Femoral Osteotomy Surgery for Hip Conditions

Proximal femoral osteotomy is a surgical procedure that is performed to correct specific deformities of the femur – the long bone in the upper leg – and the hip joint. Orthopedic surgeons perform the operation, which involves cutting the bone, in order to realign it and restore a more normal anatomy, thereby addressing or preventing problems related to the deformity. These problems may include articular cartilage damage in the hip joint, tears to the labrum (the crescent-shaped cartilage structure that runs along the rim of the hip socket) and various forms of hip impingement – abnormal contact between the two bones that meet in the hip joint.

To better understand these deformities, it's helpful to consider the normal hip. This "ball and socket" joint is located where the thigh bone (femur) meets the pelvic bone. The femur is the largest bone in the body and provides the essential joint connection to the body, as well as support and alignment of the leg. The upper segment of the femur, the femoral neck, curves and angles forward toward the pelvis. At the top of the femur is the femoral head that fits inside the cavity in the pelvic bone that forms the socket, also known as the acetabulum; together forming the hip joint. The surfaces of the joint are covered with a smooth, cushioning layer called articular cartilage. The articular cartilage is what absorbs the load and allows the bones to glide smoothly. As shown, in the healthy hip, there is a perfect fit and the head of the femur positions securely in the acetabulum.[Figure 1]

Figure 1: Normal anatomy of the femur and hip joint.

The angle of the femoral neck to the shaft of the femur is called version. This can be considered to be the "twist" or "torsion" of the femur bone. Normal version is a forward angle of 12 to 15 degrees (12° to 15°). In individuals with version deformities, the femoral neck may be rotated either too far forward - a condition called excessive anteversion, or too far backward, which is called retroversion. Both of these conditions result in the ball portion of the hip joint being situated at an unhealthy angle to the cup portion of the socket and can lead to damage to the hip joint surfaces and surrounding structures.[Figure 2]

Figure 2A*: Left hip viewed from above. Normal femoral anteversion, which is approximately 15°.

Figure 2B*: Excessive femoral anteversion;

On the left; position of the anteverted femoral head with the foot straight.

In this position, the head subluxes out the front of the joint.

On the right; most patients with hip anteversion compensate by walking with an in-toeing gait to

better contain the femoral head within the acetabulum and to minimize pain.

Figure 2C*: Excessive Femoral retroversion;

On the left; position of the retroverted femoral head with the foot straight.

In this position, the neck of the femur impinges on the front of the acetabulum.

On the right; most patients with hip retroversion compensate by walking with an out-toeing

gait to avoid hip impingement and pain.

A person with excessive hip anteversion, in order to maintain a more stable hip joint position, will instinctively tend to walk with the toes pointed in toward the middle of the body ("in-toeing"). People with excessive hip anteversion not only have discomfort in the hip, but are at risk for tears of the labrum and developing arthritis as the cartilage that lines the joint is damaged.

People with retroverted femurs tend to walk with their feet turned out ("out-toeing"). As a result of abnormal alignment of the femoral head in the acetabulum there is increased impingement at the margins of the joint during hip movement. In some cases a ridge or spur of extra bone may be present which restricts or blocks normal hip joint motion. When this condition – also known as hip impingement, femoroacetabular impingement or FAI – occurs due to a ridge of excess bone on the femoral neck, it is known as cam impingement; if the ridge of bone develops along the rim of the socket or acetabulum, the condition is called pincer impingement.

In some cases, the patient may also have an abnormality in the hip socket or acetabulum, The acetabulum can also be excessively anteverted, a condition that makes the hip quite unstable and at risk of dislocating, or retroverted, causing impingement.

Abnormalities of the angle between the femoral neck and shaft of the femur may also require surgical correction. A decreased neck-shaft angle is called coxa vara or varus alignment. An increased neck-shaft angle is called coxa valga or valgus alignment.[Figure 3] These aberrations may also cause hip pain and degeneration.

Figure 3: The Femoral Neck-Shaft Angle;

3A: Normal femoral neck/shaft angle;

3B: Coxa Valga: Increased femoral neck/shaft angle;

3C: Coxa Vara: Decreased neck/shaft angle.

Rotational or version abnormalities, as well as coxa vara and coxa valga occur more commonly in women than men and may be present at birth, or may develop by the time of skeletal maturity. Often, these deformities are present in both legs. However, they may also result from a traumatic injury or fracture of the femur, such as those suffered in a motor vehicle accident. For patients born with these conditions, symptoms usually become more noticeable when they reach their twenties. Diagnosis can be complicated since the source of the problem – causing pain or difficulty walking, sitting, or standing – may not be immediately apparent. Left untreated, however, these abnormalities may result in the development of labral tears, impingement and/or progressive hip joint arthritis.

