Gout In Depth: Risk Factors, Diagnosis and Treatment

Gout can be extremely painful and incapacitating but is extremely treatable in almost all patients. It’s important to identify and treat it early to avoid pain and complications. Gout is a major problem in the foot, but it can also involve many other joints.

Overview of gout

Gout is an ancient disease associated with deposits of uric acid, especially in the joints and kidneys. The Egyptians identified local foot pain, notably in the big toe, as a specific disease in 2640 BCE, before the word “gout” was ever used. It was described by Hippocrates, who noted its high male-to-female ratio and its association with alcohol. Dr. Thomas Sydenham (1624-1689) described the lumps of uric acid (called tophi) that can be seen in gout, based on his own personal suffering. Until the early 19th century, however, gout was not well separated from other inflammatory types of arthritis. Only in the 20th century were the pathways of production of uric acid in the body truly understood and clarified, and it was proved that uric acid crystals have the ability to produce joint inflammation.

Gout can be extremely painful and incapacitating but is extremely treatable in almost all patients. It is most common in the big toe, and is also common in the midfoot, ankle, and knee. (See below for more details about how gout involves these and other joints.)

It’s important to identify and treat it early to avoid pain and complications. Women are not free of the risk of gout, and begin to “catch up” with men after they reach menopause.

Although alcohol can bring on gout attacks, genetics are much more important than alcohol in defining who gets gout, and many who never drink alcohol suffer from gout. In fact, it is believed that the French royal families who suffered from gout developed this condition more because of lead poisoning from the casks used for their wine than from the wine itself, since lead injures the kidneys and impairs their ability to remove uric acid from the system. This situation has been mimicked in more recent times when imbibers of “moonshine whiskey,” often made in radiators containing lead, developed a lead poisoning-associated gout (“Saturnine gout”). Excess body weight has also been associated with gout. The prosperous and overweight burgher with gout is a classical European image of the 19th century, but in reality gout affects those of all economic classes.

Gout is a common disease. It has been estimated that there may be as many as five million gout sufferers in the United States. Even more conservative estimates put this number at greater than two million (Mayo Clinic estimate). Population studies from both the Mayo Clinic and from Taiwan have shown significant increases in the prevalence of gout recently as compared to during the early 1990s.

The prevalence of gout has increased in both older and younger people. The increase in younger people may relate to excess weight and dietary issues. The increase in older people, at least in part, relates to increased life span, increased weight (obesity is associated with gout) and increased use of diuretics. Diuretics are used commonly for hypertension, for example, and they elevate the blood levels of uric acid and can increase the risk of gout.

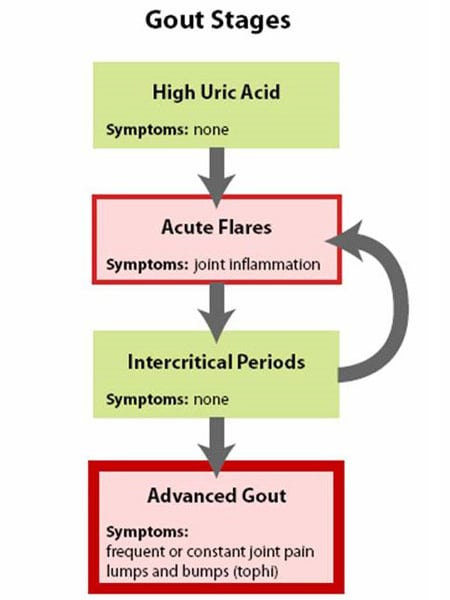

What are the four stages of gout?

Gout is best understood by seeing it as having four phases or stages (See Figure 1: Stages of Gout):

Stage 1: High uric acid

Elevated uric acid without gout or kidney stone, this stage has no symptoms and is generally not treated.

Stage 2: Acute flares

This stage is marked by acute gout attacks causing pain and inflammation in one or more joints.

Stage 3: Intercritical periods

These are periods of time between acute attacks, during which a person feels normal but is at risk for recurrence of acute attacks.

Stage 4: Advanced gout (chronic tophaceous gout)

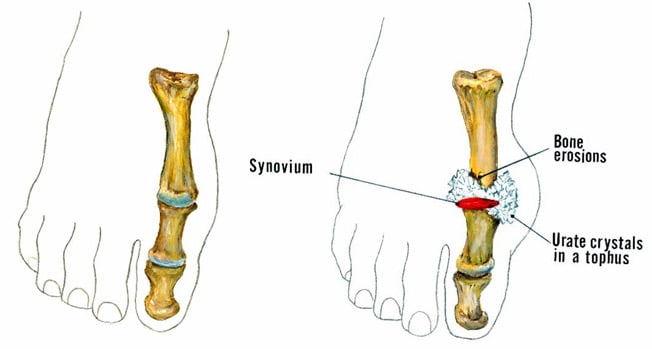

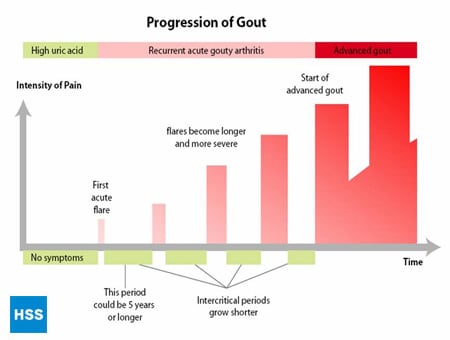

This is a stage of chronic gouty arthritis, in which there are “lumps” of uric acid, or “tophi” (see Figure 2: Illustration of Toe Joint With Gouty Tophus), frequent attacks of acute gout, and often a degree of pain even between attacks (see Figure 3: Progression of Gout).

A gout tophus can drain white uric acid crystals to the surface of the skin. Such gout tophus draining presents a risk of infection, since bacteria can track back through the skin and form a deep infection. In addition, patients with tophi are often at risk for uric acid-related kidney stones, since they may be over-producers of uric acid and have elevated 24-hour urinary uric acid.

Figure 1: Stages of Gout

Figure 2: Illustration of Toe Joint with Gouty Tophus. (Left) normal toe joint; (Right) Urate crystals, shown in white, at the "bunion joint," represent a gouty tophus.)

Figure 3: Progression of Gout

What causes gout?

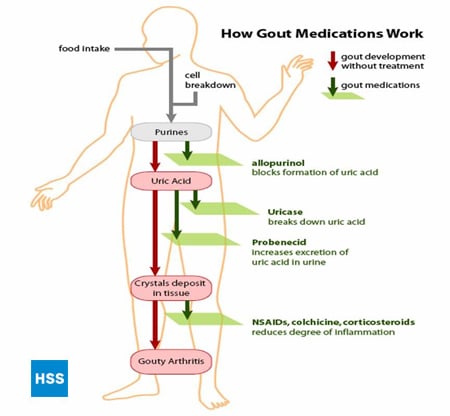

Gout is clearly associated with a buildup of uric acid. Uric acid is a produced as part of the body’s metabolism of purines, which are produced as the body breaks down any of the many purine-containing substances, including nucleic acids from our diet or from the breakdown of our own cells.

