Intravascular Lymphoma of the Brain Masquerading as Neurosarcoidosis in a 63-Year-Old Man

From Grand Rounds from HSS: Management of Complex Cases | Volume 11, Issue 3

Case Report

A previously healthy 63-year-old man presented with headache, gait instability, and short-term memory loss, 8 months prior to admission (PTA). Diagnostic workup revealed mild anemia and a high serum angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) level. He tested negative for syphilis, Lyme, HIV, lupus, and antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA). Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain revealed abnormal leptomeningeal enhancement (LME) and small subacute infarctions. A positron emission tomography (PET)–computed tomography (CT) scan showed mild splenomegaly and a lung nodule with poorly formed granulomas on biopsy. Cerebrospinal fluid testing showed mild lymphocytosis and elevated protein and was negative for pathogens. Symptoms gradually improved without treatment. Serial outpatient brain MRIs showed waxing and waning LME and patchy T2 white matter hyperintensities with mild diffusion restriction. Autoimmune encephalitis antibody panel was negative.

One month PTA, because of the inconsistent brain lesions, treatment for presumed neurosarcoidosis was started. Brain biopsy was deferred, given interval improvement in lesions and anticipated low yield of a non-targeted biopsy. After a short illness with COVID-19, 20 days PTA the patient began prednisone 40 mg daily and azathioprine. Six days PTA, he developed sore throat, headache, and high fever. Prednisone was tapered to 5 mg daily, and azathioprine was discontinued.

The patient presented to the emergency department with dyspnea, mild confusion, and aphasia. He had high serum inflammatory markers, new moderate thrombocytopenia, low albumin, and high lactate dehydrogenase and ACE levels. Nasopharyngeal swab was negative for SARS-CoV-2, and there was no pulmonary embolism. Brain MRI showed numerous bilateral foci of restricted diffusion, concerning for acute ischemia. MR angiogram was unremarkable.

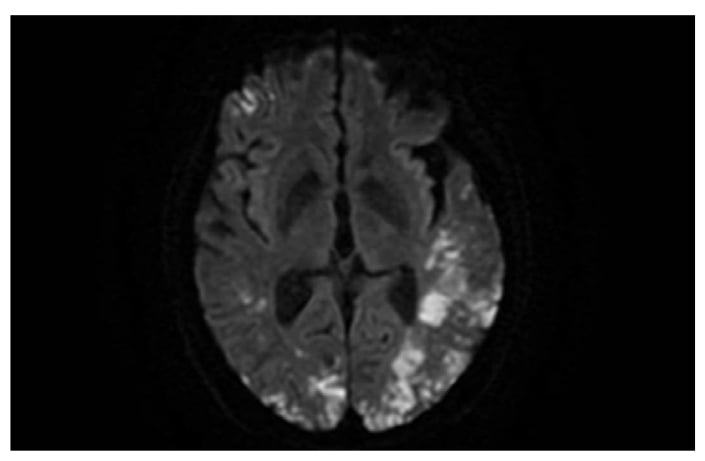

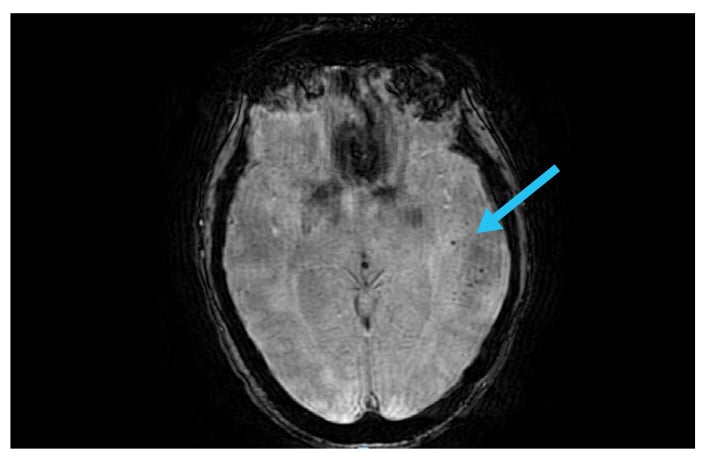

He was empirically treated with pulse glucocorticoids but did not improve. MRI showed new extensive restricted diffusion areas with associated T2 hyperintensities and microhemorrhages (Fig. 1 and Fig. 2). Hematology workup for heparin-induced thrombocytopenia and thrombotic microangiopathy was negative. β2-microglobulin was elevated, but there was no M-protein. Skin, bone marrow, and transbronchial biopsies were unrevealing.

Figure 1: Diffusion-weighted MRI shows cytotoxic edema from infarction.

Figure 2: Susceptibility-weighted MRI; blue arrow indicates hemorrhages.

