Horizon Extras - Spring 2008

Back in the Right Place

“We came to know my scoliosis when I was three years old because I was walking at a right angle,” says Fatima Alo, who was born in Dhaka in Bangladesh. “People would look at me differently. I was very embarrassed all the while. I always told my mother I don’t want to go to school. When I was seven years old, my parents took me to a hospital for treatment and that didn’t work out at all. After that my parents took me to many places in the city and no one could help me.”

“We came to know my scoliosis when I was three years old because I was walking at a right angle,” says Fatima Alo, who was born in Dhaka in Bangladesh. “People would look at me differently. I was very embarrassed all the while. I always told my mother I don’t want to go to school. When I was seven years old, my parents took me to a hospital for treatment and that didn’t work out at all. After that my parents took me to many places in the city and no one could help me.”

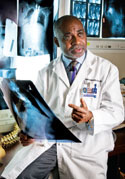

“Fatima had been ostracized because of her deformity and considered unmarriageable in her native country,” says Oheneba Boachie, MD, Chief Emeritus of Scoliosis at Hospital for Special Surgery. “She had a progressive congenital scoliosis that made breathing difficult and caused her much physical and emotional pain. And nobody wanted to treat her condition.”

"I told Dr. Boachie that back home I used to wish to come to the United States and then we got a visa for medical reasons,” says Fatima. “I think that God was helping me to find Dr. Boachie.”

Fatima came to the United States with her mother in 1991. Her back was getting much worse, and she had difficulty finding jobs. “Breathing was so difficult,” says Fatima. “I would walk one block and I had to stop. I had no hope.”

In 1993, at the age of 24, Fatima came to see Dr. Boachie. “I really got strength from him,” says Fatima. “When he was talking to me, I decided I had to do the surgery even at the risk of dying. If I didn’t do the surgery, I would be the same and die in a few years. I was willing to take the chance.”

In 1993, at the age of 24, Fatima came to see Dr. Boachie. “I really got strength from him,” says Fatima. “When he was talking to me, I decided I had to do the surgery even at the risk of dying. If I didn’t do the surgery, I would be the same and die in a few years. I was willing to take the chance.”

“Scoliosis that appears before the age of five years has a very poor respiratory prognosis,” says Dr. Boachie. “Fatima had major restrictive lung disease and her spinal deformity was so severe that her risk of paralysis with the operation was near 50 percent. We had quite a long discussion regarding the operation that we had to do, and that it was going to be very, very risky. She was very brave about it.”

Fatima’s surgical treatment was in two stages—separated by two months. In the first day-long procedure of some 14 hours, Dr. Boachie needed to remove a large section of her spine from the front through the chest. She spent the next two months in the Hospital. She was kept immobile in a halo traction to keep her head and neck stable while she battled pneumonia and coped with a tracheotomy to control her breathing. She was under constant sedation and managed by critical care specialists.

Every morning while she was in the Hospital recovering, Dr. Boachie came in to see her. “I couldn’t talk because I had a breathing tube,” says Fatima, “but he would keep paper and pencil in his pocket so I could write. After one month I was able to be upright, and I remember seeing the sky because my room was next to the river.”

The second procedure involved the removal of additional sections of spine, leaving the spinal cord to hang free without structural support while Dr. Boachie rebuilt Fatima’s spine with rods and screws. The result was a major correction of her curvature, a much more natural appearance, with barely a hint of her former deformity, and very significant health benefits.

“Patients with severe restrictive lung disease and significant spinal deformities such as Fatima’s are often not considered surgical candidates on the basis of their underlying lung disease,” notes Dr. Boachie. “However, with careful preoperative evaluation and the support of subspecialty services, surgery has successful outcomes. Having a multidisciplinary team of surgeons experienced in undertaking major spine reconstruction, anesthesiologists highly skilled in the administration of anesthesia for prolonged spine cases, as well as pulmonologists who can address breathing restrictions and pulmonary complications, are key in these types of surgeries. With Fatima, we had involvement by pulmonary, neurology, cardiology, radiology, ear, nose and throat, internal medicine, infectious disease and anesthesia specialists. She was carefully monitored and managed by a superb nursing team, and had support by nutritionists and social workers. The coordination between disciplines makes all the difference in cases as challenging as hers.”

