Progressive Dyspnea and Cough in a Healthy, Young Man

From Grand Rounds from HSS: Management of Complex Cases | Volume 8, Issue 3

Case Report

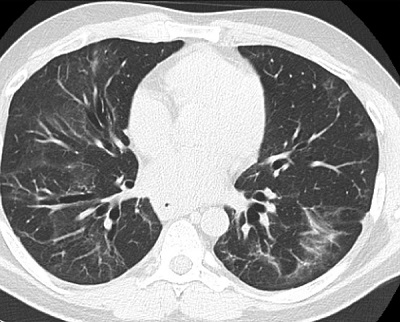

A 36-year-old previously healthy man presented with progressive shortness of breath and dry cough for 3 months and intermittent fevers for 2 weeks. He had no Raynaud’s phenomenon, joint pain, muscle weakness, or skin changes. A chest radiograph demonstrated bilateral basilar infiltrates. Computed tomography (CT) angiography showed bilateral basilar ground-glass opacities, traction bronchiectasis, and a dilated thickened esophagus without pulmonary embolism. He was treated with antibiotics without improvement. A bronchoscopy with biopsy was performed, and pathology from the small sample was read initially as organizing pneumonia. Prednisone 60 mg daily was started. His cough and fevers resolved; however, he subsequently experienced worsening dyspnea, 15-lb. weight loss, dysphagia, and proximal muscle weakness. On the 6-minute-walk-test (6MWT), he desaturated to 90%, with a Borg dyspnea score of 4 (“somewhat severe”). Repeat CT demonstrated worsening ground-glass opacification (Fig. 1).

Figure 1A: Initial CT scan of the lungs demonstrates bilateral ground-glass opacities and peribronchovascular consolidation.

Figure 1B: Follow-up CT scan, 8 months later, demonstrates significant improvement in the areas of ground-glass and consolidation with persistent mid- to lower-lobe traction bronchiectasis consistent with fibrotic non-specific interstitial pneumonia without progression.

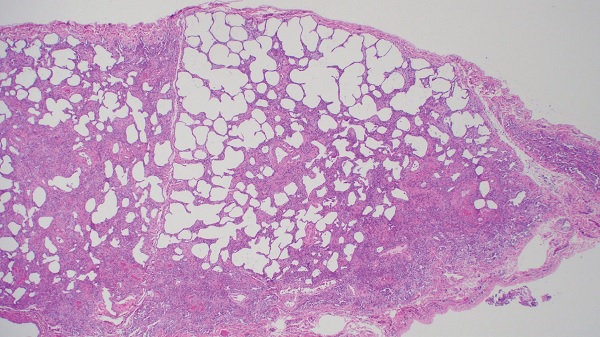

The patient was readmitted for pulmonary disease progression despite high-dose steroids. Bacterial cultures and tests for respiratory viruses, aspergillus, Pneumocystis jiroveci pneumonia, HIV, and tuberculosis were negative. Antinuclear antibody titer was 1:80 (speckled). Other serologic tests were negative including rheumatoid factor and autoantibodies against cyclic citrullinated peptide, Ro (SSA), La (SSB), double-stranded DNA, ribonucleoprotein (RNP), myeloperoxidase, proteinase-3, Jo-1, Scl-70, anticentromere, RNA polymerase III, and anti–glomerular basement membrane. With steroid therapy, creatine phosphokinase level was normal, and aldolase level was mildly elevated (9.2 U/L; upper limit: 8.1). The patient had an isolated urinalysis with hematuria that resolved on repeat study. On re-evaluation of the small initial biopsy sample, there was concern for capillaritis. Repeat lung biopsy was pursued given diagnostic uncertainty and showed mixed cellular and early fibrotic non-specific interstitial pneumonia (NSIP) (Fig. 2). Cyclophosphamide was given by IV, and eventually a myositis-specific serologic panel was positive for anti-PL-12 (alanyl-tRNA synthetase) antibody.