Figure 4, on the left side, shows a simplified pathway from purines to uric acid, and on the right shows how medications for gout work, which is discussed further in sections 5 and 6 below (Figure 4: Pathway from Purines to Uric Acid). Depending on the lab, normal values for uric acid run from 3.6 mg/dL to 8.3 mg/dL. Note that even though uric acid (urate) levels for 6-8.3 are considered “normal”, anything over 6 is bad for a gout patient – more on this later. The higher the blood level uric acid, the more the risk of deposits of uric acid in the joints and subsequent gouty attacks.

In mammals other than man and the great apes, the enzyme uricase breaks uric acid into the more soluble allantoin, which can be more easily excreted in the urine. Humans, lacking this enzyme, run higher levels of uric acid and are thus subject to gout.

Figure 4: Pathway from Purines to Uric Acid

Who gets gout?

Gout can develop in a person either because they are producing too much uric acid or because they are unable to put enough of it into the urine (or both). The most common cause of gout (about 90% of cases) is the inability to excrete enough uric acid in the urine. This inability may occur for a number of reasons. The most common is a genetic defect in substances referred to as organic anion transporters in the kidney, which leads to an excessive reabsorption of uric acid from the kidney – and thus too much uric acid in the blood. However, a defect in excretion of uric acid can also occur due to medications, such as diuretics, low dose aspirin, or alcohol. Defective uric acid excretion also occurs when the kidneys are functioning poorly.

About 10% of cases of gout are due to overproduction of uric acid. When uric acid is overproduced, it is high not only in the blood but in the urine, raising the risk of both gout and kidney stone. Some people overproduce uric acid due to a genetic defect in an enzyme in the purine breakdown pathway (See Figure 4) which leads to overactivity of this pathway. Since cells contain DNA, and DNA contains purines, anything that increases the breakdown of cells in the body can lead to more uric acid and gout. For example, if a patient is receiving chemotherapy for a tumor, as the treatment kills the tumor cells a gout attack or kidney stone can develop as a result of the breakdown of the purines from those cells.

Foods can also lead to overproduction of uric acid, such as meats and meat gravies and beer, which contain high levels of purines.

Men get gout more than women, and at younger ages; the male to female ratio is 9:1. The most common age of onset is from age 40 to 60 years. Gout is fairly rare in women until they reach menopause. One theory is that estrogen blocks the anion exchange transporter (see above) in the kidney, causing more uric acid to be excreted in the urine, and thus lowering the level of uric acid in the blood. Gout most commonly starts in a person’s 40’s to 60’s, although it can start earlier than the 40’s for those with a genetic predisposition, and it can also occur for the first time when someone is in their 80’s.

In some cases, injuries can set off an attack of gout. A “stub of the toe” can lead to a gout attack if there were already enough uric acid crystals saturating the cartilage.

Whatever the mechanism of the elevated uric acid, the key event in gout is the movement of uric acid crystals into the joint fluid. The body’s defense mechanisms, including the white blood cells (neutrophils) engulf the uric acid crystals, which leads to a release of inflammatory chemicals (called cytokines) which cause all the signs of inflammation, including heat, redness, and swelling and pain. This cycle also recruits more white blood cells to the joint, which accelerates the inflammatory process.

When thinking of gout, a useful model has been proposed by Wortmann.1 Uric acid crystals can be thought of like matches, which can sit quietly or can be ignited. Crystals can be present for years in the cartilage, or even in the joint fluid, without causing inflammation. Then, at some point, due to increasing number of crystals or other inciting factor, the matches are “struck” and the inflammation begins. This analogy is important both for conceptualizing the uric acid crystals in the joint and for understanding the various types of gout treatment (see below), some of which attack the inflammation (pour water on the flaming matches) and some of which remove the uric acid crystals (take away the matches).

Which joints are involved in gouty arthritis, and why is it most common in the foot?

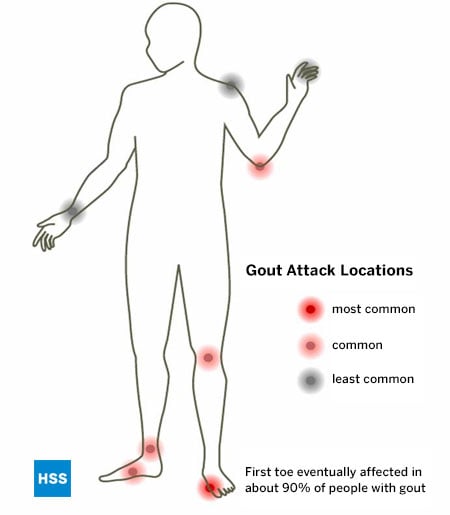

As with all other known types of arthritis, Gout has particular joints it tends to attack, and the foot is its most common location. Gout especially favors the bunion joint, known as the first metatarsophalangeal joint (at the base of the big toe), but the ankle, midfoot and knee are also common locations, as is the bursa that overlies the elbow.

The bunion joint is the first joint involved in 75% of patients and is ultimately involved in over 90% of those with this condition. (Figure 5: Location of Gout Attacks). It is thought that this joint is especially involved in gout because it is the joint that receives the highest pounds per square inch of pressure when walking or running.

Late in gout, if untreated, multiple joints can be involved, including the fingers and wrists. The shoulder joint is very rarely involved by gout and the same is true of the hip.

Figure 5: Location of Gout Attacks

What does a gout attack look and feel like? What would a foot or toe with gout look like?

When gout occurs, the joint tends to be extremely painful and is warm, red and swollen (Figure 6: Toe with Acute Attack of Gout). The inflammation that is part of a gout flare is systemic, so that fever and chills, fatigue and malaise are not uncommonly part of the picture of a gout flare.

Figure 6: Toe with Acute Flare of Gout

Gout flares can occur in joints that look normal, or in joints that have easily visible deposits of uric acid. These deposits are called tophi (See Figures: 7a and 7b: Tophi on Foot and Over Achilles' Tendon, Figure 8: Tophus on Elbow, Figure 9: Tophi on Hands, and Figure 10: Large Tophus of Finger) and can be in numerous locations, but especially on the feet and elbows. In Figure 9, the little finger of the right hand is bandaged since fluid was just removed from it, which demonstrated innumerable uric acid crystals.

Figure 7a: Tophi on Foot

Figure 7b: Tophus Over Achilles' Tendon

Figure 8: Tophus on Elbow

Figure 9: Tophi on Hands

Figure 10: Large Tophus of Finger

While some gout flares will solve quickly by themselves, the majority will go on for a week, several weeks, or even longer if not treated. Since gout flares are usually quite painful and often make walking difficult, most gout sufferers will request specific treatment for their painful condition.

How is gout diagnosed?

In a clear-cut case, a primary care physician can make the diagnosis of gout with a high level of confidence. However, often there are two or more possible causes for an inflamed toe or other joint, which mimics some of the symptoms of gout, so tests to identify the presence of uric acid is performed.

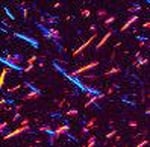

Since the treatment for gout is lifelong, it’s very important to make a definitive diagnosis. Ideally, the diagnosis is made by identifying uric acid crystals in joint fluid or in a mass of uric acid (tophus). These can be seen by putting a drop of fluid on a slide and examining it using a polarizing microscope, which takes advantage of the way uric acid crystals bend light. A non-rheumatologist, when possible, can remove fluid from the joint by aspirating it with a small needle and send it to a lab for analysis. A rheumatologist is more likely to have a polarizing attachment on their microscope at their office. Gout crystals have a needle-like shape, and are either yellow or blue, depending on how they are arranged on the slide (See Figure 11: Uric Acid Crystals Under Polarizing Light Microscopy).

