The Emotional Impact of the Pain Experience

Adapted from a presentation at the SLE Workshop at Hospital for Special Surgery

The experience of pain

Many factors influence the experience of pain, which may be different for everyone. The pain experience may be a very personal one but it can also be impacted by larger societal factors. Some of the factors that can affect this experience are:

- age

- gender

- culture

- ethnicity

- spiritual beliefs

- life before pain onset

- emotional response

- medical care experience

- support systems

- access to care

- social determinants of health

- health disparities

Another factor may be a learned response related to particular, prior responses by your family members. Parents, for example, may respond to a child’s pain in a certain manner. This can set a foundational pain response for the child that may influence their responses in future pain experiences. Also, societal and medical care systems can impact the pain experience. For example, you may not have access to the care of a physician who is an expert in managing pain.

Additionally, changes in functioning, role (societal, social, or family), daily routines, job status, and sleep disturbance may contribute to chronic pain. These factors can cause distress which may also increase pain.

Individuals who experience chronic pain may find themselves feeling depressed or anxious. They will also be at risk for substance abuse and other mental health disorders. Other common emotional responses to pain can include sadness, frustration, anger or feeling misunderstood and demoralized.

It is important to recognize and monitor the emotional responses that frequently occur in your life as a result of having chronic pain. If you find that these responses are consistently affecting your mood or ability to function, you should talk with your primary care doctor or ask for a referral to a pain specialist. It may also be useful to seek help from a mental health professional such as a social worker. Another option available is a mental health hotline that can be contacted at 1-800-662-HELP, a confidential and multilingual crisis intervention service that is accessible 24/7. Additionally, you can contact The National Suicide Prevention Hotline at 1-800-273-TALK.

Emotions and the chronic pain cycle

Pain is influenced by emotions, and the cycle of pain and emotions are interrelated. Emotions may directly impact physical changes as well. For example, when you are anxious or angry, your muscles may tighten and that physical change may contribute to increased pain. Another challenge may be that patients might feel stigmatized when they demonstrate intense emotions like these in the context of their treatment.

Believing that you have control over your life and can continue to function despite the pain or subsequent life changes is something many people find can improve their mood.

Impact of pain on identity

How you identify yourself to others is an important element of your individuality. Having chronic pain and not knowing if or when it may go away can impact parts of your identity such as your self-efficacy and self-worth.

If you are experiencing chronic pain, you might not be able to complete certain tasks. In addition, you may find it challenging to fulfill certain roles that were an important part of your identity, and that can feel disempowering.

Where and how people derive value in their identity is culturally informed by social identity groups, including gender, ethnicity, and socioeconomic status. Depending on what roles or qualities you most value in yourself, you may have a more intense emotional response to challenges in some areas rather than others.

For example, someone who feels culturally that physical strength and ability is highly valued may feel the impact of the pain experience more significantly if it impairs this ability and they can no longer complete the same physical tasks.

Similarly, the “invisibility” of chronic pain can be isolating, especially in cases when a person’s outward appearance remains the same.

Impact of pain on family

As you experience pain symptoms, either acute or chronic, this can shift family dynamics. For example, a parent might not be able to fulfill certain roles that they were once able to, and communication between family members may change based on one member not wanting to “bother” the affected member.

Other factors that can impact the family system are increased stress, financial burden, effects on sexuality and other intimate relationships, and potential resentment within relationships. For the family members of people affected by chronic pain, a goal is to strike a balance between validating the individual’s pain and experience while also helping them to navigate life with this new challenge.

Impact of the treatment of pain on the patient experience

When patients’ pain does not respond to certain treatments or interventions, they may seem like symptom magnifiers and complainers. As a result, patients may feel demoralized or feel they are not being heard or taken seriously, which can in turn increase patient distress.

A study of patients with chronic pain found that they had a negative perception of support from their healthcare provider. They also reported a negative perception of their providers being open to discuss their chronic pain symptoms.1

There is an added layer of complexity among people of color and their emotional experience with chronic pain. Minorities who experience and seek treatment for chronic pain are often met with implicit bias and negative stereotypes. For example, there is a stereotype that exists that Black patients can tolerate more physical pain than white patients. Research has suggested that compared to their White peers, Black patients are undertreated and their pain is underestimated.2

The emotions felt by Black patients who experience chronic pain may be impacted by past experiences of unconscious bias and the presence of systemic undertreatment. A study of low-income Black patients found that when treating Black patients in an outpatient clinic, frustration was expressed by the doctors and the patients. This frustration often leads to a poor patient-physician relationship and poor management of their patients’ chronic pain.3

Communicating with your doctor

It’s hard for many providers to understand your pain, so it is important to advocate for yourself and to be as descriptive as possible. Your description can include things such as its frequency, triggers and intensity as well as what makes it better or worse. Keeping a home journal may help you to be more descriptive, accurate, and increase recall, since pain experience may be different on each day.

