Kyphosis

Summary: This article explains kyphosis, the forward curvature of the spine, and explains normal spinal alignment versus an excessive curvature, known as hyperkyphosis. It outlines common causes, how kyphosis is diagnosed and possible treatment options, ranging from posture correction and physical therapy to complex spine surgery, including recovery after surgery.

What is kyphosis?

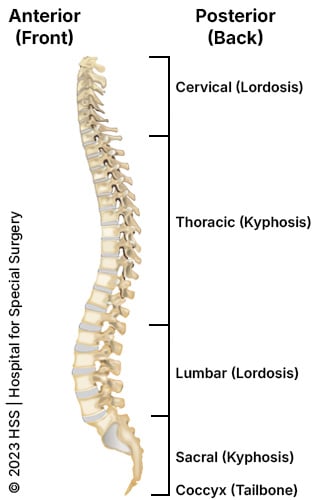

Kyphosis is a term used to describe the direction of the spine’s curvature as seen from the side-view of the body. Namely, kyphosis refers to a forward (“anterior”) curvature of the spine. This is opposite from lordosis, which refers to a backward (“posterior”) curvature of the spine.

A normally aligned spine will have lordosis in the lumbar region (lower back) and cervical (neck) region, and kyphosis in the thoracic (chest) region.

Illustration of human spine from the left side, showing the kyphosis and lordosis curvatures.

The amount of curvature in each part of the spine must be proportional for a person to stay upright. For example, viewed from the side, some people have spines that look like an “S,” while others have spines that are straighter. In other words, people with a lot of lordosis in the lumbar spine usually have more kyphosis in the thoracic spine in order to keep their entire body balanced.

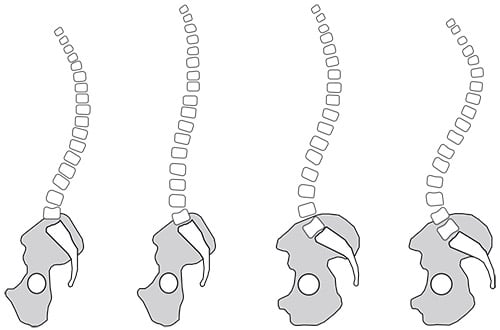

The spine viewed from the side with the person facing to the left. There is a spectrum of normal spine shapes. Notice that some spines have greater curves than others.

What is hyperkyphosis?

While a degree of kyphosis curvature in the spine is normal, disproportionate kyphosis is pathologic (anatomically abnormal). When kyphosis in one region is out of proportion to the other sections of the spine, this can cause pain or deformity. Excessive or pathologic kyphosis is called “hyperkyphosis.” While hyperkyphosis most commonly occurs as a pathologic condition in the thoracic spine (mid-back), it can occur in the cervical or lumbar spine (lower back) as well. Hyperkyphosis is sometimes also referred to as “roundback,” and is also commonly shortened to simply "kyphosis," even though the latter term technically refers to the type of curve, rather than a pathology of the curve.

This article will discuss problems of thoracic hyperkyphosis (pathologic kyphosis of the thoracic region of the spine), but the shortened term “kyphosis” will be used in place of “hyperkyphosis” throughout.

What is the most common cause of thoracic kyphosis?

The most common causes of thoracic kyphosis are years of poor posture in childhood (postural kyphosis) and structural changes of the vertebrae (Scheuermann’s kyphosis). Both issues usually become noticeable by adolescence.

Kyphosis can also develop after spine trauma or spine surgery. Less common causes of kyphosis include skeletal dysplasias (such as achondroplasia), abnormalities in vertebral development (congenital kyphosis), and neuromuscular disorders.

Postural kyphosis

Postural kyphosis is caused by poor posture in childhood which, over time, affects the muscles and soft tissues of the back, allowing the thoracic spine to curve forward excessively. Unlike kyphosis caused by abnormalities in the vertebrae, this type of kyphosis is caused by muscle weakness and is not treated surgically.

