Common Conditions of the Foot and Ankle: An Overview

Common injuries and ailments affecting the foot and ankle range in complexity from simple ankle sprains to arthritis to traumas that affect multiple structures. Because the foot and ankle are made up of an intricate, interconnected network of bones, tendons and ligaments that are also weight-bearing, damage to these parts of the body can be quite disabling. “An injury or condition that affects one part of the foot or ankle can impact adjacent structures and have a cascading effect that can lead to additional problems,” explains Matthew M. Roberts, MD, Chief Emeritus of the Foot and Ankle Service. For this reason, it is advisable to seek prompt medical attention for foot pain, or any issue affecting the foot or ankle.

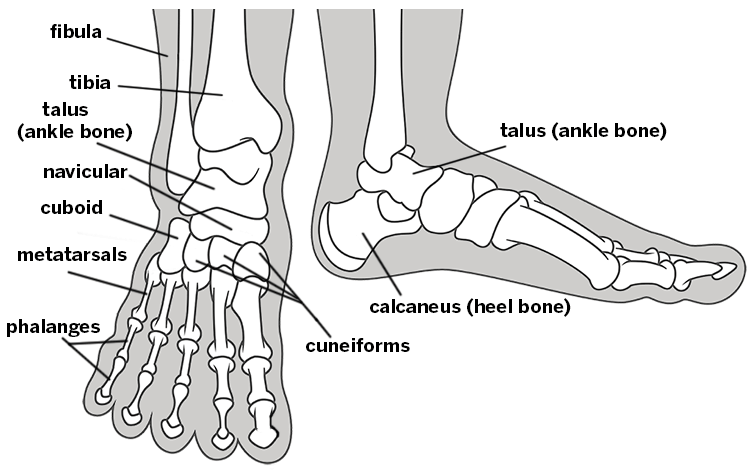

Figure 1. Skeletal structures of the foot and ankle

Many injuries and conditions of the foot and ankle can be treated without surgery, but when an operative procedure is needed, recent advances allow orthopedic surgeons to offer a broader range of options than were formerly available. While in the past, postsurgical pain had sometimes been a concern, patients can now benefit from innovative anesthesia methods that combine different modes of pain control techniques to minimize discomfort. An example is the popliteal nerve block, an injection used in conjunction with other regional anesthesia methods to numb the lower leg for at least 24 hours after foot and ankle surgery. These anesthesia techniques minimize the need for postoperative narcotic medications. In addition, with their pain well controlled, most patients do not require an overnight stay in the hospital.

Owing to the demands of weight bearing, and depending on the procedure, recovery from foot and ankle surgery may take several months. Most patients achieve 85% of healing at three months, with gradually diminished swelling and return of full strength in the affected area thereafter. By following prescribed guidelines for rest and physical therapy, most patients achieve excellent results.

- Arthritis in the Big Toe Joint

- Metatarsalgia

- Morton’s Neuroma

- Plantar Fasciitis and Heel Pain

- Flatfoot Deformity and High Arches

- Ankle Sprains

- Ankle Arthritis

- Achilles Tendon Ruptures

- Seeking Treatment for Foot and Ankle Problems

Bunions are more than a cosmetic issue

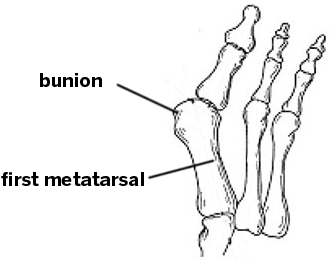

Bunions, which are seen more frequently in women than in men, are among the most common conditions affecting the forefoot. Also called hallux valgus, a bunion develops when the first metatarsal (the midfoot bone at the base of the big toe) drifts away from the metatarsals of the other toes. This widens the forefoot and causes the big toe to be pulled toward the second toe. The bunion is the prominent head of the first metatarsal [Figure 2]. With overlying soft-tissue thickening and bone spur formation, the protruding bunion may gradually enlarge and become more tender with shoe wear.

Figure 2. Forefoot anatomy, showing deviation of the first

metatarsal, widening of the forefoot, and prominent bunion.

