Hip Dysplasia

Hip dysplasia, also known as developmental dislocation or congenital dislocation of the hip, is where socket of the hip joint doesn’t fully support the ball of the joint. The condition can create a gradual misalignment or dislocation of the hip, which can wear down cartilage and lead to early-onset osteoarthritis of the hip. A dysplastic hip can also lead to an acetabular labral tear (a torn labrum, which is a soft tissue that lines and secures the hip joint socket).

Symptoms of hip dysplasia include pain in the groin and/or on the side or back of the hip joint. These symptoms can be distinguished from "growing pains," which are most common in kids under 10. Growing pains in the legs, knees and hips are usually felt at night, after the child has been active during the day, but then go away by the next morning. In a more serious condition like hip dysplasia, the pain will remain constant or increase over time. A child or young adult with hip dysplasia may also hear a sound – usually characterized as clicking, snapping or popping – when moving the hip during activity. The patient may also develop a limp to avoid the pain.

Anatomy of the Hip Joint

To understand hip replacement, you need to understand the structure of the hip joint. The hip is a ball-and-socket joint. The ball, at the top of your femur (thighbone) is called the femoral head. The socket, called the acetabulum, is a part of your pelvis. The ball moves in the socket, allowing your leg to rotate and move forward, backward and sideways.

In a healthy hip, soft tissue called cartilage covers the ball and the socket to help them glide together smoothly. If this cartilage wears down or gets damaged, the bones scrape together and become rough. This causes pain and can make it difficult to walk.

There is a wide range of severity among hip dysplasia cases. Milder cases may not be noticed until adolescence or young adulthood. More severe cases can usually be detected during the perinatal period (shortly before or after birth). There are several risk factors that increase the likelihood of hip dysplasia in a prenatal or newborn child. For children who have one or more of these risk factors, it is recommended that an ultrasound be performed at around four to six weeks of age to see whether or not the hip is developing normally.

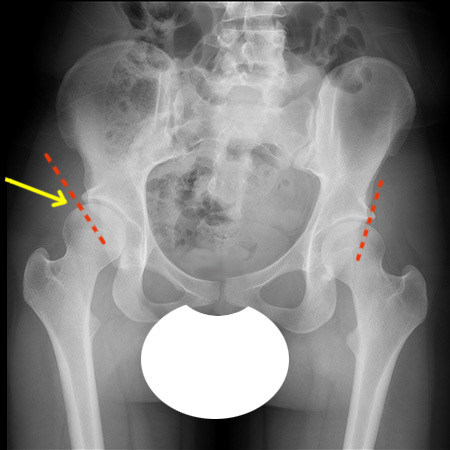

Anterior to posterior (front to back) X-ray showing hip dysplasia in the right hip (at the yellow arrow).

The dotted red lines illustrate the lack of acetabular coverage in the dysplastic hip vs. the healthy hip.

Treatments for Hip Dysplasia

People with hip dysplasia don’t always need surgery. If the condition is diagnosed early (in the prenatal period or during infancy) it can often be treated effectively with bracing. A mild hip dysplasia may not require any treatment, but may need to be monitored as the child grows. In such cases, complications may never arise or they may arise only once the child becomes an adolescent or young adult.

For more serious cases, hip dysplasia in a skeletally immature child can be treated with a variety different surgical procedures of the pelvis and acetabulum. In a skeletally mature teenager or young adult, a procedure called periacetabular osteotomy (PAO) is done. In a PAO, portions of the pelvis are cut in order to reposition the acetabulum so that it gives better coverage to the femoral head. This surgery has great potential to prevent or delay hip arthritis, especially if it is performed prior to irreversible cartilage injury, such as a torn labrum.

For more information, read the articles on hip dysplasia below. If your child or teenager has hip pain, you may also wish to visit our page, Hip Pain in Teens and Children – Q & A.

Articles on hip dysplasia

Articles on treatments for hip dysplasia

Hip Dysplasia Success Stories