Brachial Plexus Injury

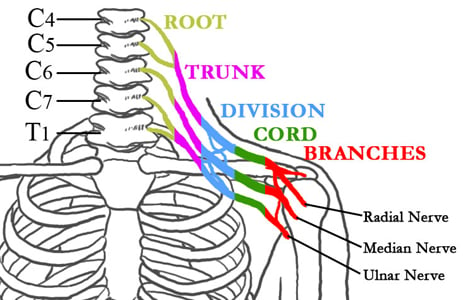

The brachial plexus refers to a complex web of large nerves that exit from the spinal cord in the neck and direct the movement and sensation of the entire upper limb.

Figure 1: The nerves of the brachial plexus in relation to the spine, ribcage, shoulder, and arm

Traumatic brachial plexus injuries, which are most commonly sustained in high speed motor vehicle accidents or while engaged in sporting events, affect the sensibility and muscle power in part of or the entire limb. Approximately 15% of brachial plexus injuries have an injury to the blood supply of the arm as well, and emergency surgery may be indicated.

The extent of spontaneous nerve recovery is unpredictable and generally imperfect. Frequent and thorough examination over the first three to six months following injury is necessary to document signs of nerve recovery, and additional imaging (such as MR neurography) or electrodiagnostic tests are often required. HSS is home to the Center for Brachial Plexus and Traumatic Nerve Injury, a nationally recognized resource for patients of all ages, providing diagnostic and reconstructive options for patients with injuries to – or dysfunction of – the peripheral nerve and brachial plexus.

One form of brachial plexus injury, often called Erb's palsy or Erb-Duchenne palsy, causes loss of sensation or paralysis in the upper arm. This injury usually affects infants during a difficult childbirth, however, it can also happen at any age after a trauma to the head and shoulder. In both cases, the head and neck are forcefully bent sideways, damaging the C5-C6 nerves of the upper trunk.