Developmental Dysplasia of the Hip (DDH) in Infants and Young Children: Causes, Symptoms, Treatments

What is developmental dysplasia of the hip?

Developmental dysplasia of the hip (DDH), also known as developmental pediatric dysplasia of the hip or hip dysplasia, describes a spectrum of hip joint abnormalities that vary in severity from a complete dislocation of the hip joint to mild irregularities of the located hip joint.

Hip dysplasia may develop in a baby around the time of birth or during early childhood. Although it is commonly diagnosed in babies and young children, DDH also affects adolescents and adults. This can usually be attributed, however, to milder cases of DDH that are difficult to diagnose and may have been untreated as a child.

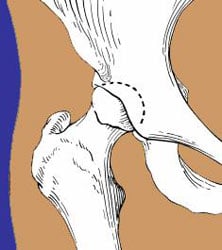

Illustration of the femur and acetabulum meeting in a healthy hip joint.

In the healthy hip joint, the upper end of the femur (thighbone) meets the acetabulum to fit together like a ball and socket, in which the ball rotates freely in the socket. Cartilage, a smooth protective tissue, lines the bones and reduces friction between the surfaces during movement.

In DDH, however, there is an abnormal relationship between the components of the hip, and often the hip socket is underdeveloped and does not support the femoral head (ball).

The conditions encompassed by the term hip dysplasia include:

- dislocated hip: where there is no contact between the cartilage on the ball and the cartilage on the socket

- dislocatable hip: where the ball easily pops in and out of the socket

- subluxatable hip: where the cartilage of the ball and the socket are touching, but the ball is not properly seated in the socket

- dysplastic hip: where the hip socket or acetabulum is underdeveloped or deficient to support the ball (more common in older adolescents and adults than in pediatric patients)

Anterior-to-posterior (front-to-back) preoperative X-ray of a dislocated right hip in toddler (shown at left).

In children, hip dysplasia more frequently affects the left hip than the right. About 80% of cases follow this pattern. The condition can, however, be present in both hips.

Can hip dysplasia correct itself?

Some mild forms of developmental hip dysplasia in children – particularly those in infants – can correct on their own with time.

Who is at risk for hip dysplasia?

Hip dysplasia is much more common in girls than in boys, and it tends to run in families. Even among children who have no hereditary link, there is a greater risk in all first-born children. Babies who are breech in utero are also at risk for DDH.

What causes hip dysplasia?

Genetics plays a strong role, but other influences during pregnancy and birth – such as congenital conditions caused by the fetus being in a uterus that is too small – and cases of breech birth can also lead to developmental hip dysplasia.

Family history

The risk of hip dislocation at birth is approximately one in 1,000. If a parent experienced hip dysplasia during childhood, the risk of his or her own child developing this risk increases by 12% compared to a parent with no history of the condition. A child whose sibling has hip dysplasia will have a 6% higher chance of developing the condition.

Molding abnormalities in the uterus

Head tilt (torticollis) and the turning in of the front of the foot (metatarsus adductus) are congenital conditions that often the result of being constrained in a uterus that is too small. These conditions alert medical professionals to be on the lookout for the presence of hip dysplasia, which can also be caused by such constraint.

Breech birth

This is when the baby emerges from the birth canal buttocks-first instead of headfirst. A breech-birth child is 10 times more likely to develop hip dysplasia than a child born headfirst.

What are the signs and symptoms of developmental hip dysplasia in children?

When present at birth, the abnormality may be detected during a routine physical examination of the newborn baby. Other signs include a leg length discrepancy, restricted range of motion in the hip, or a limp or waddle in walking in toddlers.

During a routine examination of a newborn, the physician gently flexes the child's hips in different directions. If the hip is dislocated or can be easily dislocated or subluxated (partially dislocated), the doctor may feel a "clunk" as the hip moves out of alignment. In a smaller percentage of cases, the problem does not become apparent until later in infancy or early childhood. Later diagnosis of hip dysplasia may be detected during routine examinations of hip stability in the pediatrician's office.

