The Opioid Epidemic: An Update on Opiate Misuse and Current Strategies for the Healthcare Team

At the invitation of the Social Work Staff Development Committee of the HSS Department of Social Work Programs, Dr. Avery spoke before an audience of HSS social workers and invited clinical professionals. The presentation was designed to help social workers and other clinicians better understand and respond to the opioid epidemic for the benefit of patients and their families.

Jonathan Avery, MD, speaking at HSS.

The original presentation has been supplemented with content provided by the HSS Department of Anesthesiology, Critical Care & Pain Management.

Objectives

- Define what opioids are.

- Describe the current opioid epidemic.

- Discuss the differences between opioid misuse and the misuse of other substances.

- Help audience understand treatment options for opioid use disorder.

- Discuss strategies and assessment tools to address opioid issues in collaboration with the healthcare team.

- Provide additional resources for healthcare professionals.

Opioids

- Naturally or synthetically created substance that acts on the opioid receptors, which are primarily located in the central nervous system and gastrointestinal tract but also in peripheral tissues.

- Opioid receptors control response to pain, stress, mood, reward and motivation.

- Examples include heroin, opium, endorphin, morphine, codeine, fentanyl, oxycodone, methadone, hydromorphone, oxymorphone and hydrocodone.

- They are used most often to treat pain for a short period of time.

Patient case examples

A patient is prescribed opioids by another provider (e.g., a prior MD or outside MD). The patient’s current MD does not want to continue to prescribe medication, but patient sees this as the only acceptable/effective treatment.

- A patient with depression/anxiety has been on high-dose opioids for 10 years, which were prescribed in the past. Current MD would like to stop prescribing opioids. The patient agrees to visit detox centers but does not pursue treatment; in conversations with MD, the patient is open to tapering off but is very anxious about it.

- A patient sustained a severe right brachial plexus injury from a motorcycle accident. After the incident, the patient received IV opioids for three out of four weeks of a hospital stay, then, upon discharge, transitioned to pills. Patient was insightful about addiction to opioids, stopped cold turkey and now treats withdrawal symptoms with daily marijuana use.

Attitudes toward people with co-occurring mental illness and substance use disorders (dual diagnosis)

Treating opioid use is different than that for any other substance. It’s hard to treat addiction, however, outcomes are good with more than 24 million in recovery. There is a lot of stigma and bias associated with treating people with substance use disorders (SUDs), which results from common perceptions that people with such disorders have a “moral failing.” Working in hospitals, we are less likely to see those in recovery, however, it is important to see that people can get better and to hold onto a positive image of recovery. It is also important to carefully consider how we describe the person and to avoid using shaming words, e.g., “clean” and “dirty.” (Read more about this at SubstanceUseStigma.com.)

Implicit bias

Similar to countertransference or the automatic and unconscious ways that we judge a person, it is important that we not allow the above-mentioned stigmas or prejudices affect or direct the professional service we provide to patients. Opioid use is neither “good” nor “bad.”

Implicit bias is a term that refers to the relatively unconscious and automatic human features of prejudiced judgment and social behavior.

While psychologists in the field of “implicit social cognition” study “implicit attitudes” toward consumer products, self-esteem, food, alcohol, political values and more, the most striking and well-known research has focused on implicit attitudes toward members of socially stigmatized groups, such as individuals with SUDs, African-Americans, women and members of the LGBTQ community.

History of pain treatment – Opioids are bad, opioids are good

The perception of opioids as being “bad” or “good” – by lawmakers, medical professionals and society more generally – has fluctuated significantly over the past century.

"Bad”

- 1914 – The Harrison Narcotics Tax Act

- 1965 – Methadone Maintenance

- Current “Opioid Epidemic”

“Good”

- 1965 – Methadone maintenance

- 1990s – Pain as a “fifth vital sign” (This resulted in a move to increase opioid use for chronic pain with the incorrect assumption that there is low risk for addiction.)

Since the 1960s, methadone maintenance has been demonstrated to have very good outcomes, however there is a lot of stigma attached to this practice, and it is underutilized by the hospital system.

Adolescents are using more opioids through “pill parties” and can get them online or by stealing them from family and friends. According to a data brief released in December 2017 by the National Center for Health Statistics, there was a fourfold increase in opioid deaths among 15- to 24-year-olds between 1999 and 2016.

Drugs involved in US overdose deaths include common prescription opioids such as oxycodone and hydrocodone, as well as fentanyl and heroin. Deaths involving synthetic opioids, in particular, are on the rise. Between 2020 and 2021, the rate of drug overdose deaths involving synthetic opioids other than methadone increased 22%, while those involving heroin declined 32%. Drugs kill more people in the US than do cars or guns. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimated that an average of 292 Americans died from drug overdoses in the United States each day during 2021, with more than 75% of those resulting from opioids.