In many situations, people may find that it is helpful to receive a second opinion from another provider. If you do not feel you are receiving adequate support to help with your chronic pain, there are providers who specialize in pain management.

It is important to be proactive in seeking out:

- resources from your doctor or other health professionals

- support to help you cope with your pain

- effective methods to acknowledge your feelings and communicate them to others

To help your provider have a better understanding of your pain, become more familiar with common pain scales. Familiarity with these scales and anticipating the way pain is measured medically may help communicate this very personal experience in the most objective way.

Common pain assessment tools

Brief Pain Inventory (BPI)

The BPI measures both the intensity of pain and the interference of pain in the patient's life. It also asks the patient about pain relief, pain quality, and patient perception of the cause of pain. BPI is based on scales:

- “0” represents “no pain” and “10” represents “pain as bad as you can imagine”

- “0” represents “does not interfere” and “10” represents “completely interferes”

Wong-Baker Faces Pain Scale

This scale, which goes from Level 0 to 10, asks the person in pain to choose from a series of faces that best indicate the level of pain he or she is experiencing.

Level 0 is a happy face, indicated as “No Hurt”, and the scale goes up to Level 10, which is a sad/pained face with tears, indicated as “Hurts Worst.” Learn more and see a visual example at the Wong-Baker Faces Foundation.

Numeric Verbal Faces Pain Scales

This scale also uses facial pictures and a rating scale of 0 to 10. Level “0” is “No Pain,” while Level “10” is “Pain as Bad as It Could Be.”

Describing pain experience

What is pain? Other commonly used terms: Aches, soreness, discomfort.

Be descriptive: Include location, timing, and intensity. Using descriptive words will help the medical team be more informed about the type of pain, where its roots are, etc. Examples: Burning, aching, stabbing, piercing, throbbing.

Unhelpful pain beliefs and ways to address them

According to research, the way a person copes with pain affects the way they adapt to pain. Having to experience chronic pain causes a person to develop coping mechanisms in an effort to assist with managing or reducing their pain. In other words, some coping and adaptive mechanisms used by those with chronic pain may not be the most physically or psychologically beneficial. In fact, some coping mechanisms can cause an increase in pain.4 Therefore, it is important to be aware of your responses to your pain and how you cope.

Examples of unhelpful beliefs as related to pain are:

- Catastrophizing: Negative reactions towards actual or anticipated pain experiences that can include magnifying, ruminating and helplessness. Patients with chronic pain often have a difficult time adapting to their pain and there is often an increase in stress, anxiety, depression and sometimes thoughts of suicide.4

- Pain is sign of damage. (In cases of acute injury, it may be. In chronic disease, however, it is an unfortunate but non-damaging symptom.)

- Pain means activity should be avoided.

- Pain leads to disability.

- Pain is uncontrollable.

- Pain is permanent.

- All or nothing thinking.

Maintaining a sense of control over your life and believing you can continue to function, despite the pain, can have a positive effect on your quality of life. Finding more resources to learn more about chronic pain and coping strategies that may work for you may help you feel more empowered. They can include patient education about how to live with pain, communicating with your doctor about your concerns and challenges, discussing if pain is a sign of damage or whether activity can be continued based on tolerance.

Spirituality and coping with pain

Many people find that aspects of their spirituality help them to cope with their pain. Studies have suggested that spiritual belief can lessen the impact of pain-related stressors, improve pain tolerance and lower pain intensity.5 It is important for providers to understand how you cope with your pain holistically. Therefore, it may be helpful to share if components of your spirituality are helpful to your pain experience.

Spirituality was defined in one study as the extent to which a person has or is looking for a purpose or meaning in life, as feelings of connectedness to a higher power, and a source of hope in the face of adversities. The use of prayer has been shown to enhance pain tolerance and help patients think about pain differently.5

Mind-body techniques and other interventions

Mind-body therapies are techniques that aim to change a person’s mental or emotional state or interventions that use physical activity to help you relax. It includes cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), relaxation strategies, meditation, guided imagery and exercises such as yoga or tai chi.6

Relaxation techniques and meditation

Relaxation techniques have a variety of benefits that help with pain tolerance. Some of these benefits include reducing inflammation, causing muscle relaxation and enhancing a person’s mood. Examples of relaxation techniques are breathing exercises, massage, art and music therapy.6

Mindful meditation, shown to help decrease stress and pain, involves focusing the mind on increasing awareness of the present moment. This method to help cope with pain can be easily done anywhere, even on the bus.

An example of mindful meditation would be to sit up straight, close your eyes, and put aside all thoughts of the future and past. Staying present, the focus of awareness remains on your breathing.

This exercise could be done for just a couple of minutes, letting your thoughts come and go while being aware of your current state. It can be most helpful during stressful times such as holidays or during difficult life events. View our PDF, The Power of The Breath: The Mind-Body Connection Tips for Coping with Pain and Stress, to learn about how mindful breathing can help you cope with pain and stress.