Figure 11: Uric Acid Crystals Under Polarizing Light Microscopy

There are many circumstances where, however ideal it would be, no fluid or other specimen is available to examine, but a diagnosis of gout needs to be made. A set of criteria has been established to help make the diagnosis of gout in this setting (see Table 1- Diagnosis of Gout When No Crystal Identification Possible).2

These criteria take advantage of the features of gout that separate it from other types of inflammatory arthritis, such as rheumatoid arthritis. For example, the inflammation of gout tends to reach a maximum within 24 hours, while other types of arthritis tend to evolve more slowly. Likewise, the presence of redness over a joint, the involvement of the “bunion” joint, and a high blood level of uric acid are all features making gout more likely. The diagnosis of gout is made in the presence of 6 of the 10 criteria listed in Table 1.

Table 1: Diagnosing gout when no crystal identification is possible

Ideally, 6 of 10 features will be present of the following:

- Inflammation reaches a maximum within one day (rapid acceleration of inflammation).

- Having a history of similar episode of inflammation

- Attack of arthritis in a single joint.

- Redness over an involved joint (gout is highly inflammatory)

- Involvement of the base of the big toe on one side (the most common site for gout)

- Involvement of the joints at the middle of the foot

- Uric acid elevation on blood testing

- X-ray findings of swelling of joints which is not symmetrical

- Joint fluid is tested for infection and is negative.

- X-ray shows characteristic changes of gout, including cysts in bone and erosions.

When the diagnosis of gout is made, the individual must be evaluated for the complications of gout:

- Collections of uric acid (tophi) need to be searched for, and they can be in numerous locations (see Figures 7-10).

- Inquiry should be made regarding a history of kidney stone, since a patient with gout and kidney stones will likely require faster and more aggressive lowering of uric acid (see below) than one without stones, to try and prevent recurrent stone formation.

- A patient with gout has been shown in a broad range of studies to be at higher risk of coronary disease, and should have an evaluation appropriate to coronary risk (for example, lab testing for cholesterol and triglyceride level).3

It is important that damage to bone from gout be diagnosed, since documented damage is a clear indication for long-term therapy (see below). Once damage has begun, it’s important to reduce the total body uric acid level, which, by equilibration, causes uric acid to move out of the joints. This is because the blood and joint levels of uric acid reach a certain level, called a “steady state,” at a given level of blood uric acid. If the blood level is reduced, then the joint level of uric acid will gradually decrease as well. This leads to gout attacks diminishing or completely ceasing over time, and to tophi getting reabsorbed and shrinking or fully disappearing.

Different approaches can be taken to lowering total body uric acid. The production of uric acid can be decreased in the body (for example, by allopurinol, see below) or the excretion of uric acid can be increased (for example, by probenecid, see below). The crystals can also be broken down in the body (see 7a below, re: Rasburicase, and 7b below, re: pegylated uricase).

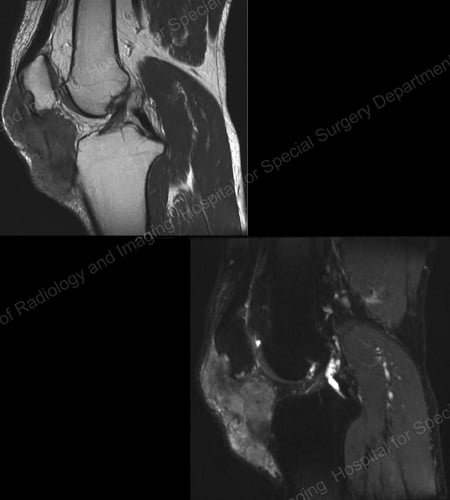

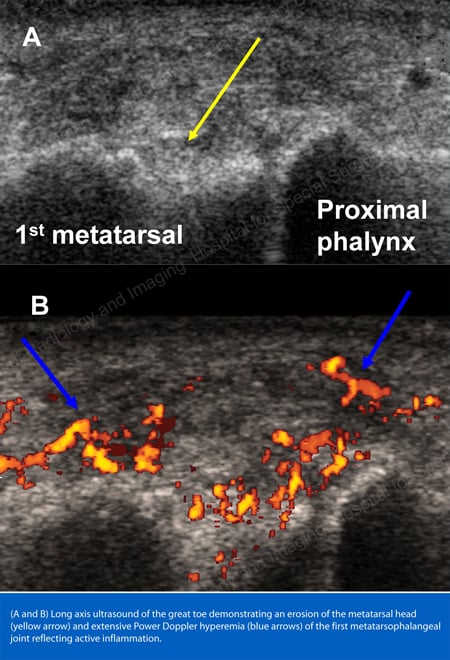

X-rays are the standard imaging technique for gout (See Figures 12-17: Figure 12: Gout of the Base of the 1st Toe; Figure 13: Gout of the Distal Finger Joints; Figure 14: Gouty Change and Soft Tissue Calcification About the Base of the 1st Toe; Figure 15: Gouty Destruction at Multiple Finger Joints; Figure 16: Gouty Erosion at the Proximal Ulna at the Elbow; Figure 17: Large Tophus Seen as Soft Tissue Mass at the Elbow) but in special cases, such as when gout needs to be separated from infection or tumor, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) (Figure 18: MRI of the Knee Showing Gouty Soft Tissue Mass and Erosion of the Kneecap) or ultrasound (Figure 19: Power Doppler Study Showing Gouty Inflammation at the Base of the 1st Toe) will be helpful. A newer technique called a dual-energy CT scan (DECT) can show urate crystals in green color.

Figure 12: Gout of the Base of the 1st Toe

Figure 13: Gout of the Distal Finger Joints

Figure 14: Gouty Change and Soft Tissue Calcification about the Base of the 1st Toe

Figure 15: Gouty Destruction at Multiple Finger Joints

Figure 16: Gouty Erosion at the Proximal Ulna at the Elbow

Figure 17: Large Tophus Seen as Soft Tissue Mass at the Elbow

Figure 18: MRI of the Knee Showing Gouty Soft Tissue Mass Erosion of the Kneecap

Figure 19: Power Doppler Study Showing Gouty Inflammation at the Base of the 1st Toe

The red and hot joints, coupled with rapid acceleration of joint pain, strongly suggest gout, and identifying tophi, if present (see Figures 7-10) help further.

Special effort should be made to distinguish gout from the other crystal-induced types of arthritis. For example, pseudogout, caused by a different type of crystal (calcium pyrophosphate), causes the same type of hot, red joint, and the same rapid acceleration of pain as does gout. Pseudogout can be distinguished by seeing calcium deposits within the joints on X-ray, which deposits in a different way than it does in gout. When fluid is examined from an inflamed joint in pseudogout, the specific causative crystal can be seen.

A third type of crystal-induced arthritis, hydroxyapatite deposition disease, has a type of crystal that needs special studies (one such study is electron microscopy) for identification. The presence of these other types of crystal-related inflammation further emphasizes the value of identifying uric acid crystals as the cause of a particular patient’s arthritis whenever possible, to insure that the correct condition is being treated.