Dr. Roberts explains the fundamental problem is that, with the angulation of the first metatarsal, the bone does not bear its “fair share” of the body’s weight. This can cause not only bunion formation but also crossover toes, hammertoes and metatarsalgia – chronic pain and tenderness in the ball of the foot. Although wearing tight or pointed shoes can exacerbate bunions, ill-fitting footwear does not cause the condition, which is believed to be hereditary. The disorder has been found in populations of nonindustrial societies where shoes are not worn.

If a bunion is primarily an inconvenience or cosmetic concern, finding shoes that accommodate the bunion to relieve discomfort may be advised. However, in patients whose bunions are progressing and impacting other areas of the foot, a surgical procedure that realigns the first metatarsal may be needed. After performing an osteotomy (cutting across the bone) to restore normal alignment and foot mechanics, screws are used to secure the bone during healing. The prominent bunion is also removed. Simply removing the “bump” without realigning the first metatarsal will not provide lasting relief; proper weight bearing in the foot will not be restored, and the bunion will recur. For more information about the treatment of bunions, read Minimally Invasive Bunion Surgery.

Arthritis in the big toe joint

In addition to being the site at which bunions may become apparent, the joint at the base of the big toe can also develop arthritis. When arthritis is present, owing to a loss of cushioning cartilage in the metatarsal phalangeal joint – where the metatarsal meets the phalanx bone in the toe – stiffness and pain develop. In some cases, the patient also develops a bone spur, or bump on the top of the joint, which can cause additional discomfort. Arthritis in the toe may have a genetic origin, or it may result from an injury.

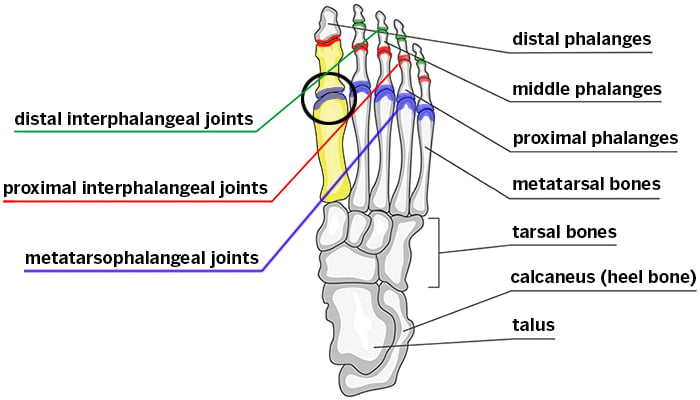

People who develop this condition, called hallux rigidus, [Figure 3] are counseled to wear shoes that have more rigid soles or with rocker bottoms, which are designed to transfer weight, reduce pressure and limit big toe motion. Some running shoes can also provide sufficient support. Going barefoot or wearing a flexible-soled shoe will exacerbate the condition.

Figure 3. Foot anatomy, showing the joint and bones affected by hallux rigidus:

The proximal phalanx and metatarsal bone of the big toe are highlighted in yellow.

Until recently, when the arthritis in the big toe progressed to cause all movement in the joint to be painful, surgeons had only two options:

- “Cleaning out” the joint (and removing any bone spur, if present), a procedure that potentially restores some comfortable motion in the toe; or

- Fusing the bones together, thereby eliminating joint motion and the pain.

However, at HSS, some patients who might otherwise be candidates for fusion are undergoing a new surgical procedure in which a Cartiva® synthetic cartilage implant (a small amount of flexible plastic) is placed in the joint to act as a cushion between the two bones. Early results have been promising.

Metatarsalgia

Metatarsalgia is an umbrella term for pain and tenderness in the ball of the foot that occurs when the metatarsal heads become prominent and tender. The condition may be related to bunions, long metatarsal bones, arthritis or the wearing of high heels. Calluses that form under metatarsal heads are a symptom of malalignment, prominence and increased weight bearing by the structures in the foot.