There is also a hidden epidemic emerging in conjunction with the combination of benzodiazepines and opioids. Benzodiazepines such as alprazolam (Xanax), clonazepam (Klonopin) and diazepam (Valium) increase the high when combined with an opioid. Patients also put themselves at risk by combining opioids with nonbenzodiazepine sleep aids such as zolpidem (Ambien).

It’s complicated

When using opioids, the dopamine levels in the brain spike and the brain is rewired and motivated to increase use. Not everyone who uses opioids will develop a SUD, however some may have a genetic predisposition, and it is more complicated when pain, isolation and trauma is involved. Opioids may help in the right circumstances, such as for acute pain (e.g., after surgery), cancer-related pain, as an end-of-life treatment or when other treatment modalities have proven inadequate, but they are not useful or appropriate for treating non-cancer-related, long-term chronic pain.

Substance use disorder

- SUD is a cluster of cognitive, behavioral and physiological symptoms that indicate that the individual continues using the substance despite significant substance-related problems. (See also, Opioids: Understanding Addiction Versus Dependence.)

Pseudoaddiction

- Behaviors that look addictive but do not reflect true addiction. In such cases, a patient experiencing pain typically seeks higher doses of a medication, or additional medications because the prescribed treatment is not adequately alleviating the pain.

Hyperalgesia

- Hyperalgesia is an increased sensitivity to pain.

- It can be difficult to distinguish from tolerance, since the increased sensitivity is often compensated for by escalating the dose of the opioid. This can lead the patient to experience no increase in pain control or to possibly experience even worse pain. Hyperalgesia can occur relatively quickly or over time through chronic opioid use (known as opioid-induced hyperalgesia).

CDC recommendations for acute pain

- Patients who are prescribed opioids for acute pain are more likely to use opioids long-term, and a greater amount of early opioid exposure (taking opioids for a longer time or at higher doses) is associated with greater risk for long-term use.

- The CDC Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain recommends that if opioids are needed in cases of acute pain not related to a major surgery or trauma (e.g., acute back pain, sprained ankle, etc.), use for less than three days will often be sufficient – unless circumstances clearly warrant additional opioid therapy – and that use for more than seven days will rarely be needed.

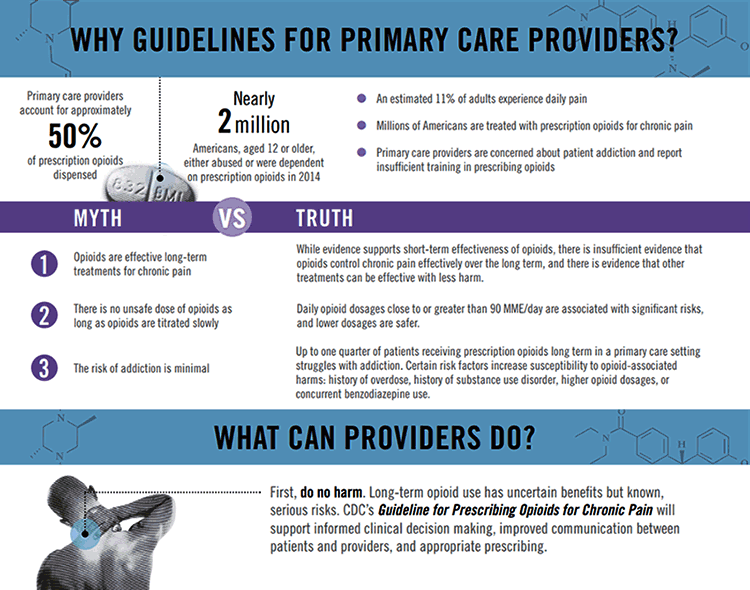

Why Guidelines for Primary Care Providers,Courtesy of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

