Polyuria in a 31-Year-Old Man with Uveitis, Rash, and Periarthritis: An Application of Occam’s Razor

From Grand Rounds from HSS: Management of Complex Cases | Volume 12, Issue 3

Case Report

A 31-year-old man presented to the emergency department with 4 weeks of ankle pain and swelling. He had been healthy until 5 months earlier when he developed bilateral blurred vision and photophobia, followed by right-sided facial droop and lower extremity paresthesia. He also experienced low-grade fevers, 17-lb unintentional weight loss, dyspnea, and fatigue. His only medications were atropine and prednisolone eye drops, prescribed by an optometrist for his ocular symptoms. He had immigrated to the U.S. as a child and had no recent travel. He recently stopped drinking heavily due to his symptoms but otherwise used no substances and had no unusual environmental exposures or family history of autoimmune disease.

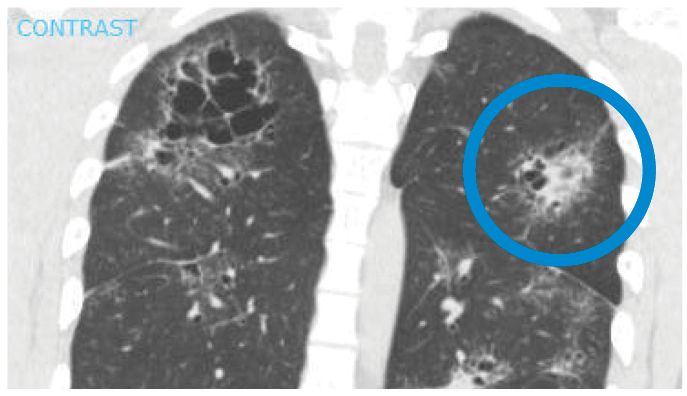

On initial evaluation, his pulse was 126 beats/min and temperature was 38.6°C. He had right facial palsy, bilateral ankle periarthritis, active bilateral anterior uveitis, and sequelae of prior panuveitis. Initial laboratory studies were notable for maximally dilute urine. Chest X-ray and computed tomography (CT) scanning showed interstitial infiltrates, bilateral hilar lymphadenopathy, multifocal peribronchovascular bronchiectasis, and “galaxy signs" (Fig. 1). Ankle radiographs were unremarkable.

Figure 1: CT scan of the chest showing galaxy sign in sarcoidosis: an irregular lesion formed by dense, central coalescence of granulomas associated with diffuse granulomas in the periphery, radiographically resembling a galaxy.

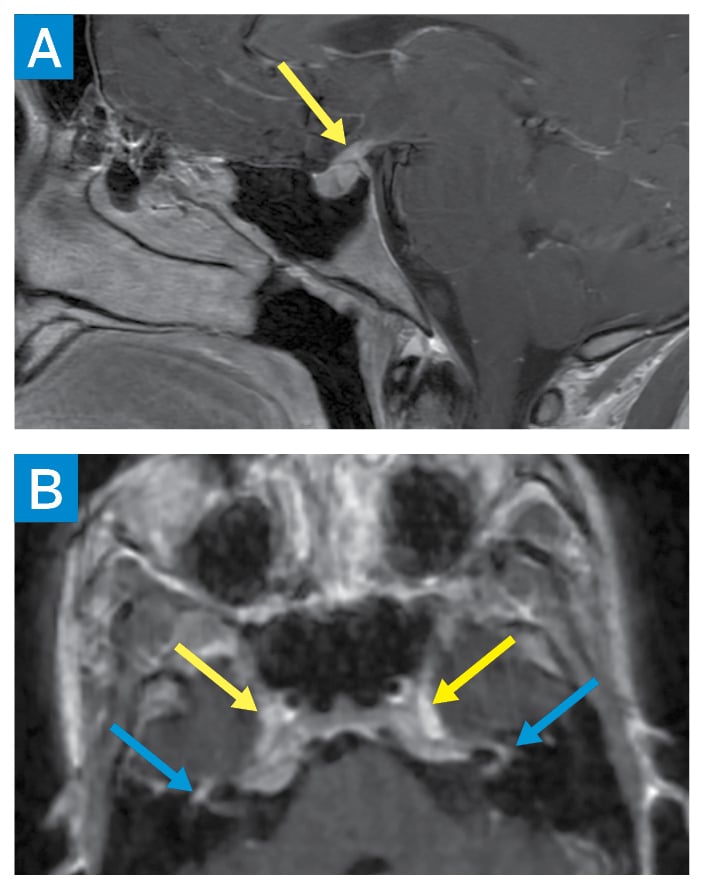

Subsequent studies revealed elevated serum angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE), lysozyme, and interleukin-2 receptor levels, as well as low vitamin D-25OH, normal vitamin D-1,25OH, and a negative QuantiFERON-TB Gold assay. Bronchoscopic transbronchial lung biopsy showed non-necrotizing granulomas with negative acid-fast bacilli and fungal staining. Electrocardiography, continuous telemetry, and cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) were unrevealing. Brain MRI demonstrated thickening of the infundibulum and enhancement of bilateral facial nerves and Meckel’s caves (Fig. 2). Cerebrospinal fluid showed elevated protein and ACE levels.

Figure 2: Brain MRI showing sagittal postcontrast T1 image of the sella turcica with abnormal thickening of the pituitary infundibulum (yellow arrow) (A). Axial 3D T1 postcontrast facial nerves partially visualized within the internal auditory canals, labyrinthine segments, and geniculate ganglia (blue arrows) (B). Abnormal enhancement is also seen along the bilateral trigeminal nerve ganglia within the bilateral Meckel’s caves (yellow arrows).

While hospitalized, the patient was incidentally found to have polyuria, with urine output up to 8L/day; he retrospectively reported polydipsia. Water deprivation testing was consistent with central diabetes insipidus (DI). Sarcoidosis with pulmonary, ocular, musculoskeletal, and neurologic involvement was diagnosed. Prednisone 60 mg daily, methotrexate 7.5 mg weekly, and intranasal desmopressin 0.1 mg nightly were initiated, with global symptom improvement.

Six months after hospital discharge, the patient presented to rheumatology and ophthalmology clinics, having discontinued his medications. He had recurrence of panuveitis and new nodules in multiple tattoos, consistent with tattoo sarcoidosis (Fig. 3). Prednisone 40 mg daily and methotrexate, increased to 20 mg weekly, were resumed, with consideration for infliximab. Dermatology, neurology, endocrinology, and pulmonology referrals were made. At last follow-up, the tattoo sarcoidosis had improved, with repeat imaging and pulmonary function testing pending.

Figure 3: Suspected granulomatous nodule formation in tattoos (yellow arrows).

Discussion

Sarcoidosis is an idiopathic multisystem granulomatous disease with heterogenous presentation. This case is notable for the extent and severity of organ involvement, as well as multiple highly specific features for which the differential diagnosis is narrow: bilateral non-infectious panuveitis, bilateral hilar lymphadenopathy, galaxy sign, multifocal neuroaxial involvement, and tattoo sarcoidosis. Tattoo pigment is generally not thought to induce sarcoidosis, but rather provides a local target of systemic inflammation [1]. While elevated serum ACE, lysozyme, vitamin D-1,25OH and interleukin-2 receptor levels occur, there is no single biomarker for the disease. Diagnosis is made clinicopathologically, with exclusion of other diagnoses and demonstration of well-formed, non-necrotizing granuloma on histology. Biopsy is diagnostically unnecessary in some specific phenotypes such as Lofgren’s syndrome (bilateral hilar lymphadenopathy, erythema nodosum, periarthritis), lupus pernio, and Heerfordt syndrome (uveitis, facial nerve palsy, parotitis) [2].

Treatment of sarcoidosis is directed at organ-specific manifestations, with systemic immunosuppressive therapies required in roughly 25% of patients [3]. Neuroendocrine involvement is rare; up to 5% of patients with neurosarcoidosis have hypophysitis [4, 5]. Limited experience with central DI due to sarcoidosis suggests the need for chronic immunosuppression and lifelong desmopressin therapy [5]. Currently, systemic corticosteroids are the only approved treatment for sarcoidosis, although nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, local corticosteroids, systemic immunomodulators, and antifibrotics are all used as part of multimodal treatment.

References

- Ruffer N, Haberstock H, Bohne AS, Kötter I, Mrowietz U. Papulonodular tattoo lesions as a clinical sign of systemic sarcoidosis. Clin Rheumatol. 2022;41(8):2589-2590.

- Crouser ED, Maier LA, Wilson KC, et al. Diagnosis and detection of sarcoidosis. An official American Thoracic Society clinical practice guideline. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;201(8):e26-e51.

- Baughman RP, Field S, Costabel U, et al. Sarcoidosis in America. Analysis based on health care use. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2016;13(8):1244-1252.

- de Waard WIQ, van Battum PLH, Mostard RLM. Central diabetes insipidus due to sarcoidosis. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis. 2017;34(2): 191-193.

- Tabuena RP, Nagai S, Handa T, et al. Diabetes insipidus from neurosarcoidosis: long-term follow-up for more than eight years. Intern Med. 2004;43(10):960-966.