Additional signs that may bring undiagnosed developmental hip dysplasia to the attention of parent and physician include:

- a limb length discrepancy (one leg shorter than the other) on the affected side

- a limp

- a waddling gait (indicating both legs are affected)

- restricted range of motion of the hip joint (that initially may be detected by the caregiver when changing a diaper)

- unilateral tip-toe walking (walking on the tips of the toes on one foot, while the other foot remains flat on the ground)

To confirm a diagnosis of developmental hip dysplasia in children up to four to six months of age, an orthopedist uses ultrasound imaging. This technology offers a significant advantage over conventional a X-ray because images may be taken while the hip is in motion. "This is an accurate and safe diagnostic tool since there is no radiation," according to Ernest L. Sink, MD, Chief of the Hip Preservation Service at HSS. In children older than six months, X-rays, which show bone detail better, are used to confirm the diagnosis.

How is hip dysplasia treated?

Early intervention is essential to ensure the bones that make up the hip joint develop properly. Incorrect growth in either the ball or socket can cause formation problems in the other. The goal is to achieve and maintain joint congruity. "The acetabulum and the femoral head are dependent on one another for normal growth and development," explains Dr. Sink. "If the ball does not fit tightly into the socket, providing a specific growth stimulus, the socket may become too flat and unable to accommodate a sphere. In turn, without proper contact with the acetabulum, the femoral head and neck will not grow normally."

Does hip dysplasia always require surgery?

When treatment is required, the first choice for children under six months old is nonsurgical, using a Pavlik harness. In the minority of cases where this does not work, and in children not diagnosed until after six months of age, surgery may be required.

Pavlik harness

The Pavlik harness is a soft brace that gently redirects the head of the femur into the depth of the socket or acetabulum, which stimulates normal development of the joint.

Usually, the harness generally is used for three months. Initially, the child will wear the harness full-time and, as the hip position improves and stability is achieved, this can be reduced to part-time use. Treatment with the Pavlik harness is successful in about 85% of dislocated hips in children under six months of age.

Photo of an infant in a Pavlik harness.

Unfortunately, the Pavlik harness is not a good treatment option for older children because the hip has become more fixed in the dislocated position and is more difficult to realign.

Reduction

For the small number of patients in whom treatment with the Pavlik harness is not successful, and for children in whom the diagnosis is not made until after they are six months old, the orthopedist may recommend either a closed reduction or open reduction surgery. Reduction is a procedure in which the bones are realigned or put back into place to optimize hip joint congruity. Reduction procedures are performed by pediatric orthopedists with specialized experience in the treatment of hip dysplasia. There are two types of reduction:

- Closed reduction: Although no incisions are made in this procedure, it does require the child to be placed under general anesthesia. During a closed reduction procedure, the physician uses radiography to observe the hip and then gently manipulates it into proper alignment, without making any incisions. A cast is then applied to hold the hip in place for up to three months.

- Open reduction: In an open reduction, also performed under general anesthesia, a surgical incision is needed to remove any tissue that is keeping the femoral head from proper alignment in the socket. A cast is then applied as well.

Arthrogram image of dislocated hip in the operating room.

MRI image of relocated (anatomically aligned) hip.

Closed reduction and spica cast

Following closed reduction of the hip, the patient is placed into a spica body cast for 12 weeks to maintain proper alignment of the hip ball and socket. At HSS, we use cross-sectional, 3D MRI imaging of the hip after closed reduction in order to confirm appropriate location of the hip and confirm hip joint congruency. HSS prefers to use MRI imaging, rather than X-rays or CT scans, since radiation is not involved.

Photo of an infant in a spica cast.

Open reduction surgery for hip dysplasia

Treatment by open reduction is generally reserved for children greater than 10 months of age who have new diagnosis of a dysplastic hip, or in cases in which a prior, closed reduction of the hip was unsuccessful.

In this procedure, the surgeon makes an incision, removes any obstacles to anatomic realignment of the hip (such as adjusting tight muscles or other soft tissue) and relocates the femoral head into the acetabulum. The surgeon may also need to restore normal anatomy by performing a hip osteotomy, a procedure in which cuts are made to the femur and/or the acetabulum in order to adjust the angles at which the bones meet and optimize joint congruity. The need for a femoral or periacetabular osteotomy increases with the age at which diagnosis is made. It is usually required to correct abnormal development of the bones in any child over age three or four.