Taking a few minutes in the day to practice mindful meditation can be beneficial. Through performing this kind of exercise, you can create a sense of control, which is crucial in making your pain experience more manageable.

Another helpful technique is guided imagery. This technique takes the focus off of your pain and instead focuses on a therapeutic mental image existing in the absence of your pain. In a review of nine clinical trials, eight implied that guided imagery helps to significantly reduce musculoskeletal pain.6 Learn more about how guided imagery can be used to help heal the body:

Some studies have shown that certain exercises such as yoga and tai chi may also be helpful. The positive effects of exercises such as yoga on chronic pain can be attributed to the emphasis it places on acceptance, meditation and relaxation.

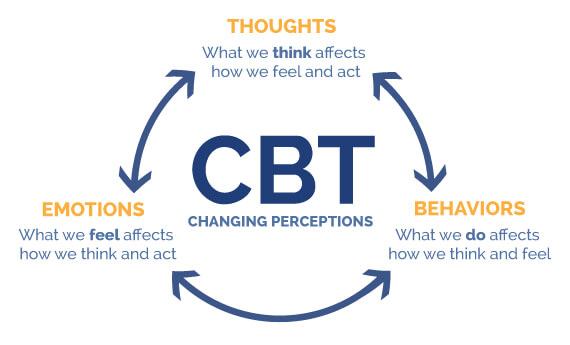

Cognitive behavioral therapy

CBT is an evidenced based therapy model that aims to change your negative thought patterns, which can result in a change in your behavior, which will in turn have an effect on your feelings or emotions.

A pain management program comprised of individuals living with chronic pain, found that depression decreased in participants that participated in a CBT treatment program. Individuals that experience chronic pain can learn techniques that will help manage their pain.7

Illustration by UTHealth Houston McGovern Medical School

Most importantly, the impact of pain is an entirely individual experience.

Patient resources

Below are some helpful books and websites that may enhance knowledge and understanding of coping with pain. These resources change continually and are designed for general education purposes. For specific guidance, please consult with your provider.

Books

- Catalano, E. M., & Tupper, S. P. (1996). The Chronic Pain Control Workbook: A Step-By-Step Guide for Coping with and Overcoming Pain (New Harbinger Workbooks) (2nd ed.). New Harbinger Pubns Inc.

- Davis, M. (2019). The Relaxation and Stress Reduction Workbook (A New Harbinger Self-Help Workbook) (7th ed.). New Harbinger Publications.

Websites

- American Chronic Pain Association

- PainEDU.org

- Pain Management patient education from HSS

- US Pain Foundation

References

- Jonsdottir, T., Gunnarsdottir, S., Oskarsson, G. K., & Jonsdottir, H. (2016). Patients’ Perception of Chronic-Pain-Related Patient–Provider Communication in Relation to Sociodemographic and Pain-Related Variables: A Cross-Sectional Nationwide Study. Pain Management Nursing, 17(5), 322–332. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmn.2016.07.001

- Hoffman, K. M., Trawalter, S., Axt, J. R., & Oliver, M. N. (2016). Racial bias in pain assessment and treatment recommendations, and false beliefs about biological differences between blacks and whites. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 113(16), 4296–4301. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1516047113

- Henry, S. G., & Eggly, S. (2013). The Effect of Discussing Pain on Patient-Physician Communication in a Low-Income, Black, Primary Care Patient Population. The Journal of Pain, 14(7), 759–766. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpain.2013.02.004

- Noyman-Veksler, G., Lerman, S. F., Joiner, T. E., Brill, S., Rudich, Z., Shalev, H., & Shahar, G. (2017). Role of Pain-Based Catastrophizing in Pain, Disability, Distress, and Suicidal Ideation. Psychiatry, 80(2), 155–170. https://doi.org/10.1080/00332747.2016.1230984

- Ferreira-Valente, A., Damião, C., Pais-Ribeiro, J., & Jensen, M. P. (2019). The Role of Spirituality in Pain, Function, and Coping in Individuals with Chronic Pain. Pain Medicine, 21(3), 448–457. https://doi.org/10.1093/pm/pnz092

- Hassed, C. (2013). Mind-body therapies. Australian Family Physician, 42(1/2), 112–117.

- Ólason, M., Andrason, R. H., Jónsdóttir, I. H., Kristbergsdóttir, H., & Jensen, M. P. (2017). Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Depression and Anxiety in an Interdisciplinary Rehabilitation Program for Chronic Pain: a Randomized Controlled Trial with a 3-Year Follow-up. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 25(1), 55–66. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12529-017-9690-z

Updated: 4/19/2022

Authors

Nadia Murphy, LCSW

Manager, VOICES 60+

HSS Department of Social Work Programs