Revision Surgery for Scoliosis, Kyphosis and Other Spinal Deformity

When patients with spinal deformities such as scoliosis and kyphosis are carefully screened and prepared, surgical treatment results in significant relief of pain and fatigue, as well as cosmetic improvement. But in a small number of cases, additional intervention (revision spine surgery) may be necessary.

When do you need a second spine surgery for scoliosis or kyphosis?

Patients with spinal deformities that progress, whose symptoms persist or worsen despite surgery, or who develop new or different symptoms, require careful evaluation. Whenever possible, patients are treated nonsurgically, but in some instances, revision surgery is recommended. This can include patients who develop pseudarthrosis or conditions that affect the spinal discs, nerves or vertebrae and which contribute to the progression of their spinal deformity.

For many patients with scoliosis or kyphosis, the goal of the first surgery is to create a fusion (essentially a welding together of the vertebrae) in the affected area. In order to promote healing and maintain alignment, fusions are secured with instrumentation. This can include rods, hooks, screws, or cages. When one or more of these measures fail, leading to pseudarthrosis (failure of the bone to heal properly following fusion surgery) revision surgery may be necessary. This and other conditions may contribute to progressive deformity developing above or below the surgical site, as the non-fused vertebrae respond to additional forces being placed upon them. In addition, discs in the spine may become compressed or slip out of place, resulting in conditions such as disc herniations, degenerative disc disease, and spondylolisthesis.

Other reasons revision surgery may be necessary include:

- Instrumentation that has loosened or pulled away from the bone

- Radiculopathy, or nerve pain associated with acute nerve compression in the spine, either from parts of the spine (disc, ligament, or bone) or from the previously placed implants

- Stenosis, or leg heaviness and walking limitation associated with chronic nerve compression in the spine, typically from disc degeneration, ligament hypertrophy, and bone spur formation

- Infection in the bone or around the instrumentation

- The presence of bursas (fluid-filled sacs) that have formed around the instrumentation used for fusion

- Arthritis that develops as a result of accelerated wear and tear on the spine after fusion

- Poor bone quality, such as osteoporosis or osteomalacia, that can predispose to bone/implant fixation failure or fractures in the spine bones, either within the fused segment or external to the operated region

Achieving a thorough understanding of the patient’s condition prior to the initial surgery – as well as the nature of the surgery, and how they have been symptomatic following their initial surgery – helps guide the orthopedist’s treatment recommendations. Expertly-performed prior surgery can unfortunately still fail, so we need to know why the first procedure didn’t work and what can be done now to improve the patient’s symptoms.

Symptoms that indicate and evaluation for revision spine surgery

In addition to pain and fatigue, a small number of patients may seek medical care when they develop altered trunk position (termed “loss of balance”) following surgery to correct spinal deformity. This may be experienced as a feeling of falling forward, a condition called sagittal decompensation (or flatback), or of falling off to one side, a condition called coronal decompensation. Flatback has been associated with Harrington rods, which were used for several decades to correct scoliosis curves and sometimes had the effect of eliminating too much of the natural “sway” in the lumbar spine.

Patients may also seek medical advice because they feel that their spinal deformity is progressing, that their clothes are fitting differently, or due to a perceived height change.

The type and site of pain the patient experiences, as well as the time when symptoms develop, all provide clues to the underlying medical issues. For example, patients who develop pseudarthrosis typically complain of activity-related pains that are “aching and dull” in character, that may be described as a severe “bruise,” and are worsened with tasks that promote movement in the area of the pseudarthrosis (bending, lifting, twisting). A patient who has severe “electrical and burning” back and leg pain on standing, or specific weakness in the leg muscles, is likely to have a neurological problem, such as a nerve root that is being compressed.

Those with back pain above or below the site of a fusion that is activity-related and classically worse at the end of the day may be experiencing muscular symptoms, as the back muscles following a fusion are required to control long segments of the spine rather than individual vertebral bones, requiring higher forces to be generated, and expected strain and fatigue symptoms if muscle power is insufficient.

Neurological pain symptoms that occur immediately after surgery raise questions about the placement of screws, or persistent pressure on a nerve root or the spinal cord. Pain that occurs some time after surgery may be a sign of degeneration/arthritis, or an infection, possibly one that started elsewhere in the body that migrated to the tissue surrounding a metal implant.

Imaging and diagnosis for revision spinal surgery

Imaging techniques used to assess patients with the symptoms listed above include the following:

- Standing orthogonal X-rays, oblique views, and dynamic studies (the patients is asked to bend side to side or back and forth) can help determine the presence of bone spurs, instability, or uncommon fractures.

- CT scans provide highly detailed 3D information about the spine bones and can accurately show the position of instrumentation in the bone.

- A CT myelogram (a CT scan in which dye is injected into the spinal canal that allows the nerves to be seen) can show if pain is related to a pinched or inflamed nerve.

