patients with degenerative scoliosis who undergo fusion of the spine for isolated back pain have results that are comparable to those achieved in patients with degeneration and straight spines.

Good outcomes are also based on appropriate assessment of surgical candidates by a multidisciplinary team, especially in an older population. Whenever we consider surgery, we have to ask these questions:

- Does the patient have other medical problems that will make it difficult to tolerate surgery or to participate in rehabilitation?

- Is she or he taking any medication that will interfere with surgery and recovery, and is it necessary to stop these medications temporarily?

Future directions in treatment

In order to continue improving outcomes in treatment, we are looking at ways to optimize bone tissue. Substances called bone morphogenic proteins (BMPs) may actually help build bone and already have a role in augmenting spinal fusions. In addition, ensuring that patients are not Vitamin D and/or calcium deficient can help to strengthen the bone and improve the patient’s ability to tolerate the insertion of rods, screws, and other instrumentation, as needed. Use of systemic bone building agents (teriparatide and abaloparatide, among others) are also being evaluated as possible fusion augmenting agents in the “tool box” of interventions to be considered to optimize the success of spine fusion surgeries.

Minimally invasive spine surgery techniques have become the mainstream in the past 10 years, particularly as this relates to implant cages and lumbar interbody fusions (LIFs) done in the spinal disc space. These procedures include the anterior LIF (ALIF surgery), lateral LIF (LLIF surgery), transforaminal LIF (TLIF surgery) and posterior LIF (PLIF surgery). More recently, use of computer-assisted navigation has allowed placement of the posterior rods and screws percutaneously, and in the past couple of years we have progressed to robot-assisted surgeries which have further refined the accuracy, precision and safety of minimally invasive surgery for most of the procedures needed to treat these patients. These advances minimize soft tissue trauma, make surgery better tolerated by patients, and allow them to become mobile again more quickly following surgery.

This makes good sense for patients who require short fusions, or longer fusions that are straightforward. However, for those who require more extensive surgeries involving spinal decompressions and fusions, traditional "open" approaches may be unavoidable.

Key takeaways

- Definition: Degenerative scoliosis is a spinal curve of 10° or more that develops in adults due to arthritic and degenerative changes.

- Causes: Aging, repetitive strain, minor trauma, or spinal instability from spondylolisthesis can lead to uneven degeneration and curvature.

- Symptoms: Back, hip, or leg pain; sciatica; numbness or weakness (such as foot drop); and fatigue or heaviness in the legs when walking.

- Diagnosis: Full-spine X-rays, EOS imaging, CT, or MRI to assess curvature, nerve compression, and spinal alignment.

- Nonsurgical treatment: Activity modification, physical therapy, heat/cold therapy, oral medications (NSAIDs, COX-2 inhibitors, gabapentin), and targeted injections (facet, epidural).

- Surgical treatment: Fusion and/or decompression to relieve nerve compression, stabilize the spine, and correct the curve.

- Outcomes: Most patients improve with nonsurgical care; surgery provides significant pain and function relief when needed.

- Future directions: Bone-strengthening therapies (vitamin D, BMPs, anabolic agents) and advanced, minimally invasive or robot-assisted fusion techniques are enhancing precision and recovery.

Scoliosis Success Stories

References

- York PJ, Kim HJ. Degenerative Scoliosis. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med. 2017 Dec;10(4):547-558. doi: 10.1007/s12178-017-9445-0. PMID: 28980155; PMCID: PMC5685967. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28980155/