Gout treatment: How can a gout flare be treated?

The management of an acute flare of gout is very different from the prevention of subsequent attacks. (See Figure 4 for overall approach to treatment and prevention of gout.)

Treatments used for prevention, such as allopurinol (see below) can actually make things worse if given during a flare, and so need to be held back until the flare has resolved for several weeks.

There are a number of measures that can help resolve an attack of gout. See Table 2 for summary of treatment strategies for acute gout. One principle is that treatment for an attack of gout should be instituted quickly, since quick treatment can often be rewarded with a quick improvement.

If an attack of gout is allowed to last more than a day or so before treatment is started, the response to treatment may be much slower.

Table 2: Medications to treat acute attacks of gout

- Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) or COX-2 inhibitors

Examples of NSAIDs: Naproxen 500mg twice daily, indomethacin 25mg three times daily. Example of COX-2 inhibitor: celecoxib 200mg twice a day. Possible side-effects: Elevation of blood pressure, ankle swelling, upset stomach, ulcer (long-term use may have an increased risk of heart attack or stroke, but gout use is generally very short-term). Use with caution if kidney or liver problems. - Anti-Inflammatory corticosteroids

Examples of anti-inflammatory corticosteroids: Prednisone 40mg first day, 30mg 2nd day, 20mg third day, 10mg fourth day. Possible side-effects: Elevation of blood pressure, elevation of blood sugar, mood changes. Short-term use, as in gout, generally much better tolerated than long-term use. Use with caution if diabetic. - Colchicine

In the past, high doses of colchicine were used for gout attacks, but this tended to cause diarrhea in a large number of patients. It has been shown that lower doses of colchicine are as effective as high doses for an attack of gout, and much better tolerated. Assuming no other medical problems that require an adjusted dose, for an attack of gout a patient would receive two tablets of colchicine, 0.6mg each, as soon as possible after a gout attack starts. They would then receive one additional tablet an hour later. Colchicine dose needs to be adjusted in patients with significantly decreased kidney function. Colchicine has interactions with certain other medications, most notably clarithromycin (Biaxin®). - Local steroid injections

Example of steroid injections: different doses used depending on the size of joint involved, and multiple preparations available. Possible side-effects: 1% to 2% of the time, a local reaction to the injection can occur, and the joint can temporarily worsen the next day, requiring ice application. In diabetics, a single local injection can temporarily raise blood sugar. - Should I walk with my gout?

Although exercise is great for helping lose weight and is generally fine for gout patients, when you have a gout flare in your toe, foot, ankle or knee it is advised to stay off the foot as much as possible until the flare resolves. Pounding on an inflamed gouty joint can prolong the flare. It’s fine to do other kinds of exercise, for example any exercise involving the upper body, but give the gouty joint a rest. This is another reason to treat gout flares quickly, since starting early often means the flare will be short – and you can limit your time off your feet.

Physical measures in treating an acute attack of gout

It is important to get off the foot if the gout attack is in the lower extremity. Trying to ignore the attack can lead to a more prolonged duration. Local ice has been shown to help (for not more than 10 minutes at a time, to avoid skin damage). Leg elevation is helpful for some.

Medications for acute gout

- Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory agents and COX-2 inhibitors are the mainstay of therapy of acute attacks of gout in patients who have no contra-indication to them. These medications include such agents as naproxen (Naprosyn®), ibuprofen (Motrin®), celecoxib (Celebrex®), indomethacin (Indocin®) and many others. These agents reliably decrease the inflammation and pain of gout. However, patients with ulcers, hypertension, coronary disease, and fluid retention must be careful with these agents, even for the short courses (usually 3 to 7 days) needed to resolve a gout attack. The doses of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory agents needed to resolve a gout attack are on the higher side, since full anti-inflammatory effect is needed. See examples of dosage in Table 2. Over-the-counter dosage levels, for example, ibuprofen at 200mg, two tabs three times a day, are often insufficient.

- Corticosteroids, such as prednisone and methylprednisolone (Medrol®), are anti-inflammatory agents that are quite effective against gout attacks. Anti-inflammatory steroids are very different in action and side-effects as compared to male hormone steroids. Anti-inflammatory steroids have long-term risks, such as bone thinning and infection, but their risk for short-term (for example, 3-7 days) therapy is relatively low. These agents can raise blood pressure and blood sugar, so can be a problem for those with uncontrolled hypertension or uncontrolled diabetes mellitus.

- Colchicine (Colcrys®, Mitigare®) has a role in both the prevention and treatment of gout attacks (see below for discussion of its role in prevention). See details about colchicine for attacks of gout in Table 2. An attractive feature of colchicine is how specific it is. For example, it can resolve an attack of gout, but it doesn't help a flare-up of rheumatoid arthritis. If the level of colchicine builds up too high, as it might if a usual dose is given to a patient with severe kidney disease, toxicity can occur, such as suppression of the production of blood cells. In the past, colchicine was also used intravenously in addition to its oral use. Intravenous use can be very effective, and doesn't cause diarrhea by this route, but this agent must be given extremely carefully, since an error in dosing can shut down the bone marrow’s production of blood cells, and potentially be fatal. For this reason, intravenous colchicine is very rarely used today. Patients often ask about why colchicine, which has been available in unbranded form for many years, is now a branded drug (Colcrys®, Mitigare®). This is a result of the FDA effort to review and standardize the production of drugs which have been around a long time and were not previously reviewed by FDA. Colchicine is one of a small number of drugs where new studies were done (for example, of drug interactions and re-evaluation of dosing) where the FDA has granted brand status to a manufacturer despite the unbranded form having long been available.

- Local injection of crystalline preparations of corticosteroid can be an excellent option if a person has a single joint gout attack. Formulations injected include methylprednisolone acetate (Depo-Medrol®), triamcinolone (Aristospan®), and betamethasone (Celestone®). Of these preparations, betamethasone lasts the shortest time in the joint of these preparations, but gout tends to be self-limited within a few weeks, in any case, so this option can be quite successful. The advantage of betamethasone is a decreased likelihood of temporarily worsened flares the day after the injection, which is the most common adverse reaction to local steroid injections. Local injections also carry a very small risk of introducing an infection into the joint but have the advantage that – if gout has not as yet been definitively diagnosed – a sample of fluid can be obtained using the same needle and analyzed for the presence of uric acid crystals.

- Anakinra (brand name Kineret®) is a biologic medication that blocks the inflammatory protein (cytokine) IL1. IL1 plays a major role in gouty inflammation. This medication is injected subcutaneously by the patient once a day, usually for 3 days, but can be used longer if needed to resolve a flare. Although much data supports the effectiveness and safety of this medication for gout, it is expensive and not as yet FDA approved for gout flares. It is still used off-label for gout, especially in hospitalized patients who often have risk factors that make the use of most other gout flare treatments more risky. In 2023, the FDA approved a longer-acting IL1 blocking medication called canakinumab (Ilaris) for use in special circumstances.

How can a gout attack be prevented?

Diet plays a key role in gout prevention: Since foods can directly set off gout attacks, patients with gout should receive counseling as to which foods are more likely to induce attacks. Losing weight is often also helpful. Despite the importance of diet and weight management, however, these alone are usually not enough to prevent gout attacks in most people, who will require medications to bring their uric acid levels down to the desirable amount.