Preoperative view of a right hip dislocation, where the right leg appears shorter than the left.

Anterior-to-posterior (front-to-back) X-ray image, six months after open reduction with a realigned right hip.

All reduction procedures, including those that involve an osteotomy, are done on an inpatient basis and require the use of general anesthesia. Children who undergo open reduction wear a cast for a period of six to eight weeks. Once the cast is removed, he or she usually continues to wear a brace at night until the orthopedic surgeon determines that the hip joint is developing normally.

In some patients who have an open or closed reduction and/or a femoral osteotomy, an osteotomy of the pelvis may also be required to adjust the angle of the acetabulum. In younger patients, the procedure often used is the Pemberton or Dega osteotomy, in which the bony and cartilage roof of the hip is reoriented into normal alignment.

Anterior-to-posterior (front-to-back) X-ray showing residual

acetabular dysplasia on the right hip (shown at left).

Immediate postoperative X-ray after Dega pelvic osteotomy.

X-ray: Pelvis and hip 18 months after Dega pelvic osteotomy.

What are the risks of DDH treatments?

The risks associated with surgery – bleeding, infection and those associated with anesthesia – are minimal. Pediatric orthopedists take special care to avoid a condition called avascular necrosis (also known as AVN or osteonecrosis), in which the bones of the hip joint do not receive enough blood. This can be caused if the femoral head (the ball of the hip joint) is put back into the acetabulum (socket) with unnecessary pressure, and so minimal pressure is used. Avascular necrosis can result in abnormal growth of the bone.

"Regarding the safety of these procedures, what I usually tell parents is that the primary risk with a diagnosis of developmental hip dysplasia is not doing anything at all," says Shevaun Mackie Doyle, MD, from the Pediatric Orthopedic Service at HSS. "Untreated, these children face a high risk of developing osteoarthritis as adults, with the associated degenerative changes that cause chronic and progressive pain and stiffness."

Although the numbers are difficult to define, some members of the medical community believe that up to 50% of adults who eventually require hip replacement due to osteoarthritis, have developed the disease as a result of a pediatric hip problem. The majority of those cases are thought to be hip dysplasia.

What kind of outcome can a child with DDH expect?

The earlier the condition is treated, the better the chance of a successful outcome, meaning a hip that appears anatomically normal both during physical examination and on X-ray. Children who are treated for hip dysplasia are examined at regular intervals until they are skeletally mature (when growth is completed), to ensure that normal development continues. In some cases, a dislocated hip that was successfully reduced may still develop dysplasia in later years, requiring additional treatment.

References

- Ellsworth BK, Bram JT, Sink EL. Hip Morphology in Periacetabular Osteotomy (PAO) Patients Treated for Developmental Dysplasia of the Hip (DDH) as Infants Compared With Those Without Infant Treatment. J Pediatr Orthop. 2022 Jul 1;42(6):e565-e569. doi: 10.1097/BPO.0000000000002137. Epub 2022 Mar 10. PMID: 35667051.

- Heneghan M. Developmental dysplasia of the hip. JAAPA. 2021 Aug 1;34(8):48-49. doi: 10.1097/01.JAA.0000758256.52498.da. PMID: 34320541.

- Swarup I, Ge Y, Scher D, Sink E, Widmann R, Dodwell E. Open and Closed Reduction for Developmental Dysplasia of the Hip in New York State: Incidence of Hip Reduction and Rates of Subsequent Surgery. JB JS Open Access. 2020 Feb 3;5(1):e0028. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.OA.19.00028. PMID: 32309756; PMCID: PMC7147636.

- Martino R, Carry P, Adams J, Brandt A, Sink E, Selberg C. The Optimal Age for Surgical Management of DDH Differs by Treatment Method. J Pediatr Orthop. 2024 Jan 1;44(1):7-14. doi: 10.1097/BPO.0000000000002569. Epub 2023 Nov 16. PMID: 37970702.

- Ondeck NT, Borsinger TM, Chalmers BP, Blevins JL. Correcting Hip Dysplasia in Young Adults: Intraoperative Navigation and Outcomes. HSS J. 2023 Nov;19(4):501-506. doi: 10.1177/15563316231193003. Epub 2023 Sep 22. PMID: 37937090; PMCID: PMC10626937.