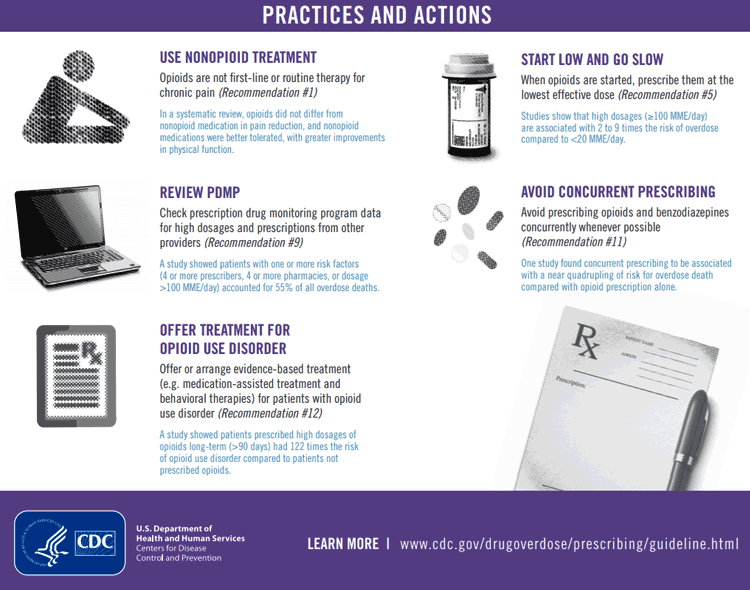

Practices and Actions, Courtesy of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

Prevention

- Take a full substance use history and assume the patient is using. During every visit, ask:

- “How much do you use?”

- “When was the last time you used?”

- “What types of opiate medications do you have at home?”

- Urine screens should be part of treatment.

- Always check ISTOP

- Involve the family and other providers.

- Use evidence-based screening tools:

- SISAP (Screening Instrument for Substance Abuse Potential)

- SOAPP (Screener and Opioid Assessment of Patients in Pain)

- Opioid Risk Tool

- Current Opioid Misuse Measure

- Don’t judge the patient.

- Use motivational tools.

Risk factors for opioid misuse

- Personal and family history of substance use disorders

- Heavy tobacco use

- Mental illness

- Legal history

- Trauma

- Young age

Indicators of misuse in pain patients

- Frequent problems with medications (losing medications, early renewal, etc.)

- Appearing intoxicated or sedated

- Not agreeing to non-opioid medications

It is important to set up expectations from the beginning of treatment (e.g., no early refills) and to provide a pain contract. A goal should be set for how long opioids will be used and, if they are not helping after a prescribed period, other alternatives should be used to treat pain.

Address co-occurring disorders

- High rates of depression, anxiety disorders, PTSD, substance use disorders, personality disorders in individuals with pain

- Psychological components of pain: hopelessness, loss of control, etc.

- Evidence-based psychopharm, CBT, biofeedback, exercise

- High rates of depression AKA "major depressive disorder" or MDD (33% to 54%, depending on the study), anxiety disorders (16.5% to 50%), PTSD (up to 50% in veterans), substance use disorders (15% to 28%, depending on the study), personality disorders (31% to 81%, depending on the study) in individuals with pain

- Compared to pain patients without MDD, patients with co-morbid MDD and chronic pain had:

- Poor quality of life, greater pain severity, higher prevalence of pain

- Most anxiety disorders occur before pain onset

- Most depressive disorders appear after onset of pain

- The biopsychosocial model for chronic pain management includes: evidence-based pharmacotherapy, CBT or other therapies (biofeedback/relaxation, dynamic) emphasizing chronic pain self-management

Safe storage and disposal of opioids – AMA guidelines

- Talk to patients:

- More than 70% who misuse opioids receive them from family friends.

- Remind patients:

- Store opioids in a safe place – preferably locked.

- Discuss risks to household members.

- Urge patients to dispose of unused medications using:

- Local “take back” or mail-back programs.

- Drop box at a local police station.

- DEA-authorized collection site.

- Pharmacy collection points.

Treatment

For any substance use disorder there are many non-medication forms of treatment, e.g., AA (Alcoholics Anonymous), SMART, Mutual Help for Addiction Recovery, DBT (dialectical behavior therapy), mindfulness techniques and cognitive behavioral therapy, and motivational interviewing. The use of motivational interviewing is a big change in treating addiction. It is mostly driven by the patient by meeting each patient where he or she is rather than at a predefined start point. First, begin by assessing what the patient likes about the drugs: Ask questions in a nonjudgmental way to assess the patient’s readiness and move forward when there is an opening for change (with the goal being to have a “change talk”). Ask for permission to suggest treatment options and give advice. Then the patient will feel part of the conversation, and the spirit is to connect with people and find out what they want.

Opioid use disorder treatment outcomes*

- Short-term detox is almost never successful (relapse rates approach 95%).

- Buprenorphine and methadone are the gold standards. The use of either is shown to:

- Decrease opioid use, overdose risk, mortality, IV drug use and associated diseases, and crime.

- Increase employment, family stability, pregnancy outcomes.

- Long-acting injectable naltrexone.

* Bentzley BS et al. 2015; Kreek MJ et al.,1996; 2000, 2001; 2003; 2010; Weiss et al., 2015.