Scheuermann’s disease

Scheuermann’s disease, also known as Scheuermann’s kyphosis, was originally described in Northern European male teenagers. In contrast to patients with postural kyphosis, patients with Scheuermann’s disease have abnormalities in the thoracic vertebrae and the discs. Specifically, some of their thoracic vertebrae are trapezoidal in shape, a defining feature of the disease. This leads to a kyphosis that is structural and can be treated surgically if it is severe.

Radiographs of a patient with Scheuermann’s kyphosis who underwent corrective surgery (spinal fusion with instrumentation).

While Scheuermann’s disease most commonly occurs in the thoracic spine, it can also occur in the vertebrae between the thoracic and lumbar spine. This is called “thoracolumbar Scheuermann’s disease.”

Other types of kyphosis

In the thoracic region, kyphosis is often a result of compression fractures in the spine, which occurs with osteoporosis (low bone density). Traumatic fractures, such as after a car accident, can also lead to post-traumatic kyphosis. Kyphosis can also be a result of neuromuscular disorders such as cerebral palsy, muscular dystrophy, Parkinson’s disease, or polio. In very rare cases, excessive kyphosis can be caused by spinal bone tumors or soft-tissue tumors.

Kyphosis can also occur after spine surgery. After lumbar fusions for correction of adult scoliosis, kyphosis can occur above the fusion due to the stress between the fused and the non-fused parts of the spine. This is a difficult problem that surgeons have yet to solve in a comprehensive manner. In the cervical region of the spine (neck), kyphosis can occur after cervical laminectomy (removal of the posterior bony arch in the cervical spine to decompress the spinal cord). This is called “post-laminectomy kyphosis” and was very common before surgeons learned to prevent this complication by performing fusions with the cervical laminectomy. Therefore, post-laminectomy cervical kyphosis is less common today.

Kyphosis and osteoporosis

Osteoporosis refers to a reduction in bone density. Aging is the most common cause of osteoporosis, especially in women. Post-menopausal women who have a reduction in bone density due to osteoporosis may develop what was historically called the “dowager’s hump.” Before we understood how to screen for low bone density, many women developed osteoporosis, which put them at risk for vertebral compression fractures. In the thoracic spine, “wedge-type compression fractures” can occur. This means the vertebra fractures and collapses anteriorly (in the front), while remaining intact posteriorly (in the back). This process led to many women having a “dowager’s hump.”

Osteoporosis-related kyphosis is usually not treated surgically given that the bone cannot support the implants necessary to correct the excessive kyphosis. Therefore, the only way to fix a dowager’s hump is by preventing it in the first place.

At HSS we recommend that all women undergo age-appropriate screening for bone density. This is especially important for perimenopausal women. We recommend that women ask their primary care doctors to be screened for osteoporosis. For patients with advanced osteoporosis or bone diseases that lead to low bone density, they can meet with osteoporosis specialists at the HSS Osteoporosis and Metabolic Bone Health Center.

What does kyphosis look like?

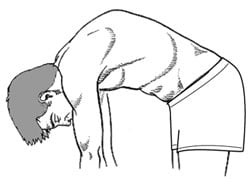

Postural kyphosis usually becomes noticeable during adolescence and occurs more commonly in girls than in boys. Parents may perceive an abnormal prominence in the young person’s posture, or it may be detected during a routine visit to the pediatrician.

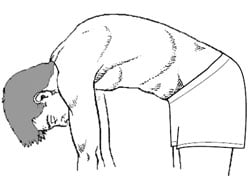

Illustration of a normal spine with forward bending.

Illustration of increased prominence from Kyphosis with forward bending.

How is kyphosis diagnosed?

A diagnosis is made on the basis of physical examination and with radiographs (X-rays). Both are needed to determine whether the kyphosis is postural or due to structural changes in the vertebrae.

Can kyphosis be corrected?

Most patients with postural kyphosis can achieve good results – correction of the curve to within the normal range – with education in proper posture and participation in a physical therapy exercise program.