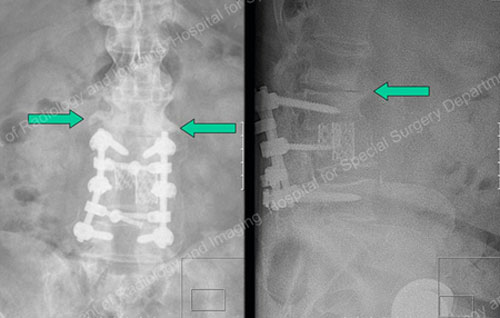

Figures 1 & 2: X-rays showing bone spurs (as marked by arrows) adjacent to prior fusion.

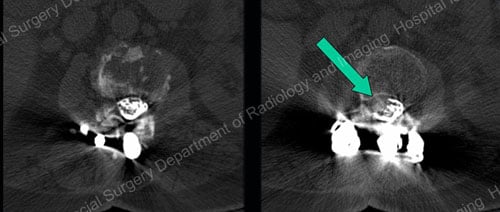

Figure 3: CT Scan of a bursa from instrumentation. The arrow points to a bursa below the screws (which appear as bright white spots near the bottom of the pictured bone). The bursa is a lighter gray followed by a dark gray band (subcutaneous fat), then a very light gray (superficial skin) and then black (air outside the patient and background from the circle of the image frame).

Figures 4 & 5: CT myelograms showing normal (left) and pinched (right) nerves. On the right, an arrow points to a mass in the central spinal canal column pinching the Cauda Equina nerves on the right side.

When is revision spinal surgery not required?

Muscle pain and fatigue that follows spinal surgery often resolves over time and can be addressed with a range of measures including activity modification, physical therapy, moist heat, massage, and acupuncture. Chiropractic care may also be effective in limiting muscular symptoms and can be added to the above measures.

If physical therapy and other non-drug interventions are ineffective, oral medications such as NSAIDs (nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs) or a steroid injection that will reduce inflammation may be helpful. Opioid medications may also be recommended for pain relief in some situations but are used very sparingly.

If there is a minor problem in a post-op patient, it gets a “minor” solution. Patients may eventually require a revision, but they are best managed nonsurgically until they need the revision done. While arthritis is usually treated nonsurgically initially, severe arthritis may also require surgery. Infections, he adds, should always be aggressively managed.

Surgical treatment

Revision surgery for spinal deformity may involve one or more procedures to address the individual patient’s symptoms and/or progression. The patient’s overall health also guides the orthopedic surgeon’s treatment recommendations. The following are just a few of the scenarios that may be considered:

- Extension of a previous fusion proximally or distally to address degenerative changes above or below the original fusion

- Placement of additional instrumentation; for example, as in patients with pseudarthrosis in whom the initial correction and fusion was performed using only a posterior approach (from the back). In revision surgery, an anterior approach (from the front), and placement of additional instrumentation to create a fusion on the other side of the spine can result in a successful fusion and elimination of instability in the spine.

- Osteotomies, procedures in which intentional fractures are made in the affected bone or bones to arrest progressive deformity and restore proper alignment.

- Removal (and possibly replacement) of instrumentation in patients with pain and/or infection associated with these implants.

- Irrigation and debridement – removal of infected tissue – and antibiotic therapy in the presence of infection.

- Decompression – a surgery to relieve stenosis, or “pinching” of nerves, by removing the tissue that is pressing on a nerve or nerves.

Cosmetic concerns alone – if the patient is unhappy with their appearance, but has no pain or progression of the deformity – are not a common reason for revision surgery. However, when progression is demonstrated, even in the absence of pain, surgery may need to be performed to add additional fusion levels and control the progression. In other cases, the placement of additional instrumentation to support the vertebrae may address the underlying problem, and arrest the progression without additional fused levels.

Treatment outcomes

While excellent results can be achieved with revision surgery, especially when patients receive care from a highly experienced multidisciplinary team, the likelihood of effective symptom control does diminish with each successive revision surgery. Moreover, revision surgeries are associated with a higher risk of complications. Patients who undergo revision surgery primarily to address deformity, and/or to correct spinal coronal/sagittal balance, will most likely see some improvement.

The degree to which pain relief can be achieved with revision surgery is somewhat harder to anticipate. Overall, the best results from revision surgeries are usually seen in patients with radiculopathy or stenosis symptoms in the legs that is treated surgically with decompression surgery.

Relief of back pain symptoms varies; however, patients with more severe pain appear to show the most marked improvement.

Future directions in spinal revision surgery

In order to continue improving outcomes in treatment, HSS spinal surgeons are also looking at ways to optimize bone tissue formation, remodeling, and growth. Substances called bone morphogenic proteins (BMPs) help build stronger bone and have been widely used to promote better success and stronger spinal fusions.

In addition, ensuring that patients are not Vitamin D and/or calcium deficient may improve their “bone health”, thereby strengthening their bone and improving their ability to tolerate the insertion of rods, screws, and other instrumentation, as needed.

Finally, research in the field is focusing on surgical techniques that are minimally invasive, a development that would – in some cases – allow surgeons to perform procedures using an incision of one to two inches in length instead of prior techniques that required much longer incisions. This trend towards minimally invasive techniques is expected to not only minimize soft tissue trauma, but to be better tolerated by patients and allow them to become mobile again more quickly following surgery.

This makes good sense for patients who require short fusions. However, for those who require more extensive surgeries involving decompressions and fusions, traditional approaches are more appropriate.