Medication-assisted therapy

- Providers Clinical Support System for Medication Assisted Treatment

- Eight-hour waiver training for buprenorphine

- Webinars and modules on EVERYTHING addiction

- Mentors

- AAAP or ASAM

- SAMHSA and their medication-assisted treatment app

- HealingNYC

Who should discontinue opioids?

- Almost everyone!

- And especially:

- noncompliant patients

- those with dose escalation

- patients with a questionable pain diagnosis

- patients with high pain scores despite use of opioids

- people presenting to your practice for the first time on opioids

- young patients

- patients involved with a long-term opioid trial without a trial off opioids

Strategies to reduce

Methadone

- Full mu opioid agonist with long half-life

- QTc prolongation

- Respiratory depression can occur at any dose

- Daily dosing at methadone clinics

- Rapid dose titration is dangerous:

- Large volume of distribution

- Unpredictable pharmacokinetics

- Duration of analgesia is 4 to 8 hours (single-dose studies) to start, increasing to 22 to 48 hours with repeated doses

Buprenorphine

- Partial opioid agonist

- Has antidepressant properties

- Ceiling effect

- Administered alone or in combination with opioid antagonist naloxone

- Office based, schedule III

- It can take up to two years for the brain to rewire and reset.

- Retention to the program is good, with 50% of patients staying on it

How to choose?

- May benefit more from methadone clinic:

- Long history of opioid use disorder

- IV use

- Use of high dose opioids

- Respond to structure

- May benefit more from buprenorphine:

- Strong support system/structure already in place

- Unable to participate in methadone clinic due to work/travel

Naltrexone (Vivitrol or ReVia)

Patients taking this opiate-blocking medication, cannot be on any other opioids. They must also be detoxed. This is a good option for highly motivated people.

- Extended release

- Mu opioid antagonist

- Blocks euphoric effect of mu opioids

- Monthly, IM injection

- 7 to 10 days without opioids

- Can be burdensome for providers

- Less stigma

- Expensive – $1500 per injection

Graphic by Jonathan Avery, MD

Naloxone hydrochloride rescue kits

The New York City Health Commissioner’s standing order has been revised to include the single-step, FDA-approved intranasal naloxone HCl (Narcan) product and there are more than 730 pharmacies across NYC where anyone can walk in and obtain this or another naloxone product without a prescription.

For patients with insurance, they will pay a copay (Medicaid copays are usually a $1), but may not have a choice in which formulation they receive. For patients without insurance, paying out of pocket varies based on formulation.

Medical marijuana

- In December 2016, New York State Department of Health (NYSDOH) announced that chronic pain would be added as qualifying condition for medical marijuana in December 2016. In July of 2018, the department added opioid replacement as a qualifying condition for medical marijuana. (Read here for Connecticut and New Jersey regulations and qualifying conditions.)

- The annual rate of opioid overdose deaths decreased substantially – by 25% on average – following the passage of medical marijuana laws, compared to states that still had bans.

- Rates of opioid prescriptions went down in states that implemented laws allowing access to medical marijuana.

- Marijuana use disorder has been linked to numerous other negative health consequences independent of opioids.

Conclusion

There has been a culture change with regard to how we treat opioid use and under what circumstances we provide options for treatment. The general approach is to slowly taper and discuss this at every medical visit. It might not be a problem today, but eventually external factors or comorbidities can have ill effects on the person. The anticipatory anxiety and fear of reduction is greater than the process. Go for the early win by reducing small doses over time and then increase the taper. Meet patients where they are – at whatever level they are prepared to accept treatment and advice. Always provide options and resources, and don’t rush it.

References

Original presentation: October 16, 2017

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

Substance use resources for professionals and patients

We hope that you find these resources helpful; they are provided for informational purposes only and are not intended to comprise a complete list. Links to sites are not meant as endorsements or recommendations by HSS or its faculty.

Buprenorphine training

- Providers Clinical Support System

“PCSS provides evidence-based training and resources to give healthcare providers the knowledge they need for treating OUD (opioid use disorder).”

Naloxone rescue kits (Narcan)

Pharmacy information: Send patients to a nearby pharmacy that is dispensing naloxone under the New York City Health Commissioner’s standing order, or write prescriptions for naloxone. The Health Commissioner’s standing order has been revised to include the single-step, FDA-approved intranasal Narcan product, and there are over 730 pharmacies across the city where anyone can walk in and obtain this or another naloxone product without a prescription. You can find a nearby participating pharmacy by using their pharmacy locator. (Expand the "Drug and Alcohol Services" menu and select "Naloxone in pharmacies.") For patients with insurance, they will pay a copay (Medicaid co-pays are usually a $1), but may not have a choice in which formulation they receive. For patients without insurance, paying out of pocket varies based on formulation.