The role of diet in gout prevention

Dietary control may be sufficient in a patient with mildly elevated uric acid, for example, 7.0 mg/dL (noting that any uric acid level above 6.0 is considered elevated for a patient with gout, even if within what the lab calls the “normal range.”)

For those with a higher level, for example, 10.0 mg/dL, diet alone will not usually prevent gout. For the latter, even a very strict diet only reduces the blood uric acid by about 1 mg/dL- not enough, in general, to keep uric acid from precipitating in the joints. The cut-off, where patients with gout seem to dramatically reduce their number of flares, is when their uric acid level is taken below 6.0 mg/dL.4

With the above qualifications, attention to diet in gout patients is helpful, and especially so when first starting medication to lower the uric acid (which may, paradoxically, initially set off gout attacks). There are a few basic principles of diet in gout which have stood up to a variety of studies: limit red meat and meat gravies, limit shellfish, and limit alcohol, especially beer.5,6 Red meat and shellfish (for example, scallops, shrimp, and mussels) should, ideally, be eaten less frequently, in smaller portions (for example, 3 oz or 85g). All types of alcohol cause more uric acid to be reabsorbed by the kidneys, raising blood uric acid levels, but beer has its own high purine level and so contributes to blood uric acid elevation in two different ways. Vegetable protein is broken down to purine, but does not seem to be a significant contributing factor in gout. Low fat dairy products, despite mild protein being broken down to purine, likewise seem not to contribute to gout risk (and may even be protective).5 Certain carbohydrates, such as oatmeal, wheat germ, and bran have moderate purine content but have not been shown to be significant gout risk factors. For those interested in achieving the maximal lowering of uric acid by dietary means, two “Gout Haters Cookbooks” are listed in the “Books about Gout” section below, and all four of their cookbooks can be purchased online.

The role of physical activity in prevention of gout

Along with diet, physical activity can help with weight loss, and gout has been associated with being overweight.7 in patients with well-established gout, especially if X-rays have demonstrated joint damage in the foot, a low-impact exercise program is reasonable. An exercise program combined with diet in gout can reduce risk for attacks.7 If an attack seems to be coming on in the lower extremity, patients are well-advised to try to get off their feet, since impact seems to worsen gout attacks. Clues to an attack of gout coming on include local swelling, heat, redness, and tenderness in a joint, especially in the foot, ankle, or knee. Some patients have fever and chills as the first warning that an attack of gout is coming on.

The role of medication in prevention of gout

(See Table 3 for summary of medications to prevent gout attacks.)

Table 3: Medications to pevent attacks of gout

- Colchicine: to decrease the ability of uric acid crystals to cause inflammation.

- Allopurinol and febuxostat: to decrease production of uric acid

- Probenecid: to increase the excretion of uric acid

- Pegloticase: to increase the breakdown of uric acid

Standard medications in preventing gout attacks

i. Colchicine (Colcrys®, Mitigare®): using the “matches” analogy discussed above1, using colchicine can be seen as “dampening” the uric acid “matches.” Colchicine does not lower the body’s store of uric acid, but it decreases the intensity of the body’s inflammatory reaction to these crystals. Recent studies have shown that at least one mechanism of colchicine’s action is by acting to prevent a cascade of reactions that lead to the production of interleukin 1-beta, which is an inflammatory protein (cytokine), which is important in gouty inflammation.8

When used as one or two tablets a day (0.6mg each), most people tolerate this medication well, and this dose can help prevent gout attacks. Some physicians would start colchicine after one very severe or two moderately severe attacks of gout, and beyond that, use allopurinol. If a patient has two attacks of gout within the same 12 months, it is generally recommended that they be treated with a medication to lower the uric acid, which colchicine does not accomplish. See below for discussion of the uric acid-lowering agents, allopurinol and probenecid. There is a rare effect on the nerves and muscles with long-term use of colchicine, and a blood test from the muscle (CPK) is monitored at approximately six-month intervals in patients taking colchicine on a regular basis. Colchicine also has a major role when patients begin therapy with allopurinol (see below) to prevent the increase in gout attacks that can happen when allopurinol is begun. The colchicine, in that case, is often withdrawn at about six months, assuming no gout attacks have occurred.

ii. Allopurinol: This agent is presently the most commonly used drug for the prevention of gout. Allopurinol blocks the enzyme xanthine oxidase, which blocks the breakdown of purines, thus decreasing the body’s total amount of uric acid. Allopurinol is effective in preventing gout no matter what the mechanism of the elevated uric acid was. Whether a person is making too much uric acid, or has difficulty excreting it via the kidney, allopurinol’s decrease in uric acid production leads to the same goal: a decreased total body uric acid.

Within a week after taking a dose, uric acid is significantly lowered by allopurinol. The most common adverse reaction to allopurinol is an increase in gout attacks early in therapy. For this reason it is initially often started together with colchicine (see above), so that while the “matches”1 are slowly removed, those remaining are “dampened.” Other adverse reactions to allopurinol include skin rash, abnormality of liver blood tests, and occasionally a drop in the white blood cell count. Ampicillin, an antibiotic, seems to cause more rashes in patients already taking allopurinol. A rare but very serious side-effect is the allopurinol hypersensitivity syndrome, which can present with severe rash along with severe liver and blood cell abnormality. This syndrome has been reported to be more likely if the patient has abnormal kidney function.9 Although there is some significant debate on this point10, it is generally agreed that patients with abnormal kidney function should start allopurinol at low doses and build up, to ensure that the allopurinol is effectively excreted. The level of uric acid in these patients is followed closely, and the level of uric acid is used as a guide as the allopurinol dose is slowly increased. The severity of the allopurinol hypersensitivity syndrome is a reminder that specific criteria must be used to decide which patients should be treated with allopurinol (See Table 4: Reasons to Use Medication to Lower Uric Acid).

Table 4: Reasons to use medication to lower uric acid

- Gout with more than two flares a year, whether due to overproduction of uric acid or difficulty excreting it

- Chronic visible collections of uric acid (tophi)

- High uric acid in the urine (over 800mg per 24 hours), especially if history of kidney stone

- Failure of other options to control the arthritis of gout (for example, failure of probenecid)

- When a person is receiving chemotherapy for a leukemia or a lymphoma and it is expected that many tumor cells will be killed (since one of the breakdown products of cells is purine which gets broken down to uric acid)

iii. Febuxostat (Uloric®): this medication was approved by the FDA in February 2009 for treating patients with gout by lowering their uric acid levels. It works similarly to allopurinol in that it inhibits xanthine oxidase, a key enzyme in the pathway that produces uric acid, and thereby reduces total body uric acid level.

Like allopurinol, the most common side-effect of febuxostat is causing gout to flare after this drug is started. As with allopurinol, it is reasonable whenever possible to add a preventative medication, such as colchicine, for at least the first six months after starting febuxostat to help avoid gout flares. Later on, as the total body uric acid decreases, this will generally no longer be needed.

One potential advantage of febuxostat is that it is structurally quite different from allopurinol, and therefore likely can be used in patients who are allergic to allopurinol. Only a limited number of patients who were allergic to allopurinol have been studied to date, but the drug was tolerated in those patients. Another advantage is that its excretion is handled more by the liver than the kidney, unlike allopurinol, and febuxostat may thus have some advantage in patients with kidney dysfunction.