Figure 2: Right lower lobe lung biopsy demonstrates mixed cellular and early fibrotic non-specific interstitial pneumonia (image courtesy of Alain Borczuk, MD).

The patient was diagnosed with antisynthetase syndrome and received monthly IV cyclophosphamide for 6 months, with an excellent response, evidenced by clinically significant improvement in 6MWT distance (92 m) and Borg dyspnea score (2-unit improvement). Steroids were tapered, and mycophenolate was initiated for maintenance. Eight-month CT imaging improved significantly (Fig. 1). After 12 months of treatment, forced vital capacity was 94% predicted (from 89% 3 months post-treatment), and diffusing capacity for carbon monoxide was 62% predicted (from 57% 3 months post-treatment). Eighteen months after diagnosis, the patient had no pulmonary, musculoskeletal, or gastrointestinal symptoms.

Discussion

Clinical features of antisynthetase syndrome include myositis, interstitial lung disease (ILD), arthritis, fever, and Raynaud’s phenomenon [1]. The most common radiographic ILD patterns are NSIP and organizing pneumonia [1]. Autoantibodies in antisynthetase syndrome include anti-Jo-1 (most common), anti-PL-7, anti-PL-12, anti-EJ, anti-OJ, anti-KS, anti-Zo, anti-SC, anti-JS, and anti-YRS [1]. Differences in disease features by antisynthetase antibody have been observed. Specifically, anti-PL-12 positivity is associated with amyopathic dermatomyositis and isolated ILD [2], and patients with anti-PL-12 antibody (vs. anti-Jo-1 antibody) have more severe ILD and worse prognosis [1]. Accordingly, among 202 patients with antisynthetase syndrome, 5-year survival was better in patients with than those without anti-Jo-1 antibody (90% vs. 75%, respectively; p < 0.005) [3].

Randomized controlled trials testing therapies in antisynthetase syndrome are lacking. Steroids are considered first-line treatment; however, steroid monotherapy is associated with frequent disease flares. Other immunosuppressive agents used off-label include azathioprine, mycophenolate, tacrolimus, rituximab, and cyclophosphamide [1]. In a systematic review, data was pooled from 12 nonrandomized studies that included 141 patients with idiopathic inflammatory myopathy–associated ILD treated with cyclophosphamide [4]. Cyclophosphamide was associated with forced vital capacity and diffusing capacity for carbon monoxide improvement in 58% and 64% of patients, respectively [4]. Our case illustrates symptomatic and radiographic improvement of antisynthetase syndrome treated with cyclophosphamide with durable response at 18 months on mycophenolate maintenance therapy.

Posted: 10/1/2019

Authors

Attending Physician, Hospital for Special Surgery

Assistant Professor of Medicine, Weill Cornell Medical College

Xiaoping Wu, MD, MS

Assistant Attending Physician New York-Presbyterian Hospital

Instructor of Medicine Weill Cornell Medicine

Attending Physician, Hospital for Special Surgery

Associate Professor of Medicine, Weill Cornell Medical College

References

- Witt LJ, Curran JJ, Strek ME. The diagnosis and treatment of antisynthetase syndrome. Clin Pulm Med. 2016;23(5):218–226.

- Hamaguchi Y, Fujimoto M, Matsushita T, et al. Common and distinct clinical features in adult patients with anti-aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase antibodies: heterogeneity within the syndrome. PloS One. 2013;8(4):e60442.

- Aggarwal R, Cassidy E, Fertig N, et al. Patients with non-Jo-1 anti-tRNA-synthetase autoantibodies have worse survival than Jo-1 positive patients. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73(1):227–232.

- Ge Y, Peng Q, Zhang S, Zhou H, Lu X, Wang G. Cyclophosphamide treatment for idiopathic inflammatory myopathies and related interstitial lung disease: a systematic review. Clin Rheumatol. 2015;34(1):99–105.