Individuals with metatarsalgia and tender calluses should be evaluated and treated for any underlying conditions. Some may benefit from the use of orthotics, which can help cushion the bones of the foot to redistribute weight bearing. Cortisone injections can offer temporary symptomatic relief; but their use must be limited as the drug can cause the fat pad in the ball of the foot to atrophy, thereby worsening symptoms.

Morton’s Neuroma

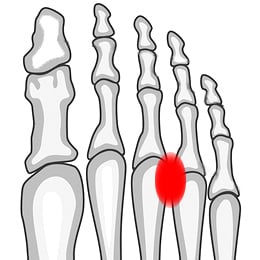

Pain in the forefoot may also be a symptom of Morton’s neuroma, a benign growth of nerve tissue (also called a pinched nerve) that usually occurs between the third and fourth metatarsal head [Figure 4].

Figure 4. Skeletal structures of the foot, showing the common location of Morton’s neuroma

In addition to tenderness and pain that radiates toward the tips of the toes, patients with Morton’s neuroma may experience numbness or the sensation that they are walking on a pebble. To distinguish metatarsalgia from Morton’s neuroma, the orthopedist checks the metatarsal bone for tenderness. If tenderness is not localized over the metatarsal head but is present between the bones, Morton’s neuroma is the likely condition. Diagnosis is confirmed with an ultrasound, which also provides information about the size and location of the neuroma.

Treatment for Morton’s neuroma can include an injection of cortisone to reduce inflammation, together with the numbing agent, lidocaine. In order to avoid atrophy of the fat pad under the ball of the foot, no more than two such injections should be administered. If pain relief is temporary, surgical removal may be recommended. “However,” Dr. Roberts notes, “if the patient does not experience any pain relief at all from the injection, we look for other problems in the surrounding structures. At this point, an MRI may provide helpful information.”

Plantar fasciitis and heel pain

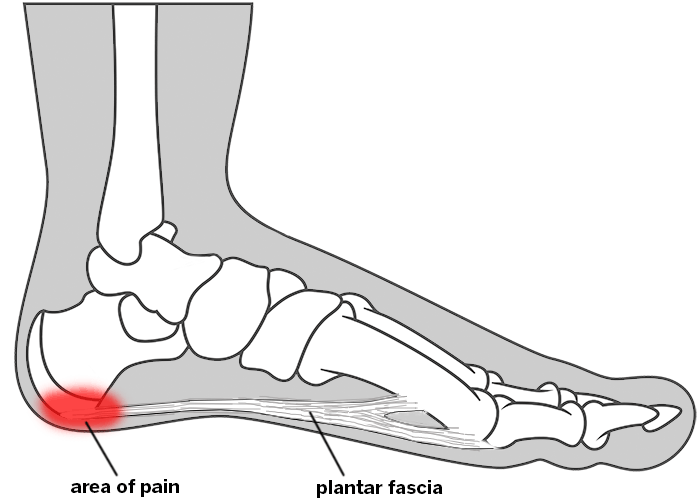

Patients seeking medical attention for heel pain often learn that they have plantar fasciitis, an inflammation of the plantar fascia, which is the ligament that connects the heel bone to base of the toes. Characterized by pain with weight bearing that is worse in the morning than later in the day, plantar fasciitis may result from chronic trauma, such as running in unsupportive shoes, or for no apparent reason. Diagnosis is based on the location of the pain: tenderness where the ligament attaches to the base of the heel [Figure 5].

Figure 5. Location of pain associated with plantar fasciitis

Orthopedists routinely order X-rays for heel pain and are careful to distinguish plantar fasciitis from stress fractures, which are also characterized by bone tenderness and pain that occurs on both sides of the heel.

“Plantar fasciitis is sometimes mistakenly called a bone spur or a heel spur, because X-rays may also show an outgrowth of bone where the plantar fascia attaches to the heel. However, heel spurs may be present in people with plantar fasciitis and those without it, and may never cause any symptoms,” says Dr. Roberts. “In fact, there is rarely any need to remove a heel spur.”