Unlike allopurinol, which interacts with warfarin (Coumadin®), febuxostat did not have this interaction when studied. Febuxostat is approved by the FDA to start at 40mg daily, and if the uric acid has not reached goal (less than 6.0mg/dL) after two weeks of treatment the dose can be increased to 80mg daily. The 80mg dose of febuxostat brought more patients to less than 6mg/dL of uric acid than 300mg of allopurinol, the dose of allopurinol most commonly used. Rheumatologists often adjust allopurinol doses higher than 300mg when needed to reach uric acid goal, although the literature on higher doses of allopurinol is limited.

Patients with controlled uric acid level and doing well on allopurinol would seem to have no reason to switch to this new agent, in view of allopurinol's lower cost and 40-year history of an overall very good safety record (see "Allopurinol" discussion above).

In 2018, a study of allopurinol versus febuxostat heart safety was published. This study, the CARES trial, looked at 5000 patients, all of whom had some cardiovascular disease history, either heart attack, stroke, min-stroke or need for urgent heart surgery for coronary disease. The study looked at whether a combination of cardiovascular outcomes (heart attack, stroke, cardiac death, mini-stroke, urgent heart surgery for coronary disease) were more common in the allopurinol or the febuxostat group. For the combination of these outcomes, the two medications were the same. However, cardiac death was higher in the febuxostat group. There were some problems with interpreting the study, since almost all the patients who died had already stopped their gout medication, whether allopurinol or febuxostat. There was also a high drop-out rate in the 5 year study. Many rheumatologists do not think this is a definitive study, and there is other data that does not show increased heart risk with febuxostat. However, the FDA has interpreted this study and put a warning on febuxostat that it should be used second line, after allopurinol.

Now that the FDA has put this warning on febuxostat, even in people with kidney abnormality we would be likely to start allopurinol first. For people already on febuxostat who never took allopurinol, it is an individual case decision about whether to switch to allopurinol. It’s a hard decision, since they are tolerating febuxostat and may not tolerate allopurinol. Allopurinol has a higher risk of severe skin reaction in people with kidney function abnormality, and people with this abnormality are often the ones on febuxostat. After considering all this data, many patients in this situation have chosen to stay on febuxostat, but each person, with their physician, makes this decision.

However, in September 2020, The Lancet published the FAST trial, which is a European trial very similar to the CARES trial, found a different result. Here, there was no difference in death rates in patients on febuxostat compared to those on allopurinol. This trial actually had many fewer dropouts in the study and overall reviewers have felt that the FAST trial is a more solid base than the CARES trial on which to base decisions about the use of febuxostat. Some have called for the FDA to reconsider its recommendations, but no changes made to date. The FAST trial gives considerable comfort to those patients presently on febuxostat. It is generally agreed that we have no evidence that febuxostat is a negative for the heart, just the question of the CARES trial as to whether it is not as protective as allopurinol. The FAST trial challenges this, and it may well be that they are equally protective.

iv. Probenecid: This medication increases the amount of uric acid that is excreted in the urine, by decreasing the amount that gets reabsorbed by the kidney. Medications that can cause more uric acid to come out in the urine are called uricosuric agents. Probenecid is the main such agent used in the US. Probenecid can be successful in bringing the blood uric acid below 6.0 and reducing or preventing gout attacks.

Like allopurinol, an increased number of gout attacks can occur when probenecid is started, and for this reason colchicine is often given for the first six months of therapy. Unlike allopurinol, however, early in therapy probenecid can increase urinary uric acid, which could lead to the development of a kidney stone. For this reason, it is reasonable to check a 24-hour urine sample for uric acid before probenecid is started, and if this result is >800mg/24 hour, this therapy should be reconsidered. If the result is borderline, at a minimum the patient is advised to drink extra fluids, to help prevent kidney stones early on in treatment. There are also medications that can change the acidity of the urine, and by alkalinizing the urine in such a case the risk of kidney stone can be decreased (uric acid is more soluble in alkaline medium, so less likely to crystallize). Probenecid can also cause a rash but seems less likely than allopurinol to cause a very severe hypersensitivity reaction. Probenecid is not effective if a patient has kidney dysfunction [creatinine greater than 2.0 – (creatinine is a measure of a waste product excreted by the kidney). Because of the above limitations, allopurinol is often used as the drug of choice in a patient where lowering uric acid is the goal, but there remains a place for probenecid in the armamentarium (collection of medicinal resources) to manage gout.

v. Pegylated uricase – pegloticase (Krystexxa): This intravenous medication is extremely potent at markedly lowering the uric acid level quickly. It was approved in late 2010 for use in gout patients who have failed or were intolerant to both allopurinol and febuxostat. It appears that tophi shrink more quickly with this agent than with any other agent used to treat gout. An earlier Phase II trial11 and two essentially identical Phase III trials (a study of at least moderate size that compares a new treatment with the current standard of care in patients), Gout 1 and Gout 2 have been presented.13 Data on shrinkage of tophi with this agent was also presented in 6/09.13

Cardiac events have occurred during the studies of Krystexxa®, and the FDA reviewed them closely and concluded that they did not appear due to the medication. There were also allergic-type events and events where patients dropped their blood pressure while this intravenous agent was running into them. None of these episodes of drop in blood pressure led to death or long-term problems for the patients, however, and the blood pressure returned to baseline in these cases. The drop in blood pressure is still a concern, and this medication must be used in a setting where treatment of the drop in blood pressure can be managed. Pegloticase may be especially useful in patients with very large collections of uric acid (tophi), especially if these are draining to the skin.

Like Uloric®, Krystexxa® does not appear dependent on the kidney to be removed from the body, allowing it to be considered in patients with decreased kidney function. Because Krystexxa® is given intravenously, it would be expected that the great majority of its use would be by rheumatologists rather than by internists or primary care physicians.

More recent data has looked at ways to reduce the body forming antibodies to pegloticase. If we can prevent antibody formation, it has been shown that infusion reactions are dramatically decreased, and the effectiveness of pegloticase is also much better maintained. Early data has looked at medications such as methotrexate, mycophenolate mofetil (Cellcept) and azathioprine (Imura) given during the course of pegloticase treatment, and the results to date have been very encouraging. In 2022, the FDA officially approved the combination of methotrexate with pegloticase when pegloticase treatment is given.

What if a patient can't take the usual gout medications?

If a patient is allergic to allopurinol, there are often limited options. If the rash was relatively mild, one option is an oral desensitization regimen for that agent.11 This involves having a pharmacist put together a solution of allopurinol of very low and then gradually increasing concentrations over the course of a month. Although at times the rash will recur during this process, often a patient can be desensitized in this way and subsequently tolerate allopurinol. Although some patients develop a mild rash to allopurinol that remains mild over time, or respond to antihistamines, continuing the allopurinol despite a rash is not advised, since the rash can worsen unpredictably.

If a patient can’t tolerate allopurinol and meets the criteria (see above) for probenecid, that can be tried. There are some medications which are used for other indications but that have modest effect in lowering uric acid levels, such as losartan (Cozaar®), used for hypertension, and fenofibrate (Tricor®), used for elevated triglycerides, but these only infrequently can sufficiently lower uric acid level.