“Patients with severe restrictive lung disease and significant spinal deformities such as Fatima’s are often not considered surgical candidates on the basis of their underlying lung disease,” notes Dr. Boachie. “However, with careful preoperative evaluation and the support of subspecialty services, surgery has successful outcomes. Having a multidisciplinary team of surgeons experienced in undertaking major spine reconstruction, anesthesiologists highly skilled in the administration of anesthesia for prolonged spine cases, as well as pulmonologists who can address breathing restrictions and pulmonary complications, are key in these types of surgeries. With Fatima, we had involvement by pulmonary, neurology, cardiology, radiology, ear, nose and throat, internal medicine, infectious disease and anesthesia specialists. She was carefully monitored and managed by a superb nursing team, and had support by nutritionists and social workers. The coordination between disciplines makes all the difference in cases as challenging as hers.”

“I just wanted to do something with my life…become a normal person,” says Fatima. “Dr. Boachie gave me a new life. I now work with the law firm of Simin H. Syed, PC. He made it possible for me to marry. He made me complete.”

An Immune System Gone Awry

In her junior year of college, Elise Rubin was accepted to study at Universite de Paris IV La Sorbonne. Less than two months into the program, she became gravely ill and nearly died from an unknown illness. When she returned home to the States, Elise learned she had systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE, or lupus), further complicated by a vascular disorder that affected circulation in her hands. Today, under the care of Jessica R. Berman, MD, rheumatologist, and Robert N. Hotchkiss, MD, orthopedic surgeon, and through her own determination, Elise is meeting the challenges of living with lupus.

Elise had signs of lupus dating back to 1999, but no one knew this at the time. In 2000, she found herself in a Paris hospital fighting for her life from a still unexplained illness. In 2001, she finally learned that lupus was the cause of her serious health problems.

Diagnosing Lupus

“A diagnosis of lupus often gets delayed because patients do not present with all the symptoms at once,” says Dr. Berman, who has been caring for Elise since 2006. “In rheumatology, the facts that you gather from the patient are sometimes more important than tests in making a diagnosis. For example, Elise’s history of swelling, fevers, and shortness of breath was initially attributed to infection. Since that wasn’t the answer, you have to entertain the diagnosis of an inflammatory condition…especially in a young woman in her 20’s or 30’s. This delay in diagnosis is unfortunately typical for lupus.”

“If the patient tells you something is wrong, there probably is,” continues Dr. Berman. “Their input is critical. I rely on Elise to tell me when she knows something is not right. She knows her body. The lab tests don’t always reflect what’s going on. While tests provide additional clues, they almost never tell you exactly what to do for the patient. I just follow those patients really closely. I think patients understand we don’t always have the answer but it is important to provide a mechanism for them to continue to be evaluated.”

Addressing the Vascular Issues of Lupus

When Dr. Berman first met Elise, she was doing fairly well in terms of joint pain and fatigue. But while these symptoms have been kept under control with immunosuppressant medications, she continues to suffer from significant Raynaud’s syndrome in which the small vessels that bring blood to the fingers spasm. To address the Raynaud’s, Elise is also on a variety of medications that are useful in relaxing blood vessels.

“We were able to control some of the symptoms,” says Dr. Berman, “but Elise’s symptoms have always been worrisome for me because some areas on her fingers are ulcerated. This is a huge concern because ulcers indicate that the blood supply has been cut off.”

“Raynaud’s causes me most of my daily discomfort and pain,” notes Elise. “I have such a severe case that essentially the tips of my fingers are open wounds.”

“Elise has very aggressive vascular issues,” says Dr. Hotchkiss, an orthopedic surgeon with particular expertise in vascular issues of the hand. “She actually had no blood flow and was at risk of losing a finger.”

Elise had an MRA – magnetic resonance angiography, which produces images of blood vessels. The MRA showed that she wasn’t getting blood flow past the middle of the hand. To address this, Dr. Hotchkiss performed a surgical procedure called sympathectomy to stop the blood vessels from constricting and increase blood flow to her fingers.

“With these types of patients and their vascular problems, it’s so important to have a good radiology department to give you the right information so you can make a decision about the surgery and the treatment,” notes Dr. Hotchkiss. “The appearance of the blood vessel can tell you a lot. Is it a blockage? Is it inflammation? Does it require surgery?”

A Multifaceted Approach to Care

Dr. Hotchkiss stresses the importance of the trust that exists among the specialties at Special Surgery. “We all work closely together to tailor the patient’s treatment to achieve an optimal outcome,” says Dr. Hotchkiss. “Our conversations involve every aspect of their care from the immune system, to the various medications they are on, to surgical treatment. In these complicated and complex patients, especially as the blood supply begins to become limited to their fingers, they require an intensive, personal, professional involvement. The value of the relationships between physicians and surgeons is very difficult to measure, but it’s not insignificant.”