It's important to note that in young children, some in-toeing or out-toeing is a normal gait pattern during skeletal development that will resolve on its own. However, such gait patterns that persist into adolescence may be a sign that the young person should be evaluated for alignment abnormalities of the hip and leg.

Diagnosing femoral abnormalities (version and shaft angle)

Many patients first seek medical attention because they are experiencing pain or restrictions in mobility. For any type of hip pain, orthopedists conduct a thorough patient history and physical exam. In many cases special imaging such as an MRI and/or CT scan will be ordered.

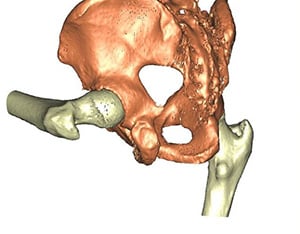

If we suspect that the patient has a femoral version abnormality or an abnormal femoral neck-shaft angle, we pay close attention to the degree of these angles, CT scans give us the best view of the bony anatomy and alignment, and current technology allows us to obtain these images with minimal radiation exposure to the patient. Should surgery become necessary, these images provide the surgeon with essential information that guides the correction of the angle. In addition, if the patient's condition is particularly complex, the orthopedic surgeon may ask for a 3D plastic model of the patient's hip to be created based on the scans, which also serves as a surgical guide.[Figures 4 and 5]

Figure 4A: Left: routine x-ray of the pelvis showing both hips;

4B: Right: a 3D model of the patient's hip created from CT scan images.

This image clearly shows the excessive anteversion and "uncoverage" of the femoral head.

Figure 5A: Left: One of multiple images obtained during CT scan showing bony anatomy and alignment;

5B: Right: a 3D model of the patient's hip created from CT scan images which demonstrates the

impingement that occurs during hip flexion.

Treatment

In some cases, patients with hip deformities are candidates for arthroscopic procedures, minimally invasive surgeries in which the surgeon uses a miniaturized camera and instruments to address issues such as loose or damaged tissue or to remove bone ridges causing impingement.

If the neck-shaft angle is too steep (coxa valga) or too flat (coxa vara), it can be corrected by applying a plate to the upper femur after cutting the bone. Often, the rotation (version) of the femur is abnormal as well and this is corrected at the same time. This procedure requires an incision long enough to apply the plate onto the femur. During the procedure, the orthopedic surgeon cuts the femur and corrects the angle and/or version of the bone. When the desired position is achieved, metal fixation (pins, plates or rods) is placed in the bone to stabilize the osteotomy site during bone healing.[Figure 6]

Figure 6: Varus Derotation Osteotomy

On the left; a hip with Coxa Valga, neck-shaft angle of 140°. Proposed surgery with a 90° blade plate.

On the right; after correction, the neck-shaft angle has been corrected to 127°, placing the femoral head deeper into the socket.

Although a femoral osteotomy can be significant surgery, it is possible to perform it in a minimally invasive manner. This means the surgeon is able to spare the muscles and other important structures that surround the hip." If the neck-shaft angle is normal, and the deformity is purely rotational (abnormal version), the operation is less invasive. Because a plate is not applied to the femur, the incision can be much smaller. The incision need be only long enough to insert a rod into the femur from above. The same incision is used to cut the femur from the inside without exposing the osteotomy (bone cut) site. In this manner, the muscles do not have to be elevated from the upper portion of the femur.[Figure 7]

Figure 7: The technique of femoral derotation osteotomy, for the left leg;

Figure 7A (left): The femur is prepared for an intramedullary nail and the intramedullary saw is inserted.

Figure 7B (right): Prior to performing the osteotomy, Steinmann pins are placed for rotational control in the desired amount of correction.

Figure 7: The technique of femoral derotation osteotomy, for the left leg;

Figure 7C (left): After performing the osteotomy, the femur is rotated to achieve the desired correction.

Figure 7D (right): The osteotomy is then stabilized with an intramedullary nail to maintain the correction while the bone heals.

Patients recovering from femoral osteotomy and hip surgery undergo careful monitoring during rehabilitation, with close supervision of joint motion, weight-bearing, muscle strengthening and progression of activity.

Outcomes at HSS

Patients may present with very complex conditions, involving multiple deformities, including those that affect the femur and hip joint as well as the tibia (the larger of the two bones in the lower leg). In such cases, HSS surgical specialists collaborate to perform procedures necessary to successfully treat all aspects of the patient's condition.

The excellent results achieved with femoral osteotomy and evolving procedures to correct femur and hip joint deformities and related conditions reflect the considerable progress made in understanding, diagnosing and treating these conditions. Nevertheless, early recognition remains very important, and hip pain in a young person should not be ignored. It's always advisable to seek care from hip specialists such as those who staff the HSS Center for Hip Preservation, where many of these surgeries are performed on a regular basis.

References

*Figure 2A,B,C Photo Credit: Illustration based off Jake Pett, B.F.A. and Stuart Pett, M.D illustration for International Association for Dance Medicine and Science 2011.