If none of the above options is possible or successful, physicians often seek a clinical trial of a new agent for gout, if available, for their patient to enter. See section 7 below for a discussion of agents presently under study for gout. Online resources, such as ClinicalTrials.gov, can help to identify clinical trials.

Alternative or complementary medications and supplements for gout

Gout is a common disease, and many medications and supplements have been tried.

Cherry juice, has been long an alternative remedy and with anecdotal support and has since been studied. At the American College of Rheumatology meeting in November 2010 (data available) there were two studies looking at cherry juice. It appears that cherry juice may have a small effect in decreasing production of uric acid. It also, possibly through its Vitamin C content, can increase the excretion of uric acid by the kidney.

In separate earlier study, Vitamin C itself did appear to increase uric acid excretion. However, the effect (using 500mg a day dosing) was small – only a drop in blood uric acid level of about 0.5 mg/dL, and almost all gout patients need to come down more than this to get to the goal of less than 6.0 mg/dL. These early studies of cherry juice are interesting, and might be relevant for a patient who was "almost there" in their uric acid goal, but a gout sufferer should be very careful about relying on cherry juice to manage their uric acid. Based on the data, the result is likely not going to be sufficient.

Diet has been discussed in more detail above, and gout is clearly one of the rheumatic diseases where diet is unequivocally important. Devil’s claw (Harpagophytum procumbens), curcumin (a component of turmeric) and many other herbal treatments have been proposed as gout therapy, and further study of these is indicated.

The main message of this review is to emphasize how dramatically effective standard medication is for gout, both in acute treatment and prevention. The safety profile of treatments for gout is generally quite good, despite the caveats mentioned above, for example, in the discussions of “colchicine” and “allopurinol.” For this reason, I believe that the great majority of gout sufferers would be well-served to explore traditional options for gout first and then choose their options. Many of my patients have explored a variety of non-traditional approaches to gout, often in combination with traditional measures.

My personal feeling is that herbal and other alternative/complementary approaches may well ultimately prove to improve inflammation in gout, but that lowering uric (with FDA-approved medications such as allopurinol) is the key to success in gout management.

Our present agents, such as allopurinol and probenecid, are so effective, and reasonably safe and predictable, that it seems unlikely that they will be fully displaced in the future. However, there are a small but very important group of patients who cannot tolerate these present agents. The development of new uric acid-lowering treatments, with even fewer side effects than our present agents, would be heartily welcomed.

When is surgery considered for gout?

The question of surgery for gout most commonly comes up when a patient has a large clump of urate crystals (a tophus), which is causing problems. This may be if the tophus is on the bottom of the foot, and the person has difficulty walking on it, or on the side of the foot making it hard to wear shoes. An especially difficult problem is when the urate crystals inside the tophus break out to the skin surface. This then can allow bacteria a point of entry, which can lead to infection, which could even track back to the bone. Whenever possible, however, we try to avoid surgery to remove tophi. The problem is that the crystals are often extensive, and track back to the bone, so there is not a good healing surface once the tophus is removed. In some rare cases, such as when a tophus is infected or when its location is causing major disability, surgical removal may be considered.

Since it is hard to heal the skin after a tophus is removed, a skin graft may be needed in some cases. For this reason, we often try hard to manage the tophus medically. If we give high doses of medication to lower the urate level, such as allopurinol, over time the tophus will gradually reabsorb. In severe cases, we may consider using the intravenous medication pegloticase (Krystexxa), since it lowers the urate level the most dramatically, and can lead to the fastest shrinkage of the tophus.

What are future possible treatments of gout?

Fortunately, present medications are successful in the vast majority of gout patients. But some patients cannot tolerate our present arsenal of gout medications. For others, these agents are not sufficiently effective. Therefore, new treatments are continually being sought. Some of the more promising include anakinra, rilonacept, canakinumab, BCX4208 and arhalofenate.

- Anakinra (Kineret): See discussion above. This biologic agent is presently approved by the FDA for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis, and we do use it “off label” in many cases of difficult-to-manage gouts. It works to block the receptor for interleukin 1-beta, an important inflammatory chemical (cytokine). Since interleukin 1-beta has been shown to be a key player in gouty inflammation (see under “colchicine for acute gout,” above), this agent has been studied in the treatment of gout attacks and appears to have been successful in preliminary study.14

- Rilonacept (Arcalyst): This is a fusion protein which acts as a blocker of interleukin 1- beta, and it has a longer duration of action than Anakinra. This agent has been studied in a 14-week trial and showed improvement in gouty symptoms.15 This agent may have a future role in preventing gout attacks when patients are started on a uric acid lowering agent but can take the usual prophylactic agents against the attacks that often are an early result of this therapy (for example, they can't use colchicine). There may also be selected patients where rilonacept treatment might be a longer-term alternative.

- Canakinumab (Ilaris): See above. This is FDA-approved in special situations with gout. It is a human monoclonal antibody which targets interleukin 1- beta, and a recent abstract looked at its ability to treat and prevent gout attacks, which showed some success.16 As with Rilonacept above, this agent may have a future role in the acute treatment and relatively short-term prevention of gout, and may have a longer-term role in selected patients with problems with multiple other options.

- BCX4208: This is a compound being studied as an alternative way to decrease the production of uric acid. It might be used alone, or together with a drug such as allopurinol or febuxostat in patients who otherwise could not have their uric acid level brought below 6. This agent works as a purine nucleoside phosphorylase inhibitor, a different mechanism than any of the medications to chronically lower uric acid described above. Early studies suggest that this new mechanism is effective in lowering uric acid levels.17

- Arhalofenate: This medication both lowers uric acid and decreases inflammation in gout, and is being studied as a medication that might allow urate to be lowered without adding a medication to decrease inflammation (such as colchicine).

- Medications that block the inflammasome: Several medications are under study which block the inflammasome, which is a group of proteins that work together to activate IL1, among other actions. As above, increased IL1 can stimulate gout flare, and blocking IL1 can quiet gout down.

- Medications that increase urate coming out in the urine: Several medications are under study which increase urate coming out in the urine, which can lower the uric acid in the body and lower gout risk. We already have probenecid (see above), but this medication has certain side effects and functional limitations that new medications may improve upon.

- Medications that block uric acid production: New agents are being looked at that block the production of urate (the way allopurinol and febuxostat do – see above). Newer agents may be more potent, or possibly have fewer side effects.

Summary

- Gout is a common disease and appears to be becoming more common over time. We are fortunate to have a strong armamentarium against this condition, with newer agents in development.

- In view of the effectiveness of our treatments, it is important for a correct diagnosis to be made as early as possible, and therapy begun quickly, when appropriate. Other conditions (for example, pseudogout) which can mimic gout, should be definitively ruled out through crystal identification in joint fluid whenever possible.

- Non-medication treatments for gout are important, such as staying off the foot when it is inflamed and attending to diet both to reduce purine intake and to lose weight when indicated.

- For acute flares of gout, it is key to treat as quickly as possible and choosing a medication least likely to cause side effects, with special attention to individual comorbidities. For chronic prevention of gout, the essential message is that present treatments work in a huge majority of patients and are generally well-tolerated.

