Gait Analysis at HSS Motion Analysis Lab

Gait analysis is one of the many specialized tools available to help provide the best care for individuals with altered walking patterns. Sometimes it takes a computer and a team of engineers, physical therapists, and physicians to really know what the “eye” sees when a child walks.

What is gait analysis?

Gait analysis, also known as motion analysis, is a comprehensive, noninvasive 3D scan of the human body that both quantifies and qualifies the movements, muscle activity, forces, and energy used while walking. Although motion can be studied using two-dimensional videos, it is more accurate when instrumented technology is used. At HSS, the Leon Root, MD Motion Analysis Laboratory is the state-of-the-art.

How does gait analysis work?

Markers in the form of little reflective dots are affixed to specific parts of a person’s body. The motion laboratory then uses a sophisticated camera system, electromyography and force platforms (also called "force plates") to trace the movements of the legs, trunk, head and neck, the muscle activity, and measure the forces the person applies to the floor during walk. This type of movement analysis is called three-dimensional motion analysis or instrumented motion analysis.

A young girl undergoing gait analysis.

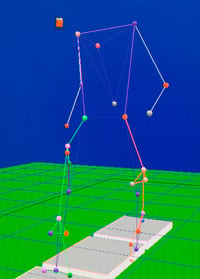

Computer image of the captured motion analysis data provides a visualization of a person's kinetics – how they move in three-dimensional space.

What is the reason for doing a gait analysis?

Gait analysis is used to study a wide variety of patients who have atypical gaits in order to help develop appropriate treatment plans. Motion analysis assists with in-depth understanding of the abnormal mechanisms the patient presents during gait.

Who can benefit from gait analysis?

People with abnormal gait patterns resulting from neuromuscular disorders such as cerebral palsy, spina bifida, head injuries, spinal cord injuries, and other conditions can benefit from gait analysis. Patients with malalignment of the leg bones (in which the femur and/or tibia bones are excessively turned either inward or outward) are also frequently referred to the motion lab for analysis.

The motion laboratory personnel and the referring physician or surgeon can then interpret and use the motion data to recommend nonsurgical or surgical treatments to improve patient’s gait.

Patients having surgery to improve their gait often receive a preoperative evaluation to determine their baseline and postoperative analysis to measure improvements afforded by surgery as well as to guide physical therapy regimens.

Can children have gait analysis?

Instrumented motion analysis becomes an essential assessment tool only once children can understand and follow commands. Clinicians start considering motion analysis for patients of around six years of age or older who have complex gait patterns, or when more invasive surgical treatments are being considered.

An HSS rehabilitation therapist placing equipment on a child in preparation for a motion analysis exam.

What are the different types of gait analysis?

Depending on the complexity of the gait pattern a patient presents, motion analysis can include two-dimensional video analysis only or video analysis in conjunction with the instrumentation that collects information of the movements (kinematics), internal forces the patients are using to walk (kinetics) and electromyography (muscle activity).

The motion lab can also measure foot pressure patterns during walking. The information is used to better understand foot deformity and its impact on gait as well as to treat such deformities.

What can I expect during a gait analysis appointment?

A motion analysis data capture may last up to three hours, depending on the complexities of the gait pattern being studied, the patient’s ability, and the modality of data being studied. Data is typically collected while individuals are walking barefoot, as well as while wearing any types of orthoses (braces) they typically use. This affords an opportunity to objectively compare these two situations. Data can also be collected while a person uses an assistive device such as rolling walker, crutches or a cane.

Patients should wear light clothes on the day of analysis. Patients should not expect any pain as a result of this exam. Patients should be rested and relaxed, and should not try to demonstrate their “best” walk but rather their most natural, everyday walking pattern.

Motion analysis laboratories are usually located in large rooms that have enough space for the patients to walk at self-selected speed on straight pathway.

How does gait analysis help determine the treatment approach for cerebral palsy patients?

By quantifying or measuring all the movements of the lower limbs, trunk, head and neck – as well as the forces and the muscle activity that produces the gait movements (both normal and abnormal) – motion analysis helps clinicians understand the pathological gait patterns more precisely and thoroughly in order to determine which specific treatments they recommend to a patient. Motion analysis has been around for more than 40 years. A significant amount of peer reviewed literature has been published in the last decade depicting all the information we have learned from this technology.

What can a gait analysis diagnose?

Motion analysis is not a tool for diagnosing diseases, but rather to identify and measure pathological gait patterns that resulting from various diseases of the central and peripheral nervous system as well as of joints, bones, and muscles. There have, however, been successful attempts of investigating specific pathological gait patterns and their relationship with certain disorders.

Gait analysis also helps clinicians determine primary and secondary gait pathologies. This means gait problems directly caused by a person’s condition versus those generated by methods they use to compensate for or cope with those problems. Determining these distinctions is important in deciding upon the optimal treatment.