Spondylolysis and Spondylolisthesis in the Pediatric Patient

- Simple back pain or something more serious?

- Spondylolysis in youth athletes and active children

- Spondylolysis Causes, Symptoms and Diagnosis

- Nonsurgical treatments and recovery

- Orthopedic surgery for a child with spondylolysis

- Spondylolisthesis in children and teenagers

- Looking to the future

Simple back pain or something more serious?

Many young athletes pushing themselves to excel in sports like football or gymnastics may experience minor sports-related aches such as muscle or back pain. When persistent back pain interferes with participation in a favorite sport, however, it may be an indication of the presence of spondylolysis. Left untreated, spondylolysis can develop into spondylolisthesis and sideline an athlete for more than just a sporting season.

Today there are a number of highly effective nonsurgical treatments that are used to treat spondylolysis. And for those who are still experiencing pain after receiving nonsurgical care, effective surgical options are also available that help young athletes get back in the game.

Spondylolysis in youth athletes and active children

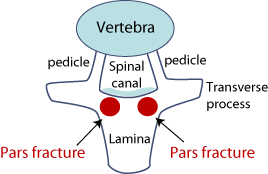

Spondylolysis is diagnosed when a stress fracture develops in the pars interarticularis (or "pars" for short) of the lumbar spine. This portion of the spine is vulnerable to injury from the repetitive flexion, extension and rotation common in many sports activities.

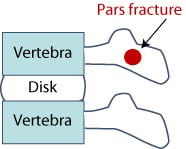

The injury to the pars, sometimes called a "pars defect" or "pars fracture") may occur at one or both sides of vertebrae in any section of the spine. It is most common, however, in vertebrae L4 and L5 – the lowest two segments of the lumbar portion of the spine.

Figure 1: Side view of spinal column

Figure 2: Top view of spinal column

Spondylolysis in children: Causes, symptoms and diagnosis

Traditionally, spondylolysis has been associated with gymnastics, rowing and football. But HSS is seeing greater numbers of patients with spondylolysis in almost every major sport, including skating, fencing, basketball, football, baseball and cheerleading. This is likely because childhood and adolescent athletics have become more competitive and intense over the years. Today, teenage athletes approach their sports more vigorously and often play multiple sports year-round. In addition to these young athletes, spondylolysis is also seen with greater-than-average frequency in young people who work on family farms and who regularly lift heavy loads.

Back pain is the main complaint, but symptoms of spondylolysis can include leg pain (which is commonly due to hamstring tightness) and muscle spasms. Patients or their parents sometimes mistake this pain to be sciatica, which has similar symptoms. The patient’s posture and gait (manner of walking) may also be affected.

A doctor's assessment begins with a physical examination and X-rays. At HSS, sophisticated imaging techniques that provide more detail are also often used to help confirm the diagnosis and to distinguish a pars fracture from a musculoskeletal stress reaction (such as tight or taught muscles), which can be a precursor to spondylolysis.

“We use both SPECT (single photon emission computed tomography) bone imaging and MRI that is formatted specifically for musculosketal imaging,” explains John S. Blanco, MD. "The latter is particularly important in yielding information about the pars and the posterior elements of the spine. MRIs obtained from facilities that do not specialize in musculoskeletal injuries are more likely to be formatted and aligned to look at the disk, and therefore may not provide all the information needed to make a proper diagnosis.”

Nonsurgical treatments and recovery

Most young athletes with spondylolysis can be treated with conservative management. This begins first with a period of rest – ceasing all vigorous sports and heavy weightlifting. In younger patients with acute symptoms of spondylolysis, a back brace is often recommended. Second, once the pain subsides, doctors usually have the patient begin a physical therapy program focused on increasing flexibility in the legs and gentle strengthening of the core muscle groups of the trunk. Third, the patient often prepares to return to sports activity with some more aggressive conditioning, such as running. In the fourth or final phase of treatment, the patient is allowed to return to sports.

However, the parents are asked to modify the child’s activities during his or her first season back in sports. “This can mean that the child participates in one sport season and plays on one team, instead of three or four different teams and year-round competition, as they may have done in the past,” says Roger F. Widmann, MD, chief of pediatric orthopedic surgery. Treatment and recovery may be as short as three months or take as long as a year, he notes. The long-term goal is a full return to sports without restriction.

Although the outlook is good, the diagnosis can come as a shock to young patients. "Most of these kids are very successful athletes whose daily routine for years has been based on a particular sport," says Dr. Blanco. "They’re very surprised to learn they have a stress fracture and that you’re recommending that they refrain from sports during recovery. To us it’s a relatively short period, but to a young person, three to six months can seem like a very long time, especially if they are anticipating participation in competition or other events."

Orthopedic surgery for a child with spondylolysis

A small minority of patients with a pars fracture (spondylolysis) may continue to experience pain after six months of bracing and rest. In these cases, surgery may be recommended.

Surgical treatment consists of either an arthrodesis (in which the affected vertebra is fused to the adjacent vertebra, thereby restricting motion) or direct repair of the pars fracture. This second approach preserves more motion in the spine. However, fusion has a higher healing rates and fewer incidents in which reoperation (additional surgery) is required.(Find a doctor or surgeon at HSS who treats spondylolysis.

Spondylolisthesis in children and teenagers

The primary concern with leaving spondylolysis untreated is that in some cases, the condition progresses to spondylolisthesis. This is where the vertebra with the pars fracture slips forward relative to the vertebra below it. In its mild form, this condition can also be treated conservatively. If the slippage exceeds 50% of the width of the vertebra, the patient may experience significant pain and be in danger of nerve injury.

Generally, surgical stabilization is recommended. This involves fusion and the use of surgical instrumentation to facilitate in healing.

“In the population of young athletes with spondylolysis, only about 5% will progress to spondylolisthesis,” notes Dr. Widmann. “But there are other causes of spondylolisthesis, particularly in adults; the condition may result from spine surgery which destabilizes the area, a tumor or severe arthritis, or it may be congenital in origin.”

Find a doctor or surgeon at HSS who treats spondylolisthesis.

Looking to the future

Treatment of children at risk for spondylolysis (and for spondylolisthesis that evolves from untreated spondylolysis) may benefit from ongoing research at HSS. Working together with scientists in the Department of Orthopedic Biomechanics HSS pediatric orthopedic surgeons are studying anatomic predisposition of the spine to spondylolysis in order to further understand the causes of the condition. They are also working with Richard Herzog, MD, Chief of the Division of Teleradiology, on a clinical imaging study of patients with stress reactions in the lower lumbar spine.

Find a doctor or surgeon at HSS who treats spondylolysis or treats spondylolisthesis.