- It is important for patients to understand the four stages of gout (See Figure 1) since the treatment of each is different. It is also important for patients with gout to be carefully counseled to communicate any changes in the frequency of gout attacks to their practitioner.

- A primary care practitioner can often manage gout without the patient having a consultation with a rheumatologist, but a consultation should be considered if the diagnosis is unclear, there is uncertainty as to whether or not to start uric acid-lowering medication, attacks continue to occur despite treatment, or possible medication side effects are making treatment difficult.

Disclosures

Dr. Fields serves on the Advisory Board of Horizon Pharmaceuticals and Avion Pharmaceuticals. He receives no compensation related to sales or prescription of any medications.

Additional web resources

- MedLine Plus – the NIH site for medical information for the public has valuable links on gout, including clinical trials, a Spanish version, interactive tutorial, nutritional information, and listing of organizations which can help patients with gout. This site is a valuable resource on the spectrum of arthritic disorders.

- Arthritis Foundation on Gout – a free printed copy of the pamphlet can also be ordered.

- Lab Tests Online – This site is a good resource to learn about uric acid blood test, what your lab test results mean, and why they are being done.

Gout Patient Stories

References

Books about gout (annotated bibliography)

- Schneiter J. Gout Hater's Cookbook: Recipes Lower in Purines and Lower in Fat. (Reachment Publications; 2000) In addition to comprehensive lists of foods lower, relatively high, and highest in purines, this book offers nearly 100 low-purine recipes.

- Schneiter J. Gout Hater's Cookbook II: The Low Purine Diet Cookbook. (Reachment Publications: 2001) More recipes from the same author. This book is useful since people often find the recommendations about low purine diets confusing and difficult to follow.

- Wortmann RL, Schumacher RH and Becker M: Crystal-induced arthropathies: Gout, pseudogout & apatite-associated syndromes. Lavoisier Booksellers, Cachan Cedex, France, 2006. A detailed review of the various types of crystal-induced arthritis, targeted at a professional audience.

- Emmerson B: Getting Rid of Gout: A Guide to Management and Prevention. Oxford University Press, London: 1996. A kidney specialist with special interest in gout explains the condition in detail for a lay audience.

- Parker JN and Parker PM (Editors): The 2002 Official Patient’s SourceBook on Gout. A Revised and Updated Directory for the Internet Age. Icon Health Publications, 2002. A source covering a wide variety of sources of information about gout, including a glossary and research summaries.

- Porter R and Rousseau GS: Gout: The Patrician Malady. Yale University Press, 2000. A socio-medical history of gout, including the famous figures who suffered from it, such as Benjamin Franklin and Thomas Jefferson.

- Wortmann RL. Effective management of gout: an analogy. Am J Med. 1998 Dec; 105(6):513-4. A review article that includes the "match" analogy to help patients understand the management of the various stages of gout, seeing uric acid as matches which can be “lit” (i.e. cause inflammation), “dampened” to decrease inflammation or removed from the joint.

- Modified from Wallace, SL, et al: Preliminary criteria for the classification of the acute arthritis of primary gout. Arthritis Rheum., 20:895, 1977.

- Baker et al: Serum uric acid and cardiovascular disease: Recent developments, and where do they leave us? Am J Med, 118:816-26, 2005. A review article concluding that uric acid is an independent risk factor for coronary disease.

- Shoji et al: A retrospective study of the relationship between serum urate level and recurrent attacks of gouty arthritis: evidence for reduction of recurrent gouty arthritis with antihyperuricemic therapy. Arthritis Rheum, 51(3):321-5, 2004. This is one among a group of studies demonstrating the benefit of keeping uric acid below 6.0 in gout patients.

- Choi HK et al: Purine-rich foods, dairy and protein intake, and the risk of gout in men. New Engl J Med, (11):1093-103, 2004. This article emphasizes the finding that red meat and shellfish increase gout risk while low-fat dairy intake seems to decrease it.

- Choi HK et al: Alcohol intake and risk of incident gout in men: a prospective study. Lancet, 363(9417):1277-81, 2004. This article pinpoints beer as being a particular risk factor for gout.

- Saag KG and Choi H: Epidemiology, risk factors, and lifestyle modifications for gout. Arthritis Res Ther 8 Suppl 1:S2, 2006. This article reviews lifestyle modifications that can influence gout risk, including weight loss, alcohol and diet.

- Drenth J and van der Meer J: The Inflammasome — A Linebacker of Innate Defense. N Engl J Med 355:730-732, 2006. A review of a recently recognized pathway by which colchicine inhibits the inflammatory process of gout.

- Singer JZ, Wallace SL: The allopurinol hypersensitivity syndrome: Unnecessary morbidity and mortality. Arthritis Rheum 29:82-6, 1986. This article stresses the importance of kidney abnormality as a risk factor in allopurinol hypersensitivity, and the importance of reducing allopurinol dose in patients with kidney dysfunction and of making sure that only patients who meet appropriate criteria get treated with allopurinol.

- Dalbeth N and Stamp L. Allopurinol Dosing in Renal Impairment: Walking the Tightrope Between Adequate Urate Lowering and Adverse Events. Seminars in Dialysis 20:5, 391-395, 2007. This review emphasizes that it has not been proven that severe allopurinol allergic reactions relate to dose or that they are more common in patients with kidney problems. The authors also stress that keeping doses of allopurinol too low often leads to inadequate control of uric acid levels.

- Sundy JS et al: Reduction of Plasma Urate Levels Following Treatment With Multiple Doses of Pegloticase (Polyethylene Glycol–Conjugated Uricase) in Patients With Treatment-Failure Gout: Results of a Phase II Randomized Study. Arthritis Rheum 58:9, 2882-2891, 2008.

- Sundy JS et al: Efficacy and Safety of Intravenous Pegloticase (PGL) in treatment failure gout (TFG): Results from Gout-1 and Gout-2. European League Against Rheumatism Abstract THU0446, June 2009. Abstract from European League Against Rheumatism Meeting 2009

- Baraf, HSB et al: Reduction of tophus size with pegloticase (PGL) in treatment failure gout (TFG): Results from Gout-1 and Gout-2, European League Against Rheumatism Abstract OP-0047, June 2009. Abstract from European League Against Rheumatism Meeting 2009

- So A et al: A pilot study of IL-1 inhibition by anakinra in acute gout. Arthritis Research & Therapy 9(2):R28, 2007. Early data that anakinra was effective in gout flares.

- Terkeltaub R et al: The interleukin 1 inhibitor rilonacept in treatment of chronic gouty arthritis: results of a placebo-controlled, monosequence crossover, non-randomised, single-blind pilot study. Annals of Rheumatic Disease 68:1613-1617, 2009

- So A at al: Canakinumab (ACZ885) Vs. Triamcinolone Acetonide for Treatment of Acute Flares and Prevention of Recurrent Flares in Gouty Arthritis Patients Refractory to or Contraindicated to NSAIDs and/or Colchicine. American College of Rheumatology Abstract LB4, October 2009. Abstract from American College of Rheumatology Meeting, Oct. 2009.

- Fitz-patrick D et al: Abstract 150: Effects of a Purine Nucleoside Phosphorylase Inhibitor, BCX4208, on the Serum Uric Acid Concentrations in Patients with Gout. Abstract from the American College of Rheumatology Meeting November 2010.