Stretching to relieve tension in the plantar fascia is the primary treatment for the condition and can include pulling back on the toes while massaging the tender area, as well as doing a “runner’s stretch” of the calf muscle, which in turn decreases tension in the fascia. Rolling a tennis or lacrosse ball, or a frozen bottle of water along the bottom of the foot may also be helpful.

In most cases, these exercises are sufficient to relieve symptoms. If they are not, use of a night splint that holds the calf in a stretched position may be recommended. Some patients may also benefit from orthotics.

At HSS, patients with plantar fasciitis that do not respond to a regimen of stretches within six months may be eligible for shock wave therapy, the same nonsurgical technology that is used to break up kidney stones. “Delivering a sound wave to the injured area promotes a healing response in up to 70% of patients who undergo the treatment,” Dr. Roberts says.

Although people with plantar fasciitis sometimes become frustrated by the length of time needed for the condition to improve, more than 95% get better without surgery. Those who continue to have symptoms may undergo procedures that reduce tension on the ligament.

Flatfoot deformity and high arches

The term “flatfoot” describes a condition in which there is no arch on the inner (medial) side of the foot; the entire sole of the foot comes in contact with the ground when the individual is standing. Children are naturally flatfooted until about the age of two or three, when the arch usually develops. (Flatfoot deformity in children becomes a concern if the foot is not flexible.) In adults who do not experience any pain associated with their flatfeet, no treatment is necessary. However, worsening of a flatfoot or a newly acquired flatfoot may signal a problem with the posterior tibial tendon (PTT), a structure that supports the arch on the inner side of the foot. This tendon may become lax, stretch and eventually rupture, resulting in flattening of the foot and ultimately complete loss of the inner or medial arch. Moreover, inflammation of the PTT can be painful. Patients with this condition are often middle-aged and may have spent lots of time walking in shoes with insufficient support.

“Early diagnosis offers the best opportunity for a good outcome,” Dr. Roberts emphasizes. “If the tendon is inflamed and painful, without deformity or collapse of the arch, we can try various measures to resolve the inflammation, including: rest, orthotics that support the arch, anti-inflammatory medications and possibly steroid injection.” If the PTT is stretched, braces or orthotics may help. However, if the arch has collapsed, resulting in persistent pain and difficulty walking, surgery to repair or reconstruct the posterior tibial tendon may be necessary.

Preserving the range of motion in the foot and restoring a more normal alignment are the goals of surgical intervention. At HSS, preoperative evaluation includes specialized X-rays that allow surgeons to measure abnormal angles between the bones of the midfoot – information that guides surgical correction. Left untreated, a damaged PTT can lead to arthritis, which may require surgery to fuse bones in the midfoot and hindfoot. This procedure is best avoided as it puts increased stress on the surrounding structures. (Read more about acquired flatfoot deformity.)

In contrast to flatfeet, some individuals have naturally high arches, a condition called cavus foot. As with flatfeet, a cavus foot does not necessarily require treatment; however, this anatomical variation can predispose a patient to other injuries. “To understand why, it’s helpful to compare the high-arched foot to a tripod in which one leg is higher than the other two and can predispose you to rolling or possibly spraining the ankle,” Dr. Roberts explains. (See more on ankle sprains below.)

Rarely, a higher arch is caused by a condition called Charcot foot. To treat this neurologic condition, which is characterized by progressive muscle imbalance and worsening of the high arch, the orthopedist may perform procedures that realign the tendons and bones to help maintain proper ankle and foot alignment.

Ankle sprains

Among the most common injuries seen by all physicians, ankle sprains occur when the foot rolls underneath the ankle or leg, resulting in various levels of injury to one or more of the ligaments that support the ankle. People sprain their ankles during activities ranging from just walking down the street to participation in high-level sports activities. Symptoms and severity of the injury vary considerably, with some patients experiencing some pain and mild swelling, and others developing grapefruit-sized swelling and an inability to place weight on the affected foot.