Outpatient pain/addiction (insurance accepted)

- Midtown Center for Treatment and Research (Weill Cornell Medicine)

- New York’s Parallax Center

- North American Partners in Pain Management, Syosset, NY, (516) 496-6447

Outpatient pain/addiction (private pay)

- Compass Health Group

- Edwin A. Salsitz, MD, Internist, ASAM

212.420.4400 or esalsitz@chpnet.org

Inpatient treatment (insurance accepted)

Inpatient treatment (private pay)

Additional substance use treatment resources

Prepared by Mavis Seehaus, MS, LCSW

Director, Ambulatory Care Social Work Services

Department of Social Work Programs

Hospital for Special Surgery

Addiction Institute at Mount Sinai – Beth Israel (Medicaid, commercial insurance)

First Avenue at 16th Street

New York, NY 10003

212.420.4220

Addiction Institute at Mount Sinai – West (Medicaid, commercial insurance)

1000 Tenth Avenue

New York, NY 10019

212.523.6491

Bellevue Hospital (Medicaid, commercial insurance)

461 First Avenue

New York, NY 10016

212.562.4141

Hazelden (Commercial insurance only)

322 Eighth Avenue

New York, NY 10001

212.420.9522

Inter-Care (Medicaid, commercial insurance)

51 East 25th Street

New York, NY 10010

212.532.0303

NYC Health, Drug and Alcohol Use Services

Realization Center (Medicaid, commercial insurance)

- 19 Union Square West, 7th Floor (Pvt. Entrance 25 East 15th Street)

New York, NY 10003

212.627.9600 - 175 Remsen Street

Brooklyn, New York, 11201

718.342.6700

Substance Treatment and Research Service of Columbia University (STARS)

(Free and confidential treatment of substance abuse in the context of a research treatment clinical trial)

3 Columbus Circle, suite 1408, 14th Floor

New York, NY 10019

(Located between 57th and 58th St.)

212.923.3031

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5), American Psychiatric Association, Arlington 2013.

- Bachhuber MA, Saloner B, Cunningham CO, Barry CL. Medical Cannabis laws and opioid analgesic overdose mortality in the US, 1999-2010. JAMA Intern Med 2014; 174:1668-73.

- Bentzley BS, Barth KS, Back SE, Book SW. Discontinuation of buprenorphine maintenance therapy: perspectives and outcomes. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2015 May;52:48-57.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. Drug Overdose Deaths. https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/deaths/index.html. Last reviewed August 22, 2023. Accessed December 20, 2023.

- Johnston LD, Miech RA, O'Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE. (December 16, 2015). "Use of ecstasy, heroin, synthetic marijuana, alcohol, cigarettes declined among US teens in 2015." University of Michigan News Service: Ann Arbor, MI. Retrieved from http://www.monitoringthefuture.org.

- Kreek MJ. Opiates, opioids and addiction. Mol Psychiatry. 1996 Jul;1(3):232-54.

- Kreek MJ. Methadone-related opioid agonist pharmacotherapy for heroin addiction. History, recent molecular and neurochemical research and future in mainstream medicine. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2000;909:186-216.

- Kreek MJ. Drug addictions. Molecular and cellular endpoints. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2001 Jun;937:27-49.

- Kreek MJ, Borg L, Ducat E, Ray B. Pharmacotherapy in the treatment of addiction: methadone. J Addict Dis. 2010 Apr;29(2):200-16.

- Leibschutz JM, Saitz R, Weiss RD, Averbuch T, Schwartz S, Meltzer EC, Claggett-Borne E, Cabral H, Samet JH. Clinical factors associated with prescription drug use disorder in urban primary care patients with chronic pain. J Pain 2010;11:1047-55.

- Ries RK, Fiellin DA, Miller SC, Saitz R (Eds.). The ASAM Principles of Addiction Medicine, Fifth Edition. Wolters Kluwer, Philadelphia 2014.

- Volkow ND, Baler RD, Compton WM, Weiss SRB. Adverse health effects of marijuana use. N Engl J Med 2014;370:2219-27.

- Weiss RD, Potter JS, Griffin ML, Provost SE, Fitzmaurice GM, McDermott KA, Srisarajivakul EN, Dodd DR, Dreifuss JA, McHugh RK, Carroll KM. Long-term outcomes from the National Drug Abuse Treatment Clinical Trials Network Prescription Opioid Addiction Treatment Study. Drug Alcohol Depend 2015; 1;150:112-9.