When kyphosis occurs due to changes in the vertebrae (such as from Scheuermann’s disease, fractures, tumors, etc.), it can be corrected with surgery. The type of surgery to correct kyphosis is dependent on the cause of the kyphosis. Since kyphosis occurs over many vertebral levels, surgery to correct kyphosis is usually a large undertaking.

What is the best treatment for Scheuermann’s kyphosis?

The best treatment for Scheuermann’s kyphosis is one that balances the risk of surgery with the disability of the patient. For patients with manageable back pain, the risks of surgery are rarely worth the potential benefits. However, for patients with rapidly progressing deformity or who are disabled by their back pain, the benefits of surgery may be worth the risks. Surgery is rarely considered unless the kyphosis is greater than 70 degrees, and many patients with curves of 70 degrees or more never need surgery at all.

What happens if kyphosis is left untreated?

The progression of kyphosis is dependent on the cause of the kyphosis. If a patient has kyphosis from vertebral compression fractures resulting from osteoporosis, and they do not treat their osteoporosis, then the kyphosis will progress. On the other hand, if that same person decides to take medications for osteoporosis to increase their bone density, they may be able to greatly slow or even stop the progression.

For Scheuermann’s kyphosis, a disease for which we do not know the cause, the likelihood of progression is often based on the history of progression through growth. For example, if a healthy, fit 35-year-old has Scheuermann’s disease and 70 degrees of kyphosis, it is unlikely this will progress much into adulthood. However, a 12-year-old with Scheuermann’s disease and 70 degrees of kyphosis is likely to progress by a significant degree as they have a significant amount of growth remaining.

Ultimately, the rate of progression is individually determined. Patients with kyphosis should make sure they follow up with their surgeons or spine specialists to take periodic X-rays. This helps the patient and surgeon anticipate the need for treatment or for continued observation.

What is the surgery for kyphosis?

When surgery is indicated, as is often the case in Scheuermann’s kyphosis, an orthopedic surgeon will restore physiologic alignment to the spine by performing one or more of the following procedures: removing abnormal discs, fusing the affected vertebrae together, and placing instrumentation in the spine as needed to maintain correct posture while the vertebrae fuse together.

A posterior surgical approach (accessing spine from the back) is the most common method. However, patients with a large, rigid curve may also require an additional procedure with an anterior approach (through the chest).

What is the recovery time for kyphosis surgery?

With increasingly sophisticated surgical techniques and instrumentation, surgical treatment for kyphosis is easier to recover from than ever before. Patients who require only one posterior procedure (incision in the back) are up and out of bed the next day. Patients may not need to wear a brace following surgery. General anesthesia is used during these surgeries and hospitalization lasts between four to six days depending on the extent of surgery and age. Physical therapy after surgery is generally started once the bones have some time to heal (usually three to six months).

In patients with good bone quality, excellent results can be achieved. Success is defined as a solid fusion that reduces pain and in which the magnitude of the curve is decreased while maintaining a balanced spine.

Key takeaways

- Normal kyphosis is part of healthy spinal alignment, but hyperkyphosis is an abnormal forward curvature that can cause pain, deformity, and functional issues.

- Common causes include postural kyphosis from muscle weakness, Scheuermann’s disease (structural vertebral changes), osteoporosis-related fractures, spine trauma, and neuromuscular disorders.

- Diagnosis involves physical examination and X-rays to distinguish between postural and structural kyphosis.

- Postural kyphosis often improves with posture education and targeted physical therapy, while structural kyphosis may require surgery in severe or progressive cases.

Osteoporosis prevention and treatment are critical in reducing the risk of kyphosis caused by vertebral compression fractures. - Surgery for kyphosis is usually considered only for large, rigid curves or disabling pain, with fusion and instrumentation being the most common corrective approach.

- Recovery from surgery typically includes a short hospital stay, early mobilization, and gradual return to activity, with good outcomes in patients with healthy bone quality.

Medically reviewed by Bernard A. Rawlins, MD ; Francis C. Lovecchio, MD