In the majority of cases, people who sprain their ankles can expect to recover within eight weeks, and supportive care is all that is needed to treat the injury as the ligament heals. Physicians use the abbreviation “RICE” to describe these measures: Rest, Ice, Compression and Elevation. An ACE bandage or brace may also be helpful. Patients with somewhat more severe sprains may wear a walking boot, or use crutches during recovery. In addition, those who are unable to bear weight on the foot should have an X-ray to rule out any additional injury to the ankle bones. Barring any sign of these problems, the patient is re-evaluated at six weeks. If the patient has not improved, an MRI may be ordered to assess the extent of ligament and possible ankle joint cartilage injury.

Recurrent ankle sprains can lead to chronic ankle instability and increased stress on the bones of the ankle and foot. Physical therapy to strengthen the ankle and prevent recurrence also plays an important role in recovery for anyone who has experienced two or more sprains, especially for those with more complicated sprains.

More complicated ankle sprains (those that are associated with torn ligaments, bone or cartilage injury) are more difficult to treat. Severely stretched or torn ligaments may result in chronic ankle instability. In these instances, surgical intervention may be needed to repair the damaged structures. (Read more about ankle sprains.)

High ankle sprains are a more severe, atypical form of this injury that occurs when the foot rotates externally at the time of injury. This results in injury to the ligaments that stabilize the lower leg bones above the ankle, the tibia (and the fibula (shinbones). High ankle sprains have a longer recovery period than typical sprains. (Read more about high ankle sprains.)

Ankle arthritis

In contrast to arthritis in the hip and knee, which is often the result of “wear and tear” on the joint, arthritis of the ankle is usually the result of a traumatic injury, such as a fracture. Historically, since early ankle replacements did not yield good results, effective treatment for advanced ankle arthritis was restricted to fusion of the affected area to eliminate movement in the joint and associated pain.

More recently, the standard of care for ankle arthritis has come to include promising new generations of ankle replacements that allow patients to retain motion in the joint. “So far, surgeons in the Foot and Ankle service at HSS who perform many of these replacements are seeing good short- and medium-term results thanks to improved designs,” Dr. Roberts says. “We look forward to seeing the longer-term follow-up.” Ankle replacement is not appropriate for all patients; those with advanced deformity or a history of infection are not considered for the procedure. (Read more about ankle replacement.) Another new technique under investigation at HSS for treating ankle arthritis is ankle distraction arthroplasty.

“It’s important to emphasize that the best treatment of ankle arthritis is prevention,” he adds. “This means making sure that an unstable ankle or one that has been fractured heals with an alignment that is as close to perfect as possible.”

Achilles tendon ruptures

Rupture of the Achilles tendon, which connects the calf muscles to the calcaneus (heel bone), usually occurs when the patient is playing sports, and is characterized by a sudden sharp pain, along with inability to extend the ankle and elevate up on the toes. Treatment for this injury depends on the severity of the rupture, the patient’s age and level of activity.

For non-athletes, initial immobilization of the lower leg, followed by a physical therapy program with an early focus on gentle range of motion and gradual strengthening exercises, is usually prescribed. Surgical repair of the Achilles tendon may be appropriate for younger, high-level athletes and for those whose sport requires them to jump. In patients with relatively recent injuries, skilled orthopedic surgeons can reattach the two ends of the tendon through a small incision. This procedure, which is performed routinely at HSS, often yields excellent results and is associated with a lower risk of infection and nerve injury. Following this surgery, the patient can usually begin a gradual rehabilitation program as soon as the incision is healed, which takes about 10-14 days. As with many of the conditions affecting the foot and ankle, seeking prompt medical attention for a ruptured Achilles tendon improves the patient’s chances of a full return to function.

Seeking treatment for foot and ankle problems

Because treatment of foot and ankle conditions can prove quite complicated, Dr. Roberts advises patients to seek out institutions like HSS, where orthopedic specialists have a thorough knowledge of nonsurgical treatment and appropriate surgeries, if needed, are performed frequently. The commitment to care at HSS is underscored by the hospital’s research activities, such as patient registries that track data on foot and ankle patients to determine which techniques yield the best results. This research includes important studies that seek to identify optimal perioperative care to enhance recovery, shorten hospital stays and minimize postoperative pain.

References

Summary by Nancy Novick