“In patients with lupus,” says Dr. Berman, “you are constantly thinking about all facets of the condition and which medications address which parts of the problem—whether it is how the blood vessel reacts or whether inflammation drives the process. Little things can make a huge difference for patients. Only at a place like Special Surgery are all the resources available quickly to treat difficult patients like Elise.

“When her Raynaud’s worsened, I was able to have her see Dr. Hotchkiss right away and have the surgery. When she starts to have an inflammatory flare I can walk her over to the Hospital’s infusion room for an intravenous dose of steroids, which can calm the inflammation immediately. Every little thing that gets out of balance--if not addressed immediately—can spiral out of control for these patients.”

These resources, notes Dr. Berman, include her administrative assistant, Maricel Galindez. “Maricel is here before I am, taking calls and feeding the information to me. She’s the front line and a huge comfort to patients. They depend on her and so do I.” Patients with lupus have also found a tremendous resource in support and education programs offered by the Hospital.

“Our patients find reassurance by talking with others who have similar challenges,” says Roberta Horton, LCSW, ACSW, Director, Social Work Programs, who has led the development and implementation of these programs dating back more than two decades. Today, the Hospital offers the greatest number of support and education programs of any hospital in the country for the specialties of rheumatology and orthopedics, including several programs for patients with lupus.

“Our first program—the SLE Workshop—started in 1985 with the goal of helping not only our own patients, but also the larger community of people with lupus because it is such an incredibly complex and challenging illness,” notes Ms. Horton. “Both the disease and the treatments can have significant side effects that can effect self-esteem. Our programs enable patients to gain perspective from their peers on living with a chronic illness and the multiple issues that arise, including living with uncertainty, feelings of isolation, low self esteem and depression, role changes in family, and change in financial status—all of these can shift dramatically from the impact of a long-term illness such as lupus.”

When patients voiced interest in reaching out to each other through other means, Ms. Horton and her colleagues developed a nationwide program called LupusLine®, which is the only national telephone peer counseling service for this illness. Staffed by a social work supervisor and trained volunteers who are lupus veterans or family members, LupusLine counselors provide one-to-one support by telephone.

Charla de Lupus®, or Lupus Chat, was subsequently created for the Spanish-speaking community, offering both telephone and in-person support, followed by its Teen and Parent Lupus Chat Groups, a monthly in-person chat group for teens (14 to 18) who have lupus and their parents. LANtern®, the most recent “sister” program, was established as the only national bilingual peer health education and support program for Asian-Americans with lupus and their families. For more information on the Hospital’s lupus support programs, please visit hss.edu/lupus-programs.asp.

A Shoulder to Lean On

At first it was pain in her left shoulder that got Betsy Goff’s attention. Then she couldn’t raise her arm past a certain level. Soon she lost any rotational motion. Betsy was exhibiting the classic symptoms of frozen shoulder, and it was becoming a large problem for this college professor. Through friends, she learned of the expertise in this area of Beth Shubin Stein, MD, an orthopedic surgeon at Hospital for Special Surgery, and scheduled an appointment.

Betsy had come to the right place. Frozen shoulder has long been the subject of researchers and clinicians alike at Special Surgery. “The technical term is adhesive capsulitis,” says Dr. Shubin Stein. “It is a process of inflammation followed by a process of scarring affecting the capsule within which the shoulder lives. With frozen shoulder, the capsule becomes inflamed causing a great deal of pain—even at rest. The inflammation eventually burns itself out and the pain decreases, but patients are left with a very stiff shoulder because the capsule has thickened and is no longer elastic.”

Jo A. Hannafin, MD, PhD, Director of Orthopedic Research, began research on the condition in 1991 as an orthopedic fellow working with Russell F. Warren, MD, Surgeon-in-Chief emeritus. “Dr. Warren was performing arthroscopic surgery on patients with frozen shoulder and, upon seeing inflammation in the lining of their joint, began to biopsy this tissue,” says Dr. Hannafin. “From careful analysis of these biopsies and correlation with the clinical presentation—pain and stiffness, we gained a much better understanding of what causes a frozen shoulder.”

The Evolution of Frozen Shoulder

According to Dr. Hannafin, the condition evolves through a series of stages. The first stage is characterized by inflammation in the lining of the joint capsule. As patients move into the second stage, they have continued pain and begin to develop scarring and contracture of the capsule that surrounds the shoulder joint. If not treated, the process moves into the third stage where shoulder motion is severely limited while pain is decreased. In the final stage, motion returns slowly over a period of approximately one year.

With this understanding, Dr. Hannafin and her colleagues began to treat patients with injections of cortisone into the shoulder joint in the first two stages of the disease.

With this understanding, Dr. Hannafin and her colleagues began to treat patients with injections of cortisone into the shoulder joint in the first two stages of the disease.

“By addressing the inflammation early in the process, we discovered that you can alter the natural history of the disease,” she says. “However, many patients will arrive for treatment after this process has been going on for many months. Either their diagnosis was missed or the patient kept thinking the shoulder would get better. Some of these patients will still respond to a corticosteroid injection and physical therapy with recovery of range of motion while others will need surgery.”

Dr. Hannafin and her colleagues, including senior physical therapist Theresa Chiaia and physiatrist Jennifer Solomon, MD, continue to pursue studies of frozen shoulder. One study is evaluating the effect of injecting the shoulder with a corticosteroid under ultrasound or x-ray guidance, which allows the physician to deliver a known quantity of the steroid directly into the joint. Patients are then followed over time to evaluate response in terms of improvement in range of motion and pain reduction and the time it takes to achieve relief.

“What we learned from Dr. Hannafin’s work is that by injecting the shoulder with cortisone in the early stages, when there is still inflammation, we could halt the process from progressing and thus limit the amount of scarring,” says Dr. Shubin Stein. “If you inject the shoulder during the first stage when the condition is primarily inflammatory, then motion returns quickly with therapy. If you inject during the second stage, where there is already some scarring, it can take two to three months of physical therapy before range of motion returns.”

In the second study, physicians are performing biopsies on the capsule of patients who undergo surgery to treat the stiff and scarred shoulder. Their objective is to glean information from the biopsies that may help them to alter the natural history of frozen shoulder in other ways.

In the second study, physicians are performing biopsies on the capsule of patients who undergo surgery to treat the stiff and scarred shoulder. Their objective is to glean information from the biopsies that may help them to alter the natural history of frozen shoulder in other ways.

“Specifically, we are looking at fibroblasts, the normal cells that live in the capsule of the shoulder joint,” explains Dr. Hannafin. “Normal fibroblasts do not have the ability to contract. In frozen shoulder, we believe that the contracture of the capsule comes when the fibroblasts turn into myofibroblasts. These myofibroblasts literally begin to contract the capsule as if “shrink-wrapping” the shoulder. Something triggers those cells to go off on a pathway that is not normal for the shoulder, ultimately resulting in a frozen shoulder. We know that risk factors for developing a frozen should include being female between the ages of 40 and 60; having diabetes or thyroid disease; or undergoing radiation therapy after breast cancer, but no one is sure what the common thread is that initiates this process.”

A Case in Point

“When I first saw Betsy, she had been having increasing pain over three to four months and was told that she should have surgery for a rotator cuff problem,” says Dr. Shubin Stein. “Based on her exam and history, I felt she was in the early stages of a frozen shoulder and had been misdiagnosed as having a rotator cuff problem and could be treated for the frozen shoulder without surgery. I referred her to my colleague, Dr. Solomon, a physiatrist, who administered a cortisone injection under fluoroscopy.

It took about two weeks for Betsy’s inflammation to fully disappear,” says Dr. Shubin Stein. “She was then started on physical therapy and did wonderfully. Within three months she was pain free and had her full range of motion.”

Two years later, Betsy came to see Dr. Shubin Stein for the same symptoms in her right shoulder. “The inflammation was more stubborn and a little further along in this shoulder,” says Dr. Shubin Stein. “I again sent her to Dr. Solomon for an injection since it had worked so well on the other shoulder. The pain dissipated and Betsy started physical therapy. However, her pain returned a few months later. She had another injection followed by physical therapy. When she didn’t regain full range of motion and the pain returned yet again, we spoke about the option of addressing the problem through arthroscopic surgery. While the procedure is not indicated as frequently for this problem since the injections work so well, it can still be necessary and, when needed, patients do very well.”

Dr. Shubin Stein surgically released the contractures caused by scarring and manipulated Betsy’s shoulder to achieve full range of motion. Several weeks of physical therapy followed, and, although her range of motion was fine, a few weeks after surgery, Betsy’s shoulder was becoming painful again. “After ruling out an infection, I was concerned that she was developing a recurrent inflammation, which can occur, although rarely, after the surgery,” notes Dr. Shubin Stein.

“Dr. Shubin Stein recommended another injection, which was the magic bullet,” says Betsy. “The one-two punch of surgery and the injection addressed the pain and motion issues without question. But what Drs. Shubin Stein and Solomon provide goes beyond medicine. They take my breath away with how much time they spend with patients and how much they care.”

“The nice thing about Special Surgery is that it has all of the subspecialties under one roof,” says Dr. Shubin Stein. “I know the problems, my associates know the problems, and together with the physical therapists, who play a huge role, we do the right thing by the patient.”