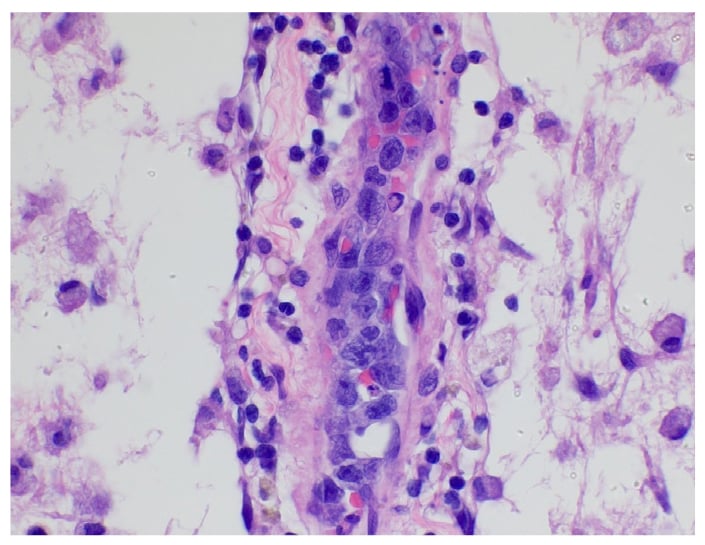

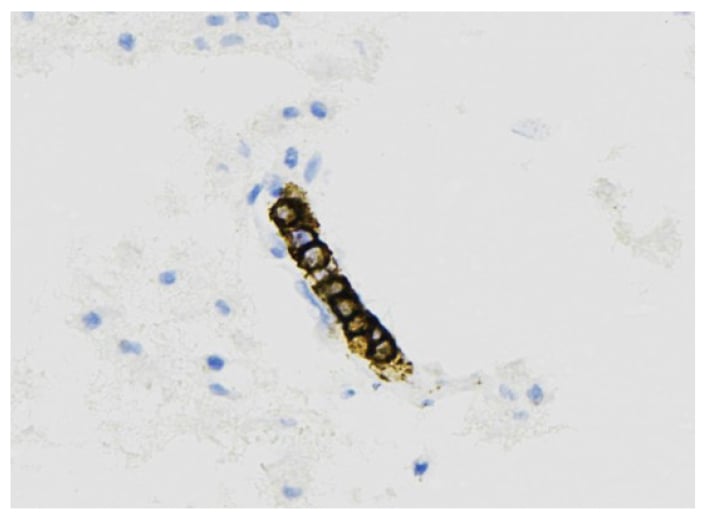

Brain biopsy was performed 3 weeks after admission, showing CD20+ atypical cells (Fig. 3) limited to the lumen of the small vessels (Fig. 4), consistent with intravascular lymphoma (IVL). He was started on systemic chemotherapy with rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone (R-CHOP) and transferred to another facility.

Figure 3: Blood vessel with atypical cells.

Figure 4: CD20+ neoplastic lymphoid cells.

Discussion

A rare form of lymphoma usually seen after age 50, IVL is characterized by malignant B cells restricted to the lumina of small vessels, particularly capillaries and postcapillary venules, causing microvascular ischemia of affected organs [1]. A “classical” variant of IVL features fever and cutaneous and central nervous system (CNS) involvement; a “hemophagocytic” variant features hemophagocytosis and cytopenia [2].

The most common CNS presentation is encephalopathy/dementia, as in our case [3]. When small-vessel ischemic changes on brain imaging are extensive or confluent, IVL should be suspected, along with neurosarcoidosis, acute disseminated encephalomyelitis, multiple sclerosis, and CNS lymphoma [4]. Lesional or non-lesional skin biopsies may be diagnostic, as may biopsies of other affected organs. If those biopsies are negative, brain biopsy is needed. IVL is often treated with R-CHOP and CNS-directed therapy such as intrathecal methotrexate. Prognosis is generally poor, but better for isolated cutaneous IVL [5].

References

- Tahsili-Fahadan P, Rashidi A, Cimino PJ, Bucelli RC, Keyrouz SG. Neurologic manifestations of intravascular large B-cell lymphoma. Neurol Clin Pract. 2016;6(1):55–60. doi: 10.1212/ CPJ.0000000000000185

- Ponzoni M, Campo E, Nakamura S. Intravascular large B-cell lymphoma: a chameleon with multiple faces and many masks. Blood. 2018;132(15):1561– 1567. doi: 10.1182/blood-2017-04-737445

- Panda AK, Malik S. CNS intravascular lymphoma: an underappreciated cause of rapidly progressive dementia. BMJ Case Rep. 2014;2014:bcr2014203772. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2014- 203772

- Montori VM, St Louis EK, Habermann TM. 62-year-old woman with rapidly evolving dementia. Mayo Clin Proc. 2000;75(11):1193–1196. doi: 10.4065/75.11.1193

- Ponzoni M, Ferreri AJ, Campo E, et al. Definition, diagnosis, and management of intravascular large B-cell lymphoma: proposals and perspectives from an international consensus meeting. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(21):3168–3173. doi: 10.1200/